“Between the Facts”: A Conversation with Monique Truong

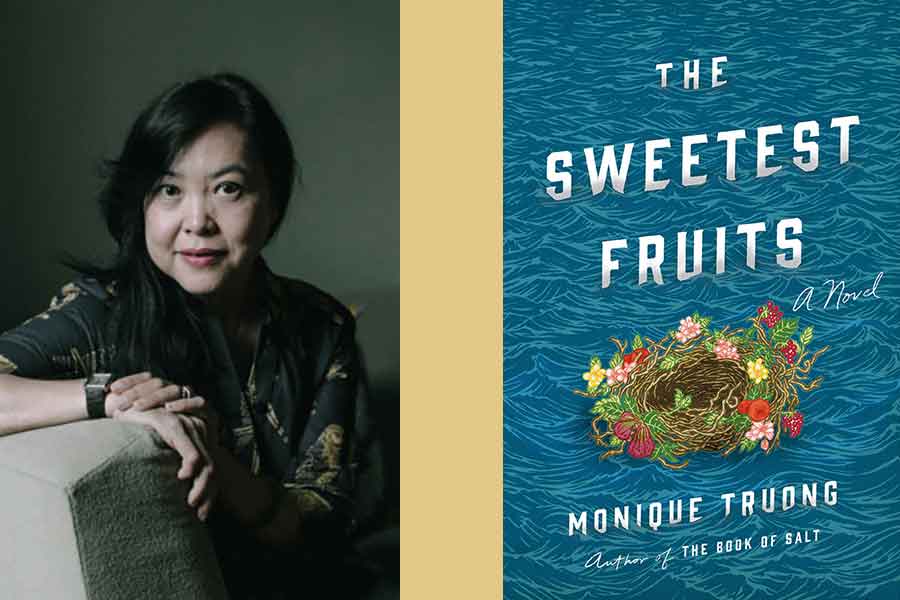

Monique Truong, who came to the United States in 1975 as a refugee from Vietnam, began exploring untold and ignored histories in her first novel, The Book of Salt (2003), told through the voice of Binh, the cook of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in Paris. Her autobiographical second novel, Bitter in the Mouth (2010) is a coming-of-age story set in North Carolina. In her most recent novel, The Sweetest Fruits (Viking, 2019), Truong tells the story of Lafcadio Hearn from the perspective of three women: his mother, Rosa; his first wife, Alethea; and his Japanese wife, Setsu.

Shea: At its core, The Sweetest Fruits is a story about storytelling—and it’s Russian dolls of narrative! It’s not only that three different women have their say about Hearn and their relationship with him, but each is telling her story to a specific audience—so issues of mediation and agency add further complications, as do oral vs. written stories and translation. How did you arrive at this approach instead of just telling the story in the voice of one person, then the next, then the next?

Truong: This question is a Russian doll of inquiries! You’re absolutely right that the novel is interested in the different ways that stories are transmitted to us: oral vs. written, in our mother tongue vs. in translation, private story vs. public history, women’s voices vs. men’s, face-to-face vs. secondhand, in the present vs. memory.

For me, the writing process always begins with the narrator’s voice. I’ve chosen the first-person voice for all three novels, because language to me shapes and informs the character. The vocabulary, syntax, quirks, repetitions—all play a role in helping me think about a character.

Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904) and the Great Literary Men of his era, as well as those who preceded and followed him, were positioned as experts, and the world and its people had to filter through them in order to matter and be documented. These men possessed the authority and the authoritative voice. I wanted to counter that tradition. So, it made sense to me to open up and share the narration among the three women (four when you count the excerpts by Hearn’s first biographer, Elizabeth Bisland), which serve as the framework of the novel. The voices each take the mic, as it were, in ways that are specific to their circumstances and their access or lack of access to the written word. They also take that mic for differing reasons. In life, we don’t just open our mouths or put pen to paper to share our stories for no reason whatsoever, yes? There’s always a motive, and Rosa, Alethea, Setsu, and Elizabeth’s motives become as much a part of their stories as Hearn’s.

The Great Literary Men of Hearn’s era, as well as those who preceded and followed him, were positioned as experts, and the world and its people had to filter through them in order to matter and be documented. I wanted to counter that tradition.

Shea: To what extent does this emphasis on storytelling address what you’ve called your “distrust of history”? It’s integral to this novel but also front and center in The Book of Salt, your first novel.

Truong: Looking at the long arc of History, with a capital H, it is, in fact, the history of men, their deeds, their thoughts, their actions. With rare exceptions, women were excluded from the production of History and from its content. So of course, I distrust it. Or rather, I look at it for what it is: a partial History.

Looking at American history, until the end of the Civil War, access to the written word was denied under the laws of this country to enslaved people. As we know, this denial lasted much longer under Jim Crow and other discriminatory practices that sought to segregate the races and deny opportunities for education to African Americans. Separate but equal was a fallacy and an insult. So, also with rare exceptions, American History was written by men who were white. It’s an even more partial History. Why should I—or any of us—place our trust in it?

The challenge, for historians and for historical novelists as well, is that there’s a lack in the archives when we strive to include the stories of women and people of color. The correspondence, the journals, the published books—the direct documentation by these subjects of their thoughts, beliefs, and experiences—are nonexistent.

Though again, there are rare exceptions, one of them being The Bondwoman’s Narrative, an autobiographical novel by a formerly enslaved woman named Hannah Crafts, whose manuscript Henry Louis Gates Jr. had purchased at auction—ah, how “purchased at auction” takes on such weight and ironic resonance here—edited, and published in 2002. This novel was important to me as I began the process of imagining Alethea’s voice.

But as I was saying, the archive is more often empty. These subjects—women (not of the privileged class, who were the rare exceptions of whom I speak) and people of color—appear as footnotes, minor figures, the wives, mistresses, servants, and property of the Great Men, who wrote about them in passing.

Shea: The opening epigraph of the novel, by Emily Dickinson—“tell all the truth but tell it slant”—seems perfect. Yet as I think of the three women central to Hearn’s life, I wonder if another fitting inspiration is Faulkner’s “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Truong: I agree that the past is never dead—because what is the past but the current age’s understanding of the facts: our characterization, our summation of what has taken place? Given my understanding that what we know about the American past is partial and missing more than half of those who were present, then the past is roiling with voices that are still waiting to be heard.

Given that what we know about the American past is partial and missing more than half of those who were present, then the past is roiling with voices that are still waiting to be heard.

The territory in which I work as an author of historical fiction is between the facts. Rarely, if ever, would I change a date or a place, but if there’s a blank—a silence that the historians cannot fill—between their facts, then I get to work. This territory that I speak of is vast and is where the stories of women and people of color are found.

Shea: You’ve said that you discovered Hearn through the cookbook written during his time in New Orleans. But what clues did you have about Rosa and Alethea?

Truong: Neither Rosa nor Alethea had access to the written word, which I think of as an important reframing or rephrasing of what it means to be “illiterate.” These women didn’t know how to read or write because they were denied the right and the opportunity to learn. To be “illiterate” is the result, while “did not have access” takes into account the denial and imposed lack.

In my novel, as in life, Rosa and Alethea must tell their stories to a scribe, if they wished to be documented. Rosa’s scribe is a girl still in her late teens to whom Rosa dictates a letter, intended for Lafcadio, so when he’s older he would know why his mother had left him at four years of age in Dublin to be raised by a distant relative. Alethea’s scribe is a young white woman reporter from the Cincinnati Enquirer who’s there to report on a literary scandal with local interest: that the famous, recently deceased writer Lafcadio Hearn, who began his career as a reporter in Cincinnati, had been married to a woman of color.

If I’d written this novel from Hearn’s point of view, there would be few interesting questions for you to ask about sources and how I found them. . . . But because I chose to write this novel in the voices of the women in his life, sources were scarce. I hope that readers will keep that scarcity in mind when they approach histories as well as historical fiction about women or people of color. In short, the authors who write such works did more work than their counterparts who focused on the lives of white men.

For Rosa, I didn’t want to rely solely on how she was characterized by Hearn’s biographers, as childish, impetuous, and a woman of questionable moral character, unschooled and illiterate. I stitched her voice together from the historical bits and pieces that I did find about the lives of women on the Ionian Islands during British rule, from cookbooks that focused on the food traditions and lore of the islands, from the Greek Orthodox churches that I’d visited on Lefkada—the imagery, smells, architecture—and, of course, the landscape of Lefkada. Rosa was born on the island of Kythira, the southernmost of the Ionian Islands, but given the break that came with her family I thought it plausible and likely that Lefkada became her truer home, the place where she became herself.

For Alethea, in addition to The Bondwoman’s Narrative and other sources, I relied primarily on two newspaper articles, each purporting to represent her voice. The first was a feature written by Hearn, published without a byline, when they were married in Cincinnati. Her name didn’t appear in the article either, but it’s clear among historians that it’s about her. In this feature, the reporter is seated on the steps of a boarding house, listening to the house’s cook who’s a gifted storyteller and who’s spinning eerie tales about “ghost people.” The reporter writes that he cannot do justice to her voice but then places quotation marks around almost the entirety of the story to indicate that the story is being told in her words.

The second article was an interview with Alethea and a reporter, also without a byline, that appeared in the Enquirer in 1906 with these headlines: “Claim . . . Made by a Negress” and “Ex-slave says she was married to gifted author.” The interview was chock-full of facts and details about their lives together as man and wife. Alethea’s voice wasn’t as present in the interview, but the woman was present, I thought, in what she chose to share with the reporter. I also thought about what Rosa may have said that was then ignored or edited out by the reporter.

Shea: I can’t help but ask about the details of the underwear: the silky lace ones, Hearn’s fastidiousness with his own? Did you make this up?

Truong: You would be odd if you didn’t ask this question, because there are a lot of undergarments in this novel!

The short answer is that undergarments are what we keep closest to our skin, meant only for our eyes and perhaps a beloved’s. They are what we can skimp on because no one will see them anyway or splurge on because it’s no else’s business but our own. As personal belongings go, they carry with them a surplus of meanings and metaphorical possibilities.

The longer answer is that in the 1906 Enquirer interview with Alethea, she shared that Hearn was very particular about his linens. That word can mean sheets and household cloths, and it can mean undergarments. It struck me as such a literally intimate detail to share about him, and I wondered why she would do so. Did Alethea need to keep the reporter’s interest? Was Alethea getting a bit of revenge? Or simply stating a fact in passing?

Alethea’s closest friend in the novel, Charlotte, is a washerwoman. What would catch her eye during the daily monotony of washing other people’s clothing but undergarments cut from silk and “bedecked” with lace? In the novel, it is this washerwoman who first warns Alethea about the fastidiousness of Hearn, but she ignores her friend’s warning and becomes his wife anyway.

Shea: During the time you were writing The Sweetest Fruits, you traveled extensively and for relatively long periods of time both in the United States and to Greece and Japan. How was this travel integral to your research and writing of the novel?

Truong: Thanks to a U.S.-Japan Creative Artists Fellowship, I was able to live and conduct research in Tokyo for three months, which honestly felt like a mere three weeks. There was so much to learn, and I was lost most of the time, spatially and otherwise. Though I’d attempted to learn some Japanese phrases and basic vocabulary prior to leaving NYC, I couldn’t read kanji characters or kana scripts. For three months, I no longer had access to the dominant written language, unless the signs or labels were also written in romaji (romanized Japanese). I was placed in a position of not knowing what Hearn had experienced during most of his fourteen years in Japan. He was never fluent in Japanese, and only toward the end of his life was he able to write simple, childlike letters to Setsu. Day-to-day life was disorienting, and it was liberating—the words around us that demand so much of our attention no longer had any effect. But, of course, so much of day-to-day life was impossible to manage without the assistance of a bilingual friend.

While in Tokyo, I thought often about Hearn’s dependency on Setsu. She could read and write in Japanese. She had the upper hand linguistically. Hearn’s biographers had emphasized instead her illiteracy in English, and how Hearn devised a private language for them, consisting of simple Japanese and English words. He was, in their eyes, the sole deviser of this private language, as opposed to the language being a co-creation, the domestic shorthand of a husband and a wife.

Shea: What was the most significant change that you made during your revision process with this novel? Where were the fault lines in your initial draft(s)?

Truong: At first, Rosa didn’t interact that much with her letter writer Elesa, directing toward her the occasional comments to establish that they are both on a ship and where they are headed to, etc. After the first full draft, I realized that Elesa had to become more of a character. After all, the listener—the specific listener to whom a story is being told—can have an effect on the storyteller and the story. Elesa, here the listener and also the scribe, is not an inanimate object but a person whose body language and facial expressions would signal to Rosa that she had gone too far or hadn’t said enough. Once I decided to expand Elesa’s story and Rosa’s engagement with her, Elesa became a stand-in for the young Rosa, a daughter who needed another woman to guide her through the maze of male-female relationships, for one thing. The ship that they are on becomes a classroom for female power and how to wield it. Rosa, therefore, is moved to speak far beyond the borders of what her son Lafcadio would need to know about her. There are those stories meant for Lafcadio and those for Elesa only, and Rosa parses them carefully.

Shea: Your fondness for Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu is clear throughout the novel– but I’m still not sure how you feel about Hearn himself. You admire much about him, you identify to some extent with his life as a continuous search for belonging, and yet you hardly paint him in a glowing light.

Truong: After spending eight years with the women in Hearn’s life, I think I’ve come to know him not as a Great Literary Man but as a man. I like that man much more. I’m more forgiving and tender toward him. I hope that readers will come to that Hearn as well.

I also have reassessed his literary legacy. I think of him now as an excellent observer, listener, and scribe. He was a man of letters, who, unlike so many men of his time, didn’t dismiss outright stories that were about or were told by those at the margins of society: for instance, the stories of women and women labor. He wrote stories about African Americans, from cooks to the dockworkers on the levees, and stories about other communities of color, including one of the few contemporary accounts of a settlement of Filipino fishermen in Louisiana. One of Hearn’s stronger essays, entitled “Les Blanchisseuses,” is about the washerwomen of St. Pierre, Martinique. Let’s be clear, however: these are also Hearn’s most racist and racially myopic pieces.

What happens when the person who prepares that “good” meal is demoralized, bone-tired, the object of racism and bigotry because of the color of their skin, their “accented” English, or their lack of fluency in the dominant language?

Shea: You have said that immigrants to the US tend to be “ravenous in a land of plenty.” Could you expand on what you mean by that description?

Truong: To have a good meal—a truly satisfying, sustaining meal that feeds body and spirit—I think means more than having the money to buy the foodstuff or pay for the restaurant bill. As immigrants to this land of opportunity—and once we become citizens of it as well—we focus our energy on acquiring the material, the economic achievements, the freedom to earn more for our family.

But what happens when the family and friends whom we want to gather around the table for that “good” meal are far away, cannot reach these shores because of restrictive immigration laws that deny immigrant families the hope of being reunited with one other? What happens when the person who prepares that “good” meal is demoralized, bone-tired, the object of racism and bigotry because of the color of their skin, their “accented” English, or their lack of fluency in the dominant language? What happens when that “good” meal is harvested using undocumented, exploited laborers? What happens when that “good” meal is prepared by food processors, restaurant workers, and food deliverers who are also undocumented and exploited? I ask these questions but I know the answer: we all end up hungry. Our stomach may be full of cheap, readily available food, but as a nation we are ravenous.

August 2019

Editorial note: Shea’s review of The Sweetest Fruits is forthcoming in the Autumn 2019 issue of WLT.