7 Questions for Iheoma Nwachukwu

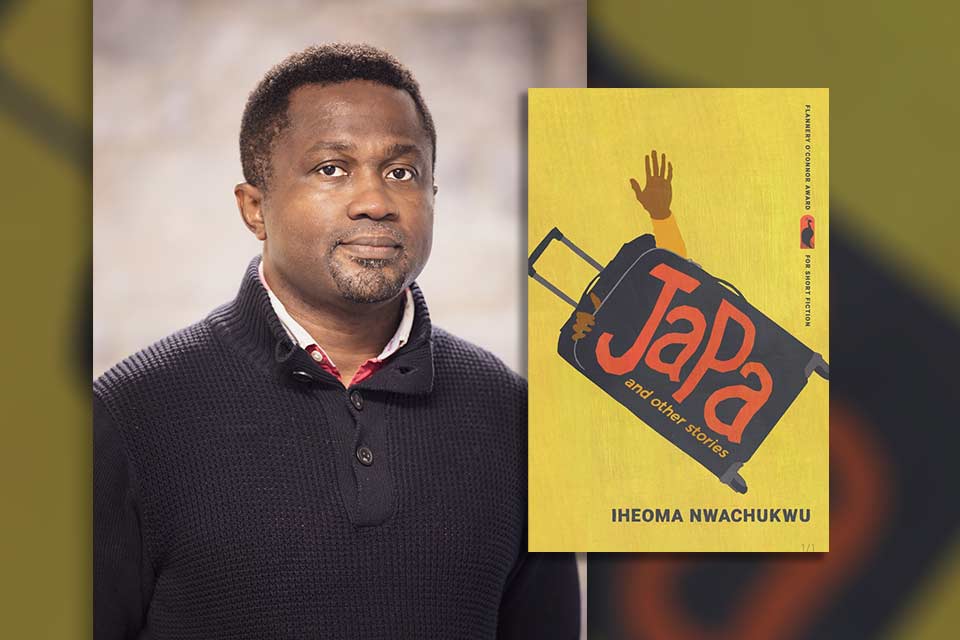

In September, the University of Georgia Press published Japa and Other Stories, Iheoma Nwachukwu’s debut collection of short fiction. In these eight stories, Nigerian immigrants trek through a desert, become temporary Mormons, and sneak through Russia as they seek new life in strange territories. The collection won the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction.

In September, the University of Georgia Press published Japa and Other Stories, Iheoma Nwachukwu’s debut collection of short fiction. In these eight stories, Nigerian immigrants trek through a desert, become temporary Mormons, and sneak through Russia as they seek new life in strange territories. The collection won the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction.

Q: Some readers may not be familiar with the term Japa, the book’s title. Could you talk a little about that?

A: Japa is a verb: to leave a place quickly. To emigrate. It’s an adjective: describing the person who’s emigrated—that japa dude. The word is actually Yoruba slang, whose literal translation is “rip an arm off.” A freeing movement so forceful your arm might come off. Because if people had a choice, they wouldn’t leave the familiarity of their homelands, the embrace of their friends, for some country that may, or may not, welcome them. So emigration is like jerking your arm out of the grip of poverty or insecurity, or terrorism, or civil war, to make meaning out of your life elsewhere.

Q: What inspired the stories in this collection?

A: I wanted to do something similar to what R. K. Narayan did in Malgudi Days. Imagine a world filled with the rich lives of connected people. Karan Maharajan pointed me to Narayan during our time at the Michener Center. And I fell in love with Narayan. He was an effortless storyteller. I used to think Malgudi was real. It would flatter me if readers thought Japa Town was real.

Q: You teach at Eastern University in St. David’s, Pennsylvania. Is there a piece of concrete advice you share with your short-fiction writing students that you could share here?

A: Describing landscape in fiction is legitimate because as a character yearns, they try to immerse themselves in the flora, the fauna, the walls of the market, the sky overhead. Landscape is a mirror in which characters try to see themselves.

Landscape is a mirror in which characters try to see themselves.

Q: You’ve worked as an ad exec, a kindergarten teacher, and a chess pro. How have these experiences influenced you as a writer?

A: Each job carried a different wavelength. With its routines, its difficulties, its demands. The ways in which they shaped identity. When I was an advert exec for instance, I wore a tie to work. You wouldn’t catch me passed out in a tie. As a chess pro I carried photocopies of chess problems in my pocket. Each job brought its own discipline, its own ways of looking at the sun. They are there in my faithful writing life, in my almost morbid interest in characterization. In the peripatetic nature of the fictional worlds I envision. These jobs have filled my life with music.

Q: What do the best stories do?

A: Without setting out to be didactic, the best stories teach you something useful about the nature of your existence. There’s always something at the center of such stories, an inexplicable “leaping out.” Allan Gurganus says a good story should leave you with a complexity of afterthought, and I agree.

Q: What in culture, outside of writing, has your attention at the moment?

A: Soccer and music. The Victor Osimhen transfer saga in international soccer made me think of how immigrant talent is handled when interests no longer align. Can the immigrant say “no” with dignity?

The Kendrick Lamar–Drake feud was an interesting play of tactical intelligence and lyrical oomph. The spat was important to me because I admire both rappers deeply. More than a decade ago, on my first fellowship in Ghana, I played Drake’s “Forever” in my hotel room every day for three months while I worked out. Drake’s bildungsroman-type lyrics resonated with me, a young writer, wet behind the ears, given a huge opportunity to lay the founding stones of his career. Understand nothing was done for me, Drake sang, and my palms pressed against the cold tiles of the floor as I did push-ups, and my temples tingled because this dude was singing my writing life, and every morning I felt like I was destined for something.

The Kendrick Lamar–Drake feud was an interesting play of tactical intelligence and lyrical oomph.

Kendrick has the passionate delivery of Tupac. He makes me pause and connect with the spine of the world. He reminds me of the intensity with which I write. One day in 2014, I found a CD in the basement of Dodd Hall at FSU. It was by an obscure group called Quadron. I heard a rapper on one of the songs. A husky voice. Sounded female. The rap was not just melodic, the lyrics pithy and meaningful; the whole delivery was pure art. I wanted to know who this female rapper was, so I googled the song, only to find out the featured rapper was Kendrick Lamar. That’s how good he is. His quality is enduring. That’s one thing I hope for in my work.

Q: What are you working on next?

A: A novel about a grieving young man who’s absent when his mother dies and sneaks around the village digging up the earth to look for her.

Iheoma Nwachukwu is a fiction writer and poet. He has won fellowships from the Mississippi Arts Commission, the Michener Center for Writers, and the Chinua Achebe Center. His work has been published in Ploughshares, Southern Review, Iowa Review, AGNI, Electric Literature, Crazyhorse, and other venues. Nwachukwu is assistant professor at Eastern University and lives in Pennsylvania.