Being Black in America: In Conversation with James E. Cherry

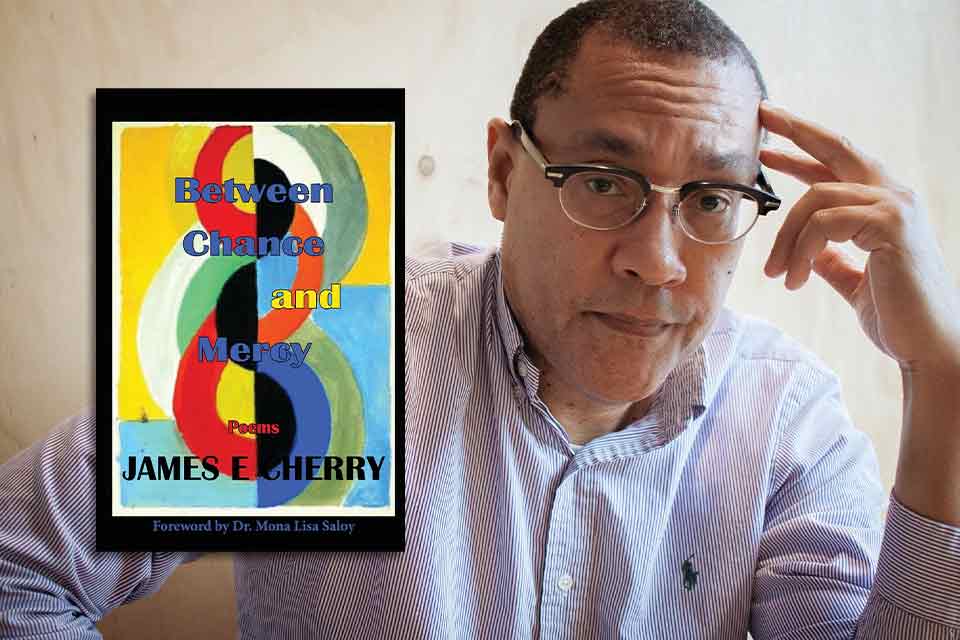

James Baldwin, whose hundredth birthday we recently celebrated, once declared that besides bearing witness to America’s perennial and intolerable abuse of its Black and colored citizens, his vision as an artist was to “build a table” on which people would “eat for a thousand years.” African Americans like James E. Cherry who grew up reading Baldwin were inspired by his gift of courage and truth-telling. Poet, fiction writer, essayist, social critic, and literary activist, Cherry is the author of the poetry collections Between Chance and Mercy, Honoring the Ancestors, and Loose Change. His fiction includes a collection of short stories, Still a Man, and two novels, Shadow of Light and Edge of the Wind. He has been nominated for an NAACP Image Award, a Lillian Smith Book Award, and has received fellowships from the Martha Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing and Kimbilio for Black Fiction.

James Baldwin, whose hundredth birthday we recently celebrated, once declared that besides bearing witness to America’s perennial and intolerable abuse of its Black and colored citizens, his vision as an artist was to “build a table” on which people would “eat for a thousand years.” African Americans like James E. Cherry who grew up reading Baldwin were inspired by his gift of courage and truth-telling. Poet, fiction writer, essayist, social critic, and literary activist, Cherry is the author of the poetry collections Between Chance and Mercy, Honoring the Ancestors, and Loose Change. His fiction includes a collection of short stories, Still a Man, and two novels, Shadow of Light and Edge of the Wind. He has been nominated for an NAACP Image Award, a Lillian Smith Book Award, and has received fellowships from the Martha Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing and Kimbilio for Black Fiction.

When I first read Between Chance and Mercy (Aquarius Press, 2024), I thought I heard Baldwin insisting that Black lives matter. Like Baldwin, Cherry does not preach to a deaf audience. He simply narrates and sings about personal and collective histories that humanize Black lives in America, a humanity so blatantly diminished by white supremacy. He does not want us to forget the contributions of generations of Black people to the development of America, so he writes poetry as a memorial of history, as a memory of truth. But what is America’s modernity if it thrives on acts of indefensible discrimination? Between Chance and Mercy compels readers to look through America’s cracked walls to see a nation so insouciantly racist it could not spare its own citizens. America has a white soul, as W. E. B. Du Bois tells us. A soul, nonetheless. Frederick Douglass reached out to the American soul when he asked the nation to remember the role its Black population played during the Civil War. “If this war is to be forgotten,” Douglass said, “I ask in the name of all things sacred, what shall men remember?” In Between Chance and Mercy, Cherry remembers the names and faces of those who make daily sacrifice for America’s unity.

Darlington: Between Chance and Mercy seems to be in conversation with Baldwin. I hear the inflections of his voice in the poem’s lamentation that America is still suffering from the problem of race, still blinded by the glitter of whiteness. Baldwin declared his charge against America three years before his demise. “What has happened in the time of my time,” he narrated, “is the record of my ancestors. No promise was kept with them, no promise was kept with me, nor can I counsel those coming after me, nor my global kinsmen, to believe a word uttered by my morally bankrupt and desperately dishonest countrymen.” I sometimes see myself among Baldwin’s “global kinsmen.” We have heard Baldwin’s account of being Black in America; what is your own story, James?

It’s a weary blues, to quote Langston Hughes. But it’s our blues.

James: As one of America’s preeminent thinkers, scholars, and intellectuals, Baldwin made an indelible impression on this nation and the world. As a Black writer, his voice will always resonate in my writing, whether I am aware of it or not. As one who comes after him, my account of being Black in America is that the name has changed, but the history remains the same. There has been progress, but it is merely cosmetic. The core issues that determine the quality of life for Black folk are still prevalent today as they were during Baldwin’s time and the time that proceeded him. I am speaking of the high levels of unemployment, voting rights, police misconduct, poverty, redlining, mass incarceration, and the rise of fascism. Due to systemic racism, Black people face these issues for their entire existence in America. It’s a weary blues, to quote Langston Hughes. But it’s our blues.

I totally understand Baldwin’s pessimism, but I’m not without hope, because I believe in the indomitable spirit of Black folk. Any other race would probably not have survived the conditions of this place. Despite our sufferings, we have made the world better with discoveries in science, medicine, technology, history, blues, and jazz. We were born to fight. We’ve been knocked down but have never learned to be comfortable on the ground. My story is part of the continuum of struggle, survival, and triumph. America is on the precipice of a totalitarian state. But, as Kendrick Lamar would say, we gon be alright.

America is on the precipice of a totalitarian state. But, as Kendrick Lamar would say, we gon be alright.

Darlington: The poems “Freedom” and “Prelude to an Ethnic Cleansing” remind me of the struggle to save the soul of America from reaching the stupefying height of internalized cruelty Du Bois associates with Europe. I’m glad you challenge the ideal of freedom that powered the American Civil War with the evidence of the “unmarked grave” of “black faces / armed with courage and Springfield rifles.” You live, write, and teach in Tennessee, the very place where the 61st Regiment was organized in June 1863. What relationships exist among place, race ,and history in your collection?

James: The first thing we ought to do is question the idea of America having a soul and, second, if 250 years of chattel slavery, as well as 100 years of de facto slavery, wasn’t the actual “stupefying height of internalized cruelty,” then what was? But to your question about place, race, and history, they’re inextricably linked. I’m a southerner, and whether I’m writing about the lynching of Eliza Woods that took place on the court square in Jackson, Tennessee, in 1886 or the forced removal of the Chickasaw Nation from this part of the country, place, race and history intersect and inform, and without all three, the narrative would not exist.

There are poems in the book about George Floyd, Mike Brown, and Eric Garner. These are American poems. And still today, the South gets a bad rap concerning race relations, past and present. But as Brother Malcolm said, everything below the Canadian border is south. The whole nation benefited from slavery and is complicit in the continuance of white supremacy. As a Black writer, it is incumbent upon me to address these themes in my work. But there are poems in the book about family and Covid. Writing from one’s culture creates a universal language that allows for insight and understanding of the human condition. Wherever there is pain or joy or suffering or heartbreak or hope, we are not alone.

As Brother Malcolm said, everything below the Canadian border is south. The whole nation benefited from slavery and is complicit in the continuance of white supremacy.

Darlington: Baldwin believed that the betrayal of Black people, which manifests in the refusal to acknowledge their contribution to the making of the United States, is America’s most unfortunate and unforgivable crime. His rage in The Fire Next Time makes me imagine the disappointment of Anderson Ruffin, Robert Smalls, Douglass, and other hopeful Black people who worked hard to ensure the inclusion of the 61st Regiment in the Union Army. Hear him: “the crime of which I accuse my country and countrymen, and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them is that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it.” More than sixty years after Baldwin’s utterance, you declare in “Freedom” that “freedom / is a broken shackle / rusting between rows / of Tennessee cotton.” And in another poem, “The Letter,” you describe the racially motivated incrimination and imprisonment of a boy, whose “height / complexion and hairstyle are lost / to a sifting past where all the remains / of our lives together are three short paragraphs / on State sponsored stationery.” Why has nothing changed about how America treats its Black population after all these years?

James: America, since its inception, does not recognize Black people as human beings. That’s the premise of our relationship with our own country, and when an organization calls themselves Black Lives Matter, that is because they realized that in America, Black lives have never mattered. The only love America has exhibited toward Black people has been through civil war or imposed by the court system, if you want to call that love. Black people have been taught to betray themselves by internalizing a false inferiority that manifests itself in self-hate. How else do you explain our desire to imitate the perversity of a dominant culture, engage in self-destructive behavior, or destroy one another?

When an organization calls themselves Black Lives Matter, that is because they realized that in America, Black lives have never mattered.

White people have not fared much better. Maybe worse. To sustain a false sense of superiority, you have to dehumanize and demonize another group of people to rationalize your own behavior. But at what cost? If past behavior is an indicator, I propose that most white people, even today, are not fully in touch with their humanity because they have betrayed that same humanity. Until this issue is resolved openly and honestly, the past will continue to be prologue. Every American institution—whether it is education, criminal justice, banking, housing—is built upon the foundation of white supremacy. That dictates the quality of life for Black people and cripples the nation as well. Even something as innocuous as sports hasn’t been exempt. Black quarterbacks are plentiful now, but not so very long ago they were thought to not have the acumen to be decision-makers.

Darlington: It seems to me that you think of yourself as an African in America. Is this a manifestation of the double consciousness Du Bois wrote so articulately about?

James: Within the next year or two, I plan on visiting the continent of Africa, and I wonder if I will be received as an African or as an American. Probably the latter. Africans have been in America long enough now, and judging by our behavior, it’s sometimes hard to distinguish the difference between the two. I’m a descendant of an African in America. My dilemma, and that of other Black folk in America, is which of the fifty-three countries in Africa are we descendant from. I wouldn’t attribute my worldview so much to a double consciousness, but I understand who I am and where I am because of the life and writings of Du Bois, Malcolm X, Baldwin, Fannie Lou Hamer, Angela Davis, Ida B. Wells, and others. The list is long and varied, and I return to their teachings often.

Darlington: Speaking of great influences, Between Chance and Mercy opens with “Cherry Cherry,” a poem Wanda Coleman wrote for you in 2013. In the poem, Coleman remembers the past with both passion and hesitation, because the present is forged out of the same stern unseasonal loss, and that makes the “rainy and sunny days” of her life simultaneously “drunk with sound.” Did Coleman publish this poem in her lifetime? And how did you feel when you received the gift?

James: It was a gift indeed! We never met personally but struck up an email correspondence during her illness. She had ceased writing during that time, and as a big fan of her work and her life, I tried to encourage her as best as I could. The poem arrived in my inbox one morning and moved me to tears. She never published it in her lifetime, but I had to do something with it and was honored to include it in my own collection. That’s not normally done, but it’s Wanda Coleman.

Darlington: Coleman added this postscript to the poem, “Dear Mr. James, This is the first poem I’ve written in a year since my world fell away. The credit is all yours. Thank you.” This was dated August 7, 2013. Coleman passed away three months later. I read Dan Chiasson’s tribute to Coleman with trepidation. It is a coherent and assured posthumous assessment of the almost neglected legacy of a poet of great suffering and greater talent. What could have fallen apart in the world of this unashamedly confessional artist?

James: It was a long, arduous illness. But her indomitable spirit and her unique perspective on what it means to be Black and female in this country live on. She was an American original and a poet’s poet. Her sonnets were innovative, and she just didn’t write poetry, she lived it. She is an ancestor now. But the work she left with us continues to influence, inform, and inspire me. Always will.

Darlington: Did anything or anyone in your childhood prepare you for this life of intellectual pursuit?

James: My great-great-grandfather was instrumental in Tent City. Tent City, also called Freedom Village, was an encampment outside of Memphis in Fayette County, Tennessee, for African Americans who were evicted from their homes and blacklisted from buying amenities as retaliation for registering to vote during the Civil Rights Movement. It began in 1959 and lasted about two years. My great-great, John Lewis, was an organizer in trying to relieve the suffering of those involved who were trying to survive in less than human conditions. His son, the Reverend U. D. Lewis, along with several other Baptist ministers, established a nursing facility, Mission Convalescent Home, in west Tennessee in 1964 for African Americans who were denied long-term care due to the color of their skin. That facility is still extant.

I was raised in a Black neighborhood in the 1970s that was transitioning from a working-class neighborhood to one struggling with unemployment and overall hopelessness. I’m not sure the idea of a “Black Community” exists anywhere today, but during those days, even with the changes the neighborhood was going through, there were people who encouraged me to reach beyond where I was, informed me about others who had, and chastised me when they thought I was not trying to be my best. And unlike a lot of childhood friends, I had a father in the house. James W. Cherry never chased fame or fortune, but simply stayed married to the same woman for over forty years, never abandoned his seven children, and rose every morning to punch a factory time clock to put food in their mouths. He was a reassuring presence and a role model without trying to be one. His example is a form of racial pride also. I carry the independent spirit and emotional toughness of all these men, and it has colored my intellect and worldview. If something needs to be done, make it happen.

One such example is that I consider myself a literary activist. I’ve had a modicum of success as a poet and wanted to give back. Therefore, I founded and am president of the Griot Collective of West Tennessee, a nonprofit poetry workshop where I mentor other Black poets and attract to the city poets of national acclaim. Frank X Walker, Mona Lisa Saloy, Randall Horton, Allison Joseph, Jacqueline Trimble, and Ama Codjoe have enriched the local community here. The same applies to jazz music, which is akin to creative writing and very dear to me. There was none on a consistent basis until I led the effort to bring bebop and Black music to the city. The Jazz Foundation of West Tennessee lives!