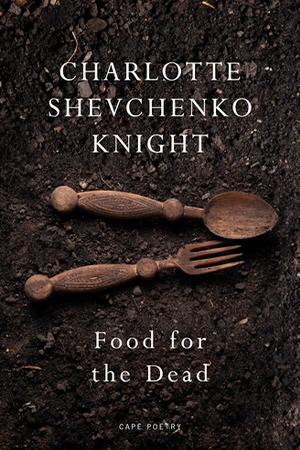

Food for the Dead by Charlotte Shevchenko Knight

London. Jonathan Cape. 2024. 64 pages.

London. Jonathan Cape. 2024. 64 pages.

A poet of both British and Ukrainian heritage, Charlotte Shevchenko Knight possesses the ability and insight to write poems about Russia’s brutal aggression in Ukraine in a way that few poets could. In her collection Food for the Dead, the Holodomor—the 1932–33 famine-genocide in which millions of Ukrainians starved due to Soviet policies—serves as the collection’s nucleus, around which family, generational trauma, and literal and figurative hunger revolve. Furious survival, both individual and familial, also takes center stage, and a fearless narrator reconciles not only with the emotional and psychological residue of their family’s traumatic history but also the reopening of inherited wounds by a present-day war that mirrors past ones all too familiarly. Readers travel through Ukraine’s history—from the Second World War to Chornobyl and into modern-day Ukraine where “the war . . . once again breaks out” and “babusi stand on their balconies / fists of tomatoes at the ready.”

In Shevchenko Knight’s poems, the “babusi” (grandmothers) are veritable forces entirely their own. In “A Gathering of Lozhky,” an attentive speaker gathers the babusi “as spoons” because they are “what keeps the dead feeding.” “Peonies on the Ground” offers readers a tender moment as a speaker lovingly practices the English language with “babusya inna,” who pronounces the word peony “with an O / like a cat’s yawn.” Other poems, like “Etymology,” portray the grandmothers like an ancestral, spiritual force who gather “for the words of a country / not a borderland.” The babusi’s presence throughout Food for the Dead is a testament to female Ukrainian fortitude, not only in the homeland but also in the diaspora.

“Radiant Summers” is beautifully direct in its acknowledgment about how Ukraine’s disasters define it for those who are unfamiliar with Ukraine’s traditions, culture, and diversity. The poem addresses an even larger issue Ukrainians have historically faced: an assumption about their identity based on historical events. The speaker reflects: “i think of her when i introduce / myself as ukrainian & am met with ‘oh—chornobyl!’” The speaker adeptly communicates that the word disaster defines “a country a time a girl,” that the word disaster means “‘unavoidable,’ ‘the will of god,’ a nuclear immaculate / conception.” The word nuclear alludes to the Chornobyl nuclear disaster, which, for many is the only anecdote of Ukrainian history they know. To reinforce the environmental and physiological consequences of the Chornobyl disaster, the speaker incorporates words like tumour and stinging as well as hyphenated words like white-hot. Phrases like “pure panic” capture the disaster’s continued legacy as well as the disaster’s initial chaotic aftermath.

“[untitled]” dares to tackle the ongoing politicization of language in Russo-Ukrainian relations. In the epigraph from 1863, Russian writer and politician Pyotr Valuyev states: “The Ukrainian language never existed, does not exist and shall never exist.” The epigraph establishes—particularly for readers unfamiliar with Russia’s historical oppression of Ukrainian language and culture—a historical context and rhetoric that Vladimir Putin has used to fuel propaganda espousing the Ukrainian oppression of the Russian language. Shevchenko Knight’s poem delicately manages the subject:

one tongue eclipses another

& it is almost romantic

to an outsider

viewing behind glass.

The lack of capitalization throughout the poem mimics the separation many readers have from the historical oppression by Russia experienced by Ukrainians. As the poem continues, the speaker employs words like erasure, which they perceive “as natural as the closing sun” to outsiders. However, the poem becomes more immediate when the speaker embraces the usage of a collective “we”:

we do not have the words

to tell of our suffering

unless we use the words

given to us by that suffering.

The “we” acts to unify the Ukrainian people, and the repetition of the word suffering reiterates the generational trauma and hurt experienced by Ukrainians, even in the diaspora. As the poem concludes, “language twitches / like wings pinned to a board.” The metaphor of an insect pinned to a board effectively portrays language’s fragility, and as the speaker reflects that the language exists “at the mercy / of a needle & thumb,” the speaker also reminds readers that language, like tradition, requires careful preservation.

Rife with anguish yet a stalwart generational song against totalitarianism and oppression, Charlotte Shevchenko Knight’s Food for the Dead introduces readers to a new generation of powerful and vocal Ukrainian diaspora poets. In Shevchenko Knight’s verses, time and space collide, and one generation’s stories influence and reshape another’s. History comes alive, and Shevchenko Knight evokes a Ukraine and a people cloaked in horror and beauty but not defined by the violence and brutality ravaging it.

Nicole Yurcaba

Southern New Hampshire University