Piercing the Veil: Laura Makabresku’s Mystical Testimony

While war, injustice, and spiritual fatigue continue to poison the air, Yahia Lababidi finds a beauty-infused resistance in the surreal work of Polish photographer Laura Makabresku.

I’ve long admired the surreal, sacral art of Polish photographer Laura Makabresku (born Kamila Kansy). But in recent times, amid escalating political noise and dispiriting violence, her serene images have taken on a deeper resonance. When words fail, as they often do, Makabresku’s painterly photographs feel like restorative pilgrimages to a finer realm.

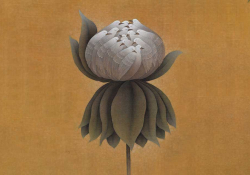

Makabresku identifies as a storyteller and creates haunting, sometimes hallucinatory scenes that feel like visual psalms or quiet reminders, amid the chaos of modern life, of what is indestructible. Her artwork inhabits liminal spaces—between seen and unseen, waking and dreaming, presence and absence—inviting us to dwell at thresholds. We are summoned into her enchanted world for a prayerful pause illuminated by candlelight, shrouded in gauze—to contemplate subjects that are less real-life portraits than apparitions: spirit-bodies caught between wound and wonder.

A student of magical realism and fairy tales, Makabresku draws deep inspiration from mysticism. Her figures, imbued with a devotional undercurrent, resemble modern-day icons calling us to surrender to the Unseen. It’s the spirituality of saints and martyrs, of longing and visions—Julian of Norwich meets Sylvia Plath. In her evocative visual lexicon, birds, doves, wings, and feathers recur frequently: symbols of the soul in flight, messengers of peace, and echoes of the Holy Spirit. As someone personally enamored of winged creatures and who tends to see our feathered friends as angels in disguise, I’m especially drawn to how this subtle artist centers avian creatures amid grounded suffering.

A student of magical realism and fairy tales, Makabresku draws deep inspiration from mysticism.

There is one Makabresku image I’ve returned to almost daily these past turbulent months, and each time, it puts my heart at ease. Vigil depicts a robed figure—monastic, androgynous—holding a slender lit candle close, as though guarding it against the encroaching dark. Small, colorful wild birds (most likely sparrows or finches) delicately perch on the figure’s forearm, gazing at the flame and nestling in the wide sleeves, as if drawn by some invisible liturgy.

I suspect there might be an echo of St. Francis here—patron of creatures and friend to the brokenhearted. Whether rendered in spectral black-and-white or bathed in the soft warmth of color, both versions of this image exude a steadying tenderness and the reassurance of ritual. It may be unclear whether we are witnessing mourning or prayer, but we sense that some quiet spiritual balancing act is taking place. To attend to this vigil with humble attention and reverence is, I believe, to partake in its calming benefits.

In times of upheaval, personal or collective, I often turn to art as a kind of silent scripture. Makabresku’s spectral compositions remind us not to be deceived by the darkness of our age and that the sacred still breathes persistently among us. As a visual poet, Makabresku uses her camera not to document our mutilated world but to consecrate it. Her ethereal art evokes a sacred interiority: timeless figures wrapped in linen, captured in states of ache or ecstasy; mythical and historical tableaux where breathing slows and the soul draws near to its Source.

As a contemplative artist, it’s evident Makabresku draws on that capital of riches, silence. And, in turn, her visual meditations silence us. By association, I am reminded of this wise counsel by beloved American poet Wendell Berry, found in his poem “How to Be a Poet (to remind myself)”:

Accept what comes from silence . . .

Of the little words that come

out of the silence, like prayers

prayed back to the one who prays,

make a poem that does not disturb

the silence from which it came.

Similarly, the human figures in Makabresku’s prayerful art are transformed into vessels of transcendence, rendering the ordinary into a state of the numinous. Through the holy hush of her visual meditations, she transports us to a place of infinite patience where we might reflect upon the radiance of our wounds and how the light enters them.

While war, injustice, and spiritual fatigue continue to poison the air, Makabresku’s work feels like a form of beauty-infused resistance. In our age of unholy brutality and destruction, her art elevates, a fragile testament to the eternal.

I reached out to Laura to ask about the spirit behind her images. Her answers, like her art, are tender, elliptical, and luminous. What follows is a brief exchange with an artist whose work offers a quiet but powerful kind of grace.

In our age of unholy brutality and destruction, Makabresku’s art elevates, a fragile testament to the eternal.

In Her Words: Laura Makabresku

Yahia Lababidi: Your photographs often feel like silent prayers or visual psalms. Do you experience your art-making as a spiritual act?

Laura Makabresku: Yes, I often experience image-making as an expression of my deepest spiritual longing—the desire that one day I may become as I appear in some of those images—that my soul may be united with God in love. These images are often saturated with longing, a silent and at the same time fervent cry to God, a constant search for His presence in everything, including my creative work. On one hand, they express a desire for unity, but on the other, they also bear witness to an actual experience of His closeness, a partial and still incomplete fulfillment of that desire, yet one that sustains hope.

Lababidi: In a time when the world feels increasingly brutal and chaotic, your images offer a quiet, sacred refuge. What role do you believe beauty plays in dark times?

Makabresku: I believe that beauty heals, lifts the spirit, offers comfort, soothes the pain of existence, and points toward meaning. I’m thinking not only of beauty expressed through art but also of beauty perceived in another person, in a meeting, in nature.

Lababidi: Your work is steeped in stillness, suffering, and symbolism. How do pain and transcendence meet in your visual language?

Makabresku: I think suffering is an inseparable part of our lives. That’s why I don’t try to avoid this “motif” in the stories I tell through images or words. We don’t always find meaning in painful or difficult experiences—even if we’re people of faith, there are moments when darkness, fear, and suffering seem to consume our thoughts and even our faith. Yet deep within, I sense that the flame of faith and hope inside us is sustained not by human strength but by God’s power. That’s why it burns even when our minds can’t perceive it and our feelings can’t sense it.

The very fact that I can try to express pain . . . to share it with another person—whether through simple words or metaphor, through image—is an experience that reaches into the depths of the soul and transcends the purely physical. Suffering is a mystery. I don’t try to unravel it. Instead, I try to weave it into a story greater than myself and my own experience—the story told in the Gospel. In its light, even the most painful experiences can take on meaning.

Lababidi: There are recurring motifs in your art—veils, wounds, candles, birds. What do these symbols mean for you or point toward?

Makabresku: Yes . . . throughout the time I’ve been creating, something like a personal visual vocabulary has developed—motifs and symbols that return again and again. For me, the closest ones are those connected with wounds, blood, the heart, birds, bare feet, and an empty vessel awaiting grace. Of course, these symbols can be interpreted on a cultural level—linked to archetypes, the Bible, myths, and fairy tales. But for me, they primarily carry spiritual meaning—they are vessels for spiritual truths and mysteries.

I use them mostly intuitively . . . and freely. I don’t aim to create images that function as riddles to be intellectually decoded. I believe that even people outside of the Christian tradition can grasp and experience the symbols in my work on a deeper level. It doesn’t have to happen through the intellect. I trust that the intention behind my images (which is a form of prayer) is a kind of energy that can offer something good to those who receive them.

Lababidi: Do you feel part of a lineage of mystic or visionary artists? Are there writers, painters, or saints who have shaped your inner world?

Makabresku: It depends on how you understand the word “mystic.” To me, mystics are people who dwell in God’s presence in daily life, who can see God’s action in everything, who love silence, and are open to love and self-giving. I feel that the word “mystic” in everyday language has come to describe people with extraordinary or spectacular gifts—visions, ecstasies, spiritual consolations. Or artists-prophets with inspired genius. Well . . . I don’t see myself that way. I’m a simple girl, with no formal art education. I don’t experience visions or ecstasies. I see and experience myself rather as a sinner to whom God, every day and every moment, shows immense love, tenderness, and mercy. And the comfort I receive from Him, I try to share with others—through art, yes, but also through ordinary gestures, words, and presence.

As for people who have shaped my inner world—there are many beautiful souls to whom I owe so much. . . . First of all, I think of the Carmelite saints, because that spirituality is closest to my heart and way of feeling: St. John of the Cross, St. Teresa of Ávila, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, St. Elizabeth of the Trinity. . . . I also owe much to the great teachers of prayer—especially the Desert Fathers—but also writers like Thomas Keating, Thomas Merton, Henri Nouwen, Meister Eckhart, Charles de Foucauld, Kahlil Gibran, John Chapman, Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, Catherine Doherty, and many more. . . . I should also mention artists like Rainer Maria Rilke, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Arvo Pärt.

Lababidi: Do you create with a specific viewer or feeling in mind, or is your work more like a private offering—to the divine, to yourself?

Makabresku: I think, in some way, all of those aspects are woven into my creative process—my relationship with God, my relationship with others, and my own self-reflection and healing. Sometimes one of those motivations becomes more dominant at a given time in my life, but usually they remain in harmony. I would be lying if I said I create solely for the glory of God. There’s still a lot of ego involved in the process, a lot of searching for myself. . . . But I try to reflect on that constantly, to move toward focusing less on myself and more on doing good, offering comfort, and simply sharing the beauty and divine presence that I myself experience in life.

Lababidi: Finally, what nourishes you—spiritually or artistically—in these times?

Makabresku: Above all, I think it’s personal prayer—by which I mean deep, silent prayer, rooted in intention and openness to God’s presence and action. Spiritual reading also sustains me and tunes my heart to remain attentive and aware in everyday matters. I also try to care for the hygiene of my mind—to avoid cluttering it with too many stimuli, information, images, and sounds. That doesn’t mean I avoid culture or contemporary art, but I try to engage with it in moderation. You can’t consume everything. It’s better to take in a little and savor its taste more deeply.

I believe our incapacity to feel reverence before the Mystery is at the heart of our time’s special barbarism.

Postlude: Art as Prayer in Troubled Times

American writer William S. Burroughs wrote of the “Ugly Spirit,” a pervasive, destructive, malevolent force that embodies cruelty, dehumanization, and chaos. This corrupting influence distorts reality, feeding on suffering and perpetuating cycles of violence, oppression, and decay, often manifesting in both societal systems and individual psyches.

Living as we do in the grip of this Ugly Spirit—the harshness and moral degradation that Burroughs describes in his disturbing work—we find ourselves under a shadow that threatens to eclipse the light. This spirit of distortion and cruelty seems to have taken root not just in our external realities but in our collective consciousness. It permeates the air we breathe, feeds the news cycles, and, at times, feels as though it were possessing us.

Yet, in the face of this consuming darkness, an indomitable beauty soars, rising above the sordid world to reassure us of what remains unassailable: incorruptible hope. Laura Makabresku’s work stands as a mystical testament to this aesthetic resistance. Her photographs, each an invocation, are not mere reactions to the world’s violence; they are odes to something unshakable and chaste—beauty’s steady persistence in the face of what seeks to annihilate it. Her art does not deny the wounds that we carry, nor the sad times we live in. It speaks beyond them, to a place untouched by this Ugly Spirit.

I believe our incapacity to feel reverence before the Mystery is at the heart of our time’s special barbarism. In a world increasingly defiled by the profane, art like Makabresku’s becomes a kind of spiritual protection, a talisman that shields our souls from despair. Such otherworldly art is a sanctuary we visit so that we can return to this world, spiritually refreshed.