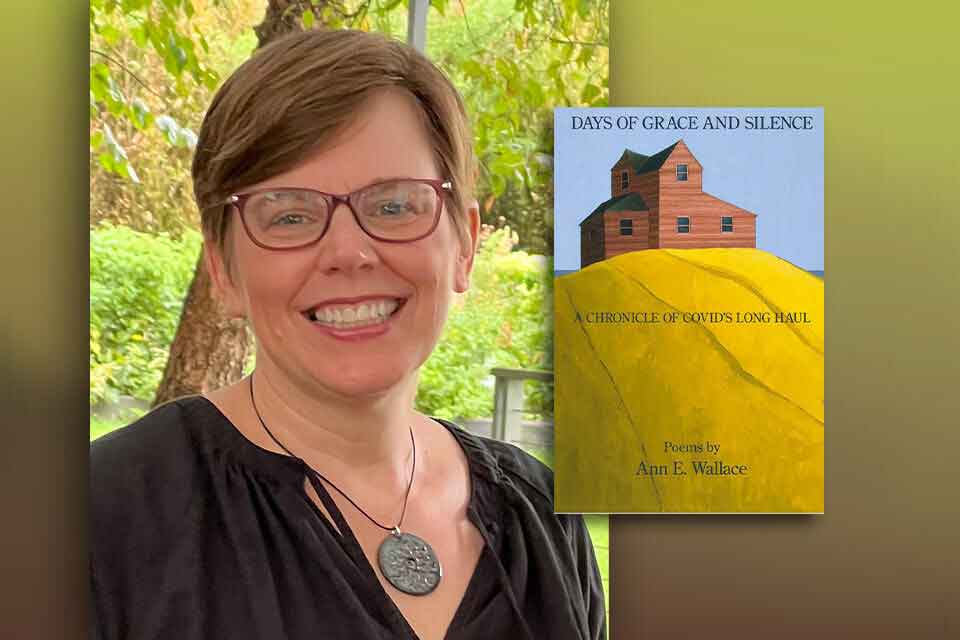

Writing Covid’s “Long Haul”: Ann E. Wallace’s Days of Grace and Silence

Covid-19 took the toll of over seven million lives globally since the pandemic began in late 2019. In the US alone the death toll estimate is more than a million. Yet this devastating tragedy has been quickly relegated to an unpleasant interlude of the past, replete with social isolation, vaccination, and masking that people are glad to leave behind as a nightmare from which they have satisfactorily transitioned to normalcy. However, this is an incomplete narrative that not only fails to memorialize those who died prematurely from the virus but also those who are still dealing with the continuing effects of long Covid.

Ann E. Wallace is a poet and scholar who has decided to use her latest collection of poems, Days of Grace and Silence: A Chronicle of Covid’s Long Haul (Kelsay Books, 2024) as personal testimony to record and bear witness to the pandemic when mainstream narratives have downplayed Covid’s devastation. Yet even though her collection is an intimate personal portrait of her struggles with the effects of long Covid, it is also a celebration of her community, its spirit of solidarity in supporting her slow and fledgling recovery.

Wallace’s poetic recording of her experiences with long Covid merge with flashbacks of her prior health challenges. Wallace is a long-term survivor of ovarian cancer as well as a patient of multiple sclerosis. The memories of these previous health traumas appear as flashbacks in poems like “Buoyed,” where she uses the image of a gale for a health crisis from which she made her “way / to a new shore.” “Training Ground” is another poem in which she chronicles the many diseases that she has survived.

The volume begins with a poem called “The Porches of Strangers,” which celebrates Wallace’s town, Jersey City, that has been performing ordinary acts of care and kindness during the Covid pandemic, offering meals to residents who are sick as well as “land-lost refugees.” While celebrating these moments of community, the poem ends with an image of a cardinal in a pear tree that Wallace planted in her yard. This return to nature as an act of spiritual and physical healing is a recurrent trope in the collection, seen in poems like “For the House of Finches” and “Tulips,” among others.

The return to nature as an act of spiritual and physical healing is a recurrent trope in the collection.

The collection is structured like a journal with dated entries beginning from March 2020 and ending with poems dated Spring 2023. As the reality of the virus engulfs the world, Wallace finds herself having to deal with her personal struggles during the pandemic. In poem after poem, she details the acuteness of her symptoms and their long duration. In poems like “Airborne” and “Breathless,” she details her inability to breathe, collapsing on the sofa. The personal health crisis is exacerbated by witnessing her daughter also go through the same disease. Yet, her daughter’s cough, “dry, relentless— / remind me / that we are /not yet destroyed.”

There is a steely determination to survive, evident in Wallace’s address to her students “To My Students in the Time of the Novel Corona Virus,” which she ends with the declaration: “and though you are struggling / you will not be broken.” However, this resolve seems to be brutally tested when in the next section of the book, an oxygen cylinder arrives at Wallace’s home, and she is tied to the tank by “fifty feet of green tubing.” The repetitive nature of the disease and her inability to rid her body of it finds the perfect expression in the villanelle “This Virus, a Villanelle.”

In the section “Sounds will Carry,” Wallace shifts her attention to her relationship with her partner and the loss of her partner’s mother. In the poem “Burning,” we are intimately in the presence of this woman now reduced to ashes in a box of cardboard. The mourning for this person continues in the poem “Lilac Season.” However, from this elegiac note the collection widens into mourning the loss of many unknown lives with a startling intimacy. In “Names I Do Not Remember,” Wallace describes dressing a dead woman in a white sari and painting her nails. In performing these tasks for the dead, Wallace is commemorating and humanizing the many lives lost to Covid-19, who have been denied these rituals of mourning and reduced to the anonymity of statistics.

Wallace is commemorating and humanizing the many lives lost to Covid-19, who have been denied these rituals of mourning and reduced to the anonymity of statistics.

In the final section, “The Infinity of Hope,” Wallace fuses present images of her encounter with long Covid with earlier losses. Yet the collection ends not with a sense of renewed suffering but with the possibility of hope and a belief in kindness from even random strangers to finally find comfort and healing in this world. The second-to-last poem, “Practice,” emphasizes the precarity of her beloved daughters getting very sick from Covid. In the last poem, “The Infinity of Hope,” Wallace leaves us with the image of expanding ripples of hope and kindness, perhaps posing a tenuous alternative to the devastation to which she has come so close to succumbing.

University of Wisconsin–Stout