The Cultural Revolution as Subnarrative

In Chan Koonchung’s The Fat Years, first published in Chinese in 2009 and translated into English in 2011, a novel depicting a dystopian contemporary China, people collectively forget important events in recent Chinese history or remember them in a far more positive light, even inaccurately. One of these events is the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). In Chan’s portrayal, contemporary China is a dark, cynical place, in which people might willingly choose historical amnesia so they can focus on making money and spending it. As one high-ranking government official says in the novel, ‘Everybody was living very well and very few people had any interest in recalling the Cultural Revolution and June 1989, so those memories just naturally fade away.’[1]

What Chan describes in The Fat Years is not that far from the reality of modern China. Roderick MacFarquhar, a scholar of Chinese politics at Harvard University and a leading expert on the Cultural Revolution, commented in a recent interview with the New York Times:

No one talks about the Cultural Revolution in China today. People have got far more important things to think about than what happened 50 years ago. They’ve got to find better jobs, earn more money and send their kids to better schools. I know there is a Cultural Revolution museum in Sichuan, and there is a place in Shanghai where you can see Cultural Revolution posters. People have not forgotten the Cultural Revolution completely, but I don’t think it’s on top of their minds.

Both in Chan’s account in The Fat Years and in MacFarquhar’s remark, the Cultural Revolution is rarely spoken of by people in China because their priorities lie elsewhere, as there is no need, or clear benefit, for them to actively recall the past. Instead, they focus on the present and look ahead toward what they expect to be a brighter, better future.

There is another theory, however, that might explain why there is a conscious and collective reticence about discussing the Cultural Revolution, an explanation that is both more tragic and more poignant. The British-Chinese journalist Xue Xinran, who herself experienced the years of turmoil, says, ‘I was one of the lucky ones, I survived without going mad. But still there is a national self-censorship going on. Even 50 years on people still won’t, or can’t, talk about what happened.’

For various reasons, including state and indoctrinated censorship, guilt and self-censorship, those who lived through the Cultural Revolution are understandably unwilling to recall—or at least openly discuss—the events that took place.

Why this willed reticence? Why this self-censorship? Perhaps it arises from a sense of collective guilt. In Roderick MacFarquhar’s words:

The essence of the Cultural Revolution is not just that Mao unleashed it and caused the chaos. The essence is that the Chinese, without direct orders, were so cruel to each other. They killed each other, fought each other and tortured each other.

For various reasons, including state and indoctrinated censorship, guilt and self-censorship, those who lived through the Cultural Revolution are understandably unwilling to recall—or at least openly discuss—the events that took place during the decade that even the Communist Party itself denounced in 1981 as ‘the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the party, the country, and the people since the founding of the People’s Republic.’ And those who were born after the period, a period that has seen incredible economic development and improvements in welfare, often have a limited understanding of recent historical events in China and little incentive to find out more.

I am of course painting with far too broad a brush here, and it is certainly not the case that everyone in China has succumbed to self-imposed amnesia or censorship, otherwise there would be no discussion or debate at all about this period. Still, the common perception, perhaps exaggerated, is that Chinese people tend to avoid recalling and talking about the unpleasant, traumatic past.

While this collective amnesia, self-censorship, and lack of interest might afflict some Chinese writers and artists, those who did not personally experience the Cultural Revolution have less to inhibit them when fictionalizing the period using research into others’ lives, scholarly articles, and documents from the era. During the Cultural Revolution, China was closed to foreign influence, but more information has been made available now. It is not hard to imagine why people might be interested in the Cultural Revolution, which can be termed a ‘historical curiosity.’

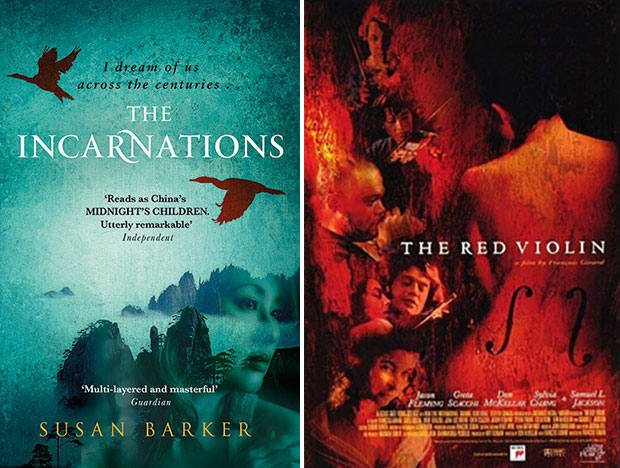

With this background in mind, I would like to look at two fictional texts, the novel The Incarnations and, to a lesser extent, the film The Red Violin, both of which span multiple historical periods and include a section addressing the Cultural Revolution. I will discuss the implications of this narrative choice. My aim is modest and I will not attempt to formulate an overarching theory about the representation of the Cultural Revolution in the West. Rather, I would like to use these two texts as case studies to see what kind of questions can be raised by their fictional appropriation of the Cultural Revolution.

The Incarnations is a 2014 novel by Susan Barker, the daughter of a British father and a Chinese-Malaysian mother. Its main narrative is set in contemporary Beijing, to be specific, in the months leading up to the 2008 Olympics. However, this is only one of the narrative strands within the book, and through a series of extended flashbacks, the novel traces the previous incarnations of the main characters in five defining moments in Chinese history: the Tang Dynasty, the Jin Dynasty, the Ming Dynasty, the Qing Dynasty and finally, the Cultural Revolution. There is a suffocating, claustrophobic feel to the novel, as the characters’ lives intertwine and reconnect life after life, there seeming to be no way for them to escape from their linked fates. Interestingly, The Red Violin, the 1998 Canadian film directed by François Girard, shares a similar narrative structure, although in this case the protagonist is the stringed instrument of the title that travels through time. First made in Italy in 1681, the violin is passed between different owners and patrons in five countries, although the film focuses on four historical moments in particular, of which the Cultural Revolution in Shanghai is one.

A multiperiod narrative structure is not the only characteristic the novel and the film have in common. Both, in their sections on the Cultural Revolution, employ music as one of the reasons why certain characters are targeted as enemies of the Communist Party and subject to public denunciation. In The Red Violin, the political officer Xiang Pei, who owns the red violin passed down to her from her mother, faces prosecution because of her interest in Western classical music, which is considered bourgeois and counterrevolutionary. In The Incarnations, the character Zhang Liya, herself a former member of the Red Guard, is denounced for possessing, among other items, a record of a love song from Hong Kong, ‘with not a worker, peasant or soldier on the sleeve but a glamorous woman.’ Such a record would, according to official thinking, be associated with capitalism and decadence:

I take a deep, steadying breath. This record is from Hong Kong, the prison island where the British devils have enslaved our Chinese brothers and sisters. A Marxist-Maoist analysis of this song would most certainly reveal its hidden anti-Communist agenda, that the song intends to lure us from the path of socialism by corrupting us with bourgeois longings for romantic love. Oblivious, you sway to the music, your eyes shut.

‘Zhang Liya . . .’ I say, in a quiet but urgent tone, ‘maybe we shouldn't be listening to this anti-communist Hong Kong music. . . .’

That The Incarnations and The Red Violin, two narratives in different mediums and separated by almost two decades, use music to identify anti-Communist elements in the narratives reveals at least two things: first, it is commonly known that during the Cultural Revolution, many forms of music, including traditional Chinese music, classical Western music, and pop music, were banned. Music has the ability to cross and transcend cultures more easily than other forms of artistic expression because of its emotional immediacy and, in many cases, lack of reliance on spoken language. Seeing the potential and danger of music in promoting and propagating potentially antirevolutionary ideas and sentiments, only a limited range of music was officially endorsed during the Cultural Revolution, while other forms were deemed unsuitable and their performances outlawed, resulting in a kind of ‘dark age’ of musical creation and production. By extension, even the ownership of certain music instruments and artifacts, such as the violin in The Red Violin and the record in The Incarnations, were considered offensive and punishable. Second, and more importantly, the writers of The Incarnations and The Red Violin have opted for the use of relatively unchallenging plots to account for the unfortunate fate of the characters, plots that are easily accepted as believable and even ‘authentic.’

In Susan Barker’s The Incarnations, another commonly known detail of the Cultural Revolution—the Red Guards’ attack on their teachers—is also integrated into the narrative. One of the main goals of the Cultural Revolution was to undermine established forms of authority in a flourish of ‘continual revolution.’ Attempts to challenge the teachings and philosophy of Mao Zedong were met with accusations of being anti-Party. Mao Zedong identified ‘teachers at colleges, high schools and elementary schools, newspaper owners, play actors, novel writers, painters, movie makers’ as ‘representatives of the bourgeoisie that had sneaked into the party, government, army and cultural sphere.’[2] In this environment, teachers were often the targets of public criticism, and cases in which students hounded teachers to death were not unheard of. In The Incarnations, we witness the following relatively milder scene of teachers at the fictional Anti-capitalist School for Revolutionary Girls being berated and humiliated by their rebel students:

The teachers are handed pots and pans, which they are forced to bang in percussion as they straggle around the field.

A third-year girl called Shaoli shrieks the headteacher’s crimes through a loudspeaker: ‘Headteacher Yang Attempted to Overthrow the Communist Government and Take Over the Military! Headteacher Yang Attempted to Assassinate Chairman Mao!’

Headteacher Yang is stony-faced and unrepentant. Shaoli calls over Teacher Wu and tells him to slap the headteacher. When he refuses, a second-year girl beats him with a broom. They call over Teacher Zhou and, scared of being beaten too, she slaps Headteacher Yang to loud cheers. ‘Harder! Harder!’ shout their former pupils. Shaoli orders Headteacher Yang and Teacher Zhou to knock heads, and they headbutt each other like rams. ‘Harder!’ Shaoli shouts through the loudspeaker, like a ringmaster in a circus of humiliation and cruelty.

This school episode in The Incarnations, and the use of music to single out those who have supposedly betrayed or deviated from the revolutionary path, conforms fairly closely to the events of the Cultural Revolution, as indicated in the documented memories of those who survived the period. It also should be said that it conforms closely to our common understanding of what occurred during the period. Indeed, the novel presents a flattened, and even to some extent caricatured, representation of the decade-long tragedy, which resulted in the deaths of nearly two million people. In both novel and film, the historical catastrophe of the Cultural Revolution is only one of several historical moments being addressed, one stop in a tour of past human suffering. Its significance is thus diluted and at times reduced to a convenient setting, in which certain well-recognized elements from the period are appropriated and recycled as exotic plot intrigues.

In both novel and film, the historical catastrophe of the Cultural Revolution is only one of several historical moments being addressed, one stop in a tour of past human suffering.

There is, then, I argue, the danger of trivializing the Cultural Revolution (and other historical events of a similar scale)[3] in fictional appropriations by reducing them to a kind of historical trope. With this in mind, what are the moral and ethical implications of such appropriations, especially when the retellings tend to focus on a few known key ‘facts’ and little else? While all fictional accounts of history are necessarily limited in scope—it would of course be impossible to capture all the elements of an entire historical event—fiction does not necessarily trivialize historical happenings when it broadens and elevates our understanding of the past. However, when it shrinks history to its broadest strokes, as is the case in the two narratives under investigation, I feel it does a disservice to the historical memory it is ostensibly trying to recapture. That is to say, we generally think that specificity and detail in historical narratives and focusing on the experiences of individuals is an effective way of communicating the emotional honesty of the event. However, on the other hand, this technique risks reducing the event to a series of clichés, or to the unrepresentative experiences of one person.

I cannot offer a solution as to what is a better way to narrate the Cultural Revolution or who has the right to do so, though I could perhaps suggest objective academic research, engaging first-person memoirs, or perhaps distilled and reflective poetry—although these too, it must be said, also have their limitations and issues.

All that said, I do find a couple of things rather interesting and potentially allegorical in Susan Barker’s The Incarnations. As mentioned before, the characters in the novel are trapped in a kind of limbo, as they are reunited life after life in a perpetual dystopian loop through the centuries, even though their relationship with one another might change. On one level, this provides a comment about Chinese history—of the plus-ça-change variety—that despite its variations over thousands of years, for many Chinese the experience of history has consistently been one of suffering and turmoil. It can also be read, however, as a metaphor of cultural and historical inheritance, and the inevitable influence of the past on the present, as the characters literally continue their previous connection, albeit in different forms, different dress, in the next life, and the next, and the next.

Lastly, toward the end of The Incarnations, it is revealed that one of the characters from the Cultural Revolution section of the book, Yi Moon, who is also the girl who reports her friend to the Red Guards for possessing the romantic Hong Kong record, is the grandmother of a child from the present-day Beijing section of the novel. Yi Moon, or the grandmother, thus embodies the bloodline connecting the opening and closing sections of the book, that is, the twenty-first century and the Cultural Revolution, collapsing them into one unbroken tale. This concretizes and makes visible the continuation of the Cultural Revolution into the current century and reminds us that this decade-long trauma took place not so long ago and that many of its survivors are still alive, even if it is not often discussed in public or has intentionally been rendered distant or opaque in mainstream discourse.

Hong Kong Baptist University

[3] Also see Claude Lanzmann’s criticisms of Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. Lanzmann argues that Spielberg overpersonalized the Holocaust and made it a film not about the killing of six million Jews but the saving of 1,300. Some think there shouldn’t be fictional representations of the Holocaust at all.