The Search for Meaning in Ostap Slyvynsky’s Ukrainian Dictionary of War

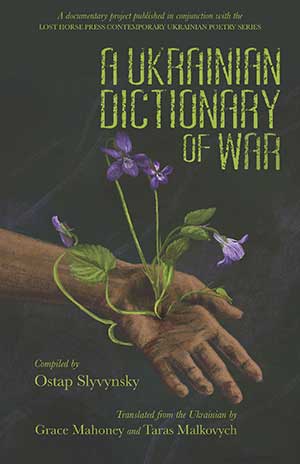

Like many other Ukrainian writers since 2022, Ostap Slyvynsky has answered a unique call of duty, one of cultural and lexicographical preservation. In his compilation A Ukrainian Dictionary of War (2024), Slyvynsky preserves the voices of those forced to leave their homes; of volunteers such as medics, soldiers, artists, and activists; of people interconnected by inexplicable grief, losses, pain, and turmoil. Translated from the Ukrainian by Grace Mahoney and Taras Malkovych and published by Lost Horse Press, A Ukrainian Dictionary of War—much like Oleksandr Mykhed’s The Language of War—dissects how even the simplest word’s meaning can change, transform, and contract during times of immense and intense emotion.

Like many other Ukrainian writers since 2022, Ostap Slyvynsky has answered a unique call of duty, one of cultural and lexicographical preservation. In his compilation A Ukrainian Dictionary of War (2024), Slyvynsky preserves the voices of those forced to leave their homes; of volunteers such as medics, soldiers, artists, and activists; of people interconnected by inexplicable grief, losses, pain, and turmoil. Translated from the Ukrainian by Grace Mahoney and Taras Malkovych and published by Lost Horse Press, A Ukrainian Dictionary of War—much like Oleksandr Mykhed’s The Language of War—dissects how even the simplest word’s meaning can change, transform, and contract during times of immense and intense emotion.

“My dreaming is more real than my waking,” says Stas from Kyiv in the entry titled “Bear.” Echoing other entries, Stas’s exhibits a nostalgic longing: “Today I wanted to go back to my childhood.” Stas shares that he “escaped” to “where there is no war”: “to Makiivka, Ust-Kamenohorsk, and Zakarpattia of my childhood.” “You must power through in order to think against reality,” states Stas—a testament to the myriad of ways Ukrainians have forged a mentality of determination and resilience, one that is informed by historical memories of generational oppression.

Stas’s narrative mirrors that of Olia’s in “Tickets.” “I keep thinking there is a parallel life somewhere. Where we are as we were before the war.” The tone of Olia’s thoughts is quite universal among Ukrainians, one that establishes a common thread in many of A Ukrainian Dictionary of War’s entries as well as a thread of recognition about Ukraine’s budding social, cultural, and economic promise.

In “Housing,” Dmytro (also from Kyiv) recalls seeing “smashed kitchens, remnants of bedrooms, nursery wallpaper, pieces of mirrors hanging in the bathrooms” as he looked at various buildings. Ironically, a sign in front of one of the buildings said, “At last! Some affordable housing for you!” Dmytro’s experience highlights a surreal reality for Ukrainians: amid the ruins of war, signs of a hopeful and promising future still remind them of the prosperous road Ukraine traveled prior to the war.

“Land” is a concise embodiment of the Ukrainian spirit during wartime. Halyna Dmytrivna from Bilopillia in the Sumy Region declares, “Of course, I planted the field. Absolutely!” She describes her house as “kind of gone,” but sowing her crops was a necessity. Her testimony is one that also reminds readers about the environmental toll Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has taken: “The land has also suffered. First it was littered with shell.” However, deminers came and “fixed” Dmytrivna’s land, leaving her to “take care of it” because “when you till a field, when you sow it, it’s as though you’re laying your hands on another person—stroking her skin, combing her hair.” Dmytrivna’s testament expresses how Ukrainians value nature and how the war’s devastating environmental harm is, essentially, personal for Ukrainians.

Other entries, such as “Letters,” by Nina from Konotop, attest to the artifacts from one’s life that become invaluable during wartime. Nina states that, as she packed for the bomb shelter, she grabbed “postcards of a special kind”—ones sent by her husband, a geologist who once traveled the Soviet Union. As she sat in the bomb shelter’s darkness, she took each postcard in her hand and “recalled the text.” “I hadn’t read them in ages, but they live somewhere in my memory.” The postcards act as a grounding force, one that centers Nina in the darkness.

Another piece, “Taboo,” examines the phrases that Ukrainians have quietly censored from everyday usage. Sashko from Kyiv shares “I used to say things like, ‘I had a blast’ when I really enjoyed something.” Sashko expresses that he “never thought twice” about using such phrases. However, now Sashko avoids using such language because such “words are taboo.” Sashko’s assertion reflects ideas about which writers such as Oleksandr Mykhed have written extensively. Like Mykhed, Sashko grapples with the fact that as reality shifts, so does language, and so does language’s purpose.

One of Slyvynsky’s own poems concludes the collection. The line “And after, we will also need to rebuild the language. / So that candle loses the adjective trench, / so the birds in our skies are only the kind with feathers.” In this poem, the compilation arrives full circle. For as much as the war has militarized the Ukrainian language, peace will hopefully demilitarize it, and—hopefully—the Ukrainian people will no longer have to have “lessons in sorrow.” Thus, A Ukrainian Dictionary of War is a haunting, necessary, and beautiful contribution to the Ukrainian literary canon. Once again, Lost Horse Press has displayed its knack for acquiring and publishing definitive Ukrainian/English dual-language editions—a form or cultural preservation entirely its own.

Southern New Hampshire University