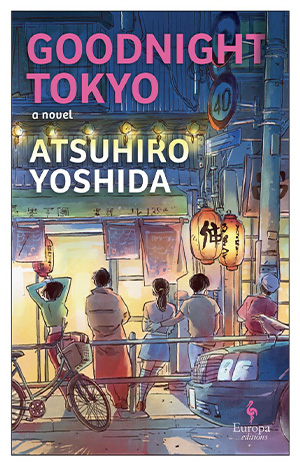

Goodnight Tokyo by Atsuhiro Yoshida

New York. Europa Editions. 2024. 176 pages.

New York. Europa Editions. 2024. 176 pages.

During the early-morning hours dominated by night-shift workers and by the eccentric and romantic few whose internal clocks simply skew nocturnal, a city as large and densely populated as Tokyo can seem almost small.

People in this city passed each other by in far more places and on far more occasions than they realized. For instance, they might come to within a block of a relative or close acquaintance during some random outing. They just didn’t know it. Even if they were to pass each other at close range on the same street, they would likely be forever oblivious to that fact. There were simply too many people around, too many other faces in the crowd.

But at night, this sense of missed connections shifts. With fewer faces wandering the streets, the faces that are there become familiar and known to one another. Such is the premise of Atsuhiro Yoshida’s Goodnight Tokyo. Written as a serial short-story collection containing twelve interconnected stories, Yoshida zooms in on the quiet characters who inhabit the early-morning hours of Tokyo, deftly weaving the ways in which their lives intersect.

The theme of intersection is far from subtle. One of the most prominent physical spaces in the book is a diner named Yotsukado, meaning “crossroads,” named as such based on its location at a four-way intersection. The proprietors of the diner themselves represent a crossroads: four women who separately owned diners but found themselves at a point of convergence: “While they weren’t particularly close, they would say hello whenever they bumped into each other. Those brief greetings gradually developed into longer conversations, until before they knew it, they learned that each had their own eatery and that they were all facing the same difficult business conditions.” The four women are introduced as a single entity through large blocks of untagged dialogue that eventually melt away to focus on the particular plight of Ayano, who remains fixated on the loss of her old diner and who pines for a patron who used to visit her there, a plotline among many that is further developed through the eyes and actions of other characters.

Yoshida patiently introduces his characters with effective restraint, introducing no more than two or three characters in each story, nearly all of whom return in interactions with other characters to surprising and satisfying effect. It’s a quirky cast that creates a sense of whimsy and real-life magic: a “procurer” for a large film company; a nighttime taxi driver; a call center operator; a detective, former musician, and son of a largely forgotten actor; a secondhand shop owner who maintains the pet theory that “when manmade objects were broken, they were reborn as something else”; a disposer of landline telephones; a country girl turned actress. Even less prominent characters, such as those who lack dedicated chapters and who could have easily been brushed off as set dressing, return repeatedly, offering glimpses into their own dynamism and showing how disparate communities have shifting and shared memberships.

Through the intersections of seemingly unrelated characters’ lives, Yoshida explores the idea of fate as the connectivity between people. He builds an intricate tapestry of connectedness that serves as a gentle reminder that sometimes the stranger you run into is actually a friend of a friend or knows your family or is otherwise connected to you in ways you may never know. These fated connections, combined with the somber, yearning mood of his writing, create the effect of teetering along the edge between surrealism and the absurd reality of a major city’s early-morning hours before the majority wakes, those still-dark hours where the sleep-deprived and nocturnal define their own realities and norms. At times, his characters are even unsure what is real or imagined. It is this sense of unreality that fosters the deepest connections. In a particularly moving scene, Ayano, who mistakenly believes she is dreaming, makes a confession to a stranger: “Why was she pouring her heart out to a complete stranger like this? . . . Perhaps it was discovering the hidden strength of her desire that blew her characteristic hesitation to the wind.”

At its simplest, Yoshida’s Goodnight Tokyo is a gorgeous and playful portrait of a city at night. By constraining this portrait to the hours between 1 a.m. and 4:30 a.m. over several nights, he creates a foundation for intimacy, showing both the ways in which lives become more aware of one another when there are fewer around and also how an interpersonal openness develops when operating outside of routine. In many ways, Yoshida’s English-language debut feels like people-watching; it’s a window into observing the ways we’re all connected, even when beyond our knowing.

Lauren Bo

St. Louis