Three Pre-Columbian Mythical Creatures to Enliven Your Waking Dreams

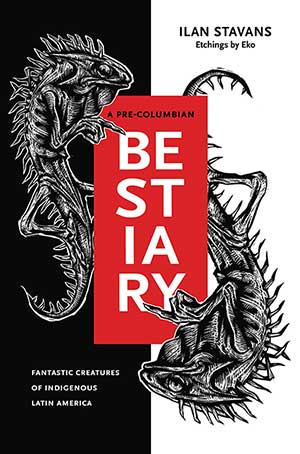

Next week, Penn State University Press will release A Pre-Columbian Bestiary, which the Press describes as “an encyclopedic collaboration between award-winning Mexican American scholar Ilan Stavans and illustrator Eko. . . . [The book] features lively and informative descriptions of forty-six religious, mythical, and imaginary creatures from the Nahua, Aztec, Maya, Tabasco, Inca, Aymara, and other cultures of Latin America.” The following is an excerpt.

Next week, Penn State University Press will release A Pre-Columbian Bestiary, which the Press describes as “an encyclopedic collaboration between award-winning Mexican American scholar Ilan Stavans and illustrator Eko. . . . [The book] features lively and informative descriptions of forty-six religious, mythical, and imaginary creatures from the Nahua, Aztec, Maya, Tabasco, Inca, Aymara, and other cultures of Latin America.” The following is an excerpt.

Azcatl

Azcatl

(ATZ-kah-tl, Nahua)

The Azcatl is an enormous ant, the size of three jaguars. Its body consists of a series of never-ending curves, which have the capacity to hypnotize its prey. According to the ancient Nahuatl legend, the original Azcatl was created in order to defend Aztlán, the “place of the herons.” It is the location—a kind of Xanadu, somewhere in today’s Utah or Nevada—from where the original Mexicans walked south in search of a place to settle. Their elders described their destination as a series of lakes with a rock emerging in the middle. A cactus would grow from the rock. On top of the cactus, an eagle would be devouring a serpent. Throughout their journey, the Azcatl protected the Mexicans by confounding their enemies through hypnosis.

In some graphic depictions, the Azcatl looks like a spider (Arachnida), with an internal respiratory surface in the form of tracheae, lateral and median eyes (ocelli), and sensory hairs that provide them with a sense of touch. In his diaries, Franz Kafka considered various words to describe the shape of Gregor Samsa, protagonist of the novella Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis, 1915), opting in the end for Ungeziefer, a term from Middle High German meaning “unclean animal not suitable for sacrifice.” In English, Ungeziefer has been translated as cockroach, beetle, and other insects. In passing, Kafka, who suffered from dream-like, hypnagogic hallucinations during a sleep-deprived state leading to the writing of the novella, mentions looking at a pictorial dictionary of Nahuatl creatures and pondering the Azcatl as an option. “Too seductive!” he states (entry of March 16, 1913).

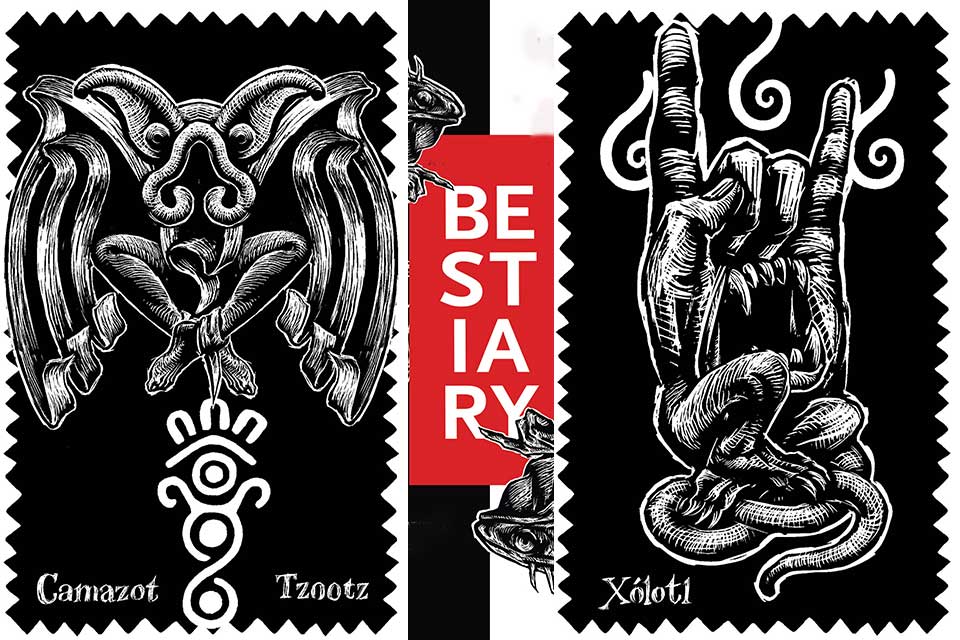

Camazot Tzootz

Camazot Tzootz

(ka-ma-ZOTH tzootz, Aztec and Maya)

Alternative spellings: Kamalotz and Cama-Zotz Sotz. Sotz are bats and Camazot Tzoots is a bat goddess. The literal meaning of her name in K’iche is “death bat.”

She is enormously flexible, growing or shrinking as necessary. Her aerodynamic wings are serpentine, twisting and turning in threatening fashion as she navigates the skies. She visits men who are disloyal, are unreliable, or have been dishonored in war. Her nose is a large hole around which a serpent-like edge simulates nostrils. Although she has human legs, knees, and feet, she seldom uses them. When overwhelming a victim, Camazot Tzoots emits a loud lethal sound. She drinks fresh blood. Yet she is gentle in her execution, avoiding as much as possible any suffering.

Camazot Tzootz makes an appearance in the ancient Maya book Popol Vuh, preserved through oral tradition until 1550, when the K’iche people made an effort to transcribe it. As they travel through Xibalba, the underworld, the twin protagonists Hunahpu and Ixb’alanke face the camazotz, bat-like monsters over whom Camazot Tzootz reigns. At one point, they spend a night in the House of Bats. When a desperate Hunahpu sticks his head out to find out if the sun has risen, the camazotz decapitate him. They take his head to the deities for their next game. They hang up the head as a ball.

According to Javier López Mezquites’s Luna sobre Mesoamérica (Moon over Mesoamerica, 1929), in the oral version of Popol Vuh, Camazot Tzootz asked for Hunahpu’s blood. Her request was denied after Ixb’alanke fought her.

Xólotl

Xólotl

(TCHO-lo-tl, Nahua)

The Xólotl is the Nahua god of light and darkness. He protected the sun from disappearing on the firmament. It is also associated with dogs, which, according to Hubert Howe Bancroft’s The Native Races (1883–86), are “in charge of leading the soul of the dead through the underworld.” But Xólotl is also about mutability. He has a stunning capacity to transform himself: he might be a dog with earrings at one point, an enormous mouth at another, a devouring tongue at yet another. The amphibian creature axólotl descends from him. The Argentine writer Julio Cortázar, whose novel Rayuela (Hopscotch, 1963) is about the inevitability of exile, paid tribute to it in an eponymous story. He portrays these salamanders as having Aztec faces. “I imagined them aware, slaves of their bodies, condemned infinitely to the silence of the abyss, to a hopeless meditation” (579).

Years ago, I had an axólotl. A shaman asked me to take care of it. Since it needed water, I placed it in a bathtub.

Amherst College

Editorial note: Excerpted from A Pre-Columbian Bestiary, © 2020 by Ilan Stavans, by permission of The Pennsylvania State University Press.