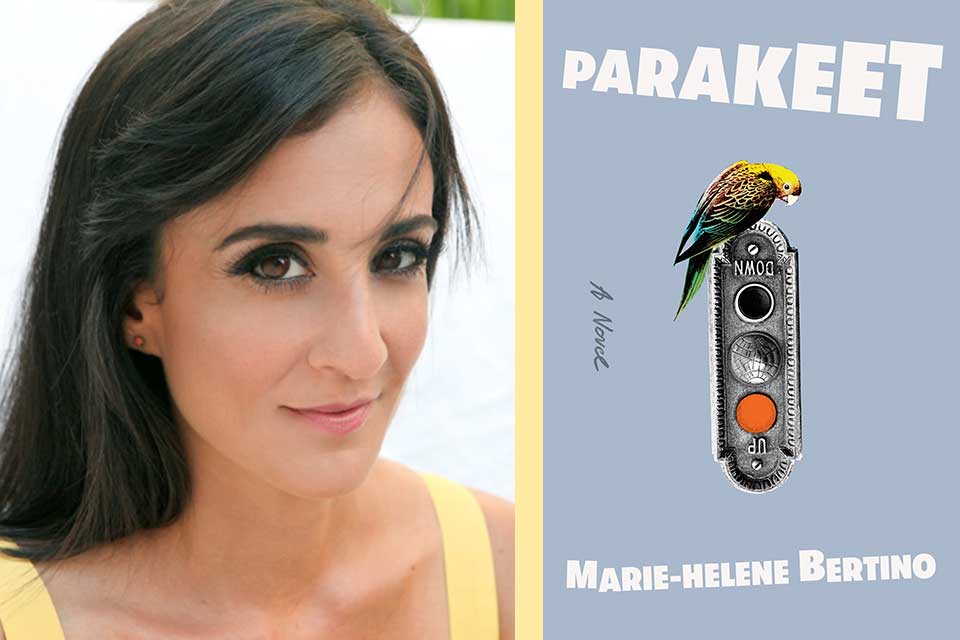

Parakeet Brings out the Delightfully Weird, Unexpectedly Wise Side of Marie-Helene Bertino

In this profile, one of Marie-Helene Bertino’s students at the New School provides a personal glimpse of the author, whose new novel, Parakeet, was published June 2.

On the evening of the National Book Awards, Marie-Helene Bertino strolled into our workshop ready for the after party adorned in a gold, sequined ball gown and black hoodie. There was already an electric air in the program that night, because we, her students—mostly aspiring and emerging writers—were impressed to know the faculty invited or involved in what we perceived as a night for authors who’ve Made It. Her hair had been curled—it was typically pin-straight—and accented with a rose behind her ear. She laughed and blushed at the compliments and laid her small, gold watch on the table next to her notes as she does in every class she teaches. She commands the space in a room: even with five minutes left before the start, our chitchat dies down, our attention drawn to her because she gives it back to us.

Even with five minutes left before the start, our chitchat dies down, our attention drawn to her because she gives it back to us.

On June 2, her second novel, Parakeet, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, hit the shelves. In the book, a soon-to-be-wed woman known only as “the bride” is confronted by her late grandmother, who takes the form of a bird. Her grandmother tells her to seek out her estranged brother, a reclusive writer who gained fame writing a play about the worst moments of his sister’s life. The bride finds her sibling, who shares that she has transitioned and goes by the name of Simone. Through whimsy and a mastery of craft, Bertino takes her protagonist on a raw journey toward her sister while her elaborate Long Island wedding plans collapse around her.

Bertino lives in Brooklyn and teaches creative writing at the graduate level at New York University, the New School, and the Institute of American Indian Arts. Her collection of short stories, Safe as Houses, won the Iowa Short Fiction Award in 2012. Her short fiction has appeared in Catapult, Tin House, and Guernica. Her writing, much like her personality, is surreal, funny, and unexpected, and through teaching, she inspires young writers to seize their voice and place in the world of writers.

Her writing, much like her personality, is surreal, funny, and unexpected.

According to Helene Bertino, Marie-Helene’s mother, her daughter has always been creative. During the summer before her eighth-grade year, in northeast Philadelphia where she grew up, Marie-Helene wrote her very first novel, “called The Dream Crystal, on an old word processor from Sears,” her mother said. Often Helene would bring stacks of white paper home from her job so her kids could play with it.

Bertino’s success was a long time coming. After being rejected from poetry programs, she found real skills in her Brooklyn College MFA in fiction but felt stifled by the way some of her professors defined the classics as old (or dead), white men. “I had nobody telling me what to read in a contemporary way,” she said. “But I’m also very bratty, and so I had a feeling that it was bullshit. I tend to be a loud mouth, and I have staunch opinions about art because it’s the thing I care the most about that’s not human.” She found a writers’ group and friends in her cohort and was introduced to the work of Haruki Murakami, Aimee Bender, and Yōko Ogawa, which made her feel like she had a home in crafting fiction because of their surreal, often very unusual writing.

For a while she worked as a biographer of people living with traumatic brain injuries for a plaintiff’s attorney, who taught her that lawyers tell stories in court to affect as much emotional resonance as possible. “It was less effective to write about pain straight on, like ‘my back hurts,’ and more effective to characterize the pain: ‘I can no longer lift up my four-year-old daughter.’” Her job was to write the narratives focusing on how the client’s life had changed on the emotional level, which taught her how to write about pain and its effects in her own prose: the bride in Parakeet has this same job.

Her job was to write the narratives focusing on how the client’s life had changed on the emotional level, which taught her how to write about pain and its effects in her own prose.

2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas, Bertino’s debut novel ( 2014), took ten years to write. “I worked my balls off,” she said. “Full-time jobs, waking up early to work on my novel, working at night, for years and years and years, getting nowhere.” Writing Parakeet was relatively pleasant, a refreshing change of pace, because she was “allowed by her editorial team to be as weird as [she] wanted.” Although the book is written from the perspective of the bride, her sister is integral to the story. I asked Bertino about writing across her experience as a cisgender woman: “One of my best friends lost her best friend, who was a trans woman, to suicide, and I was very much thinking about the unbelievable tenuousness of human experience, but particularly for at-risk communities.” Simone, a transgender woman, showed up in her writing and took over, becoming a much more central character than Bertino initially intended. “To me, the book is about two sisters. It felt important to represent Simone and her sibling relationship in a complicated way that reflects real-life experience.” She made sure never to speak from Simone’s point of view. “I did not feel comfortable doing that,” she said. Instead, Simone in a monologue to her sister tells only the facts of what’s happened to her.

Everything Bertino didn’t learn during her MFA she got working at One Story, a literary magazine in Brooklyn, where she started as a reader and finished as associate editor. She calls her time there her “Real World MFA” because she was exposed to the nuances of the publishing industry. Now, she feels her job is to grant access. “I can’t level the unlevel playing field that has existed for centuries before me, but what I can do is approach another’s experience with linguistic dignity.”

As a workshop leader, she is in control in the classroom but aware of where the heartbeats of her students lie. She’s a moderator who listens thoughtfully, includes everyone, and encourages earnestly. For a long time, though, she staunchly refused to teach. “I didn’t want to be a half-hearted teacher,” she said. “If I was going to do something half-heartedly, I wanted it to be something that didn’t affect human beings.” So, she was a receptionist. A jewelry customer service representative. Data entry. Until she taught the Gotham Writer’s Workshop in 2009 and loved it. Ted Dodson, a poet, editor, translator, and Bertino’s husband of five years, notices “she derives so much joy” from teaching but isn’t one of those “who tries to replicate their own mind in the minds of their students.”

Now that she’s teaching and writing full-time, Bertino is very specific about her schedule. “She’s very protective of her time,” says Dodson, “and she requires a lot of space and concentration.” She organizes her priorities and was steadfast when asked about it: “I have always known that I was a writer and so had this thesis statement of my life to refer back to whenever I had to make a decision.” When faced with a choice, she asks herself, “How does it affect the core of me, which is writing? How does it affect what I know is true?” She told me writing has been a divining rod for her. “It’s the reason that I know when I’m in the presence of bullshit,” she continued. “It’s the reason I know when I’m in the presence of bullshit artists. I just grew up knowing the real thing.”

New York City