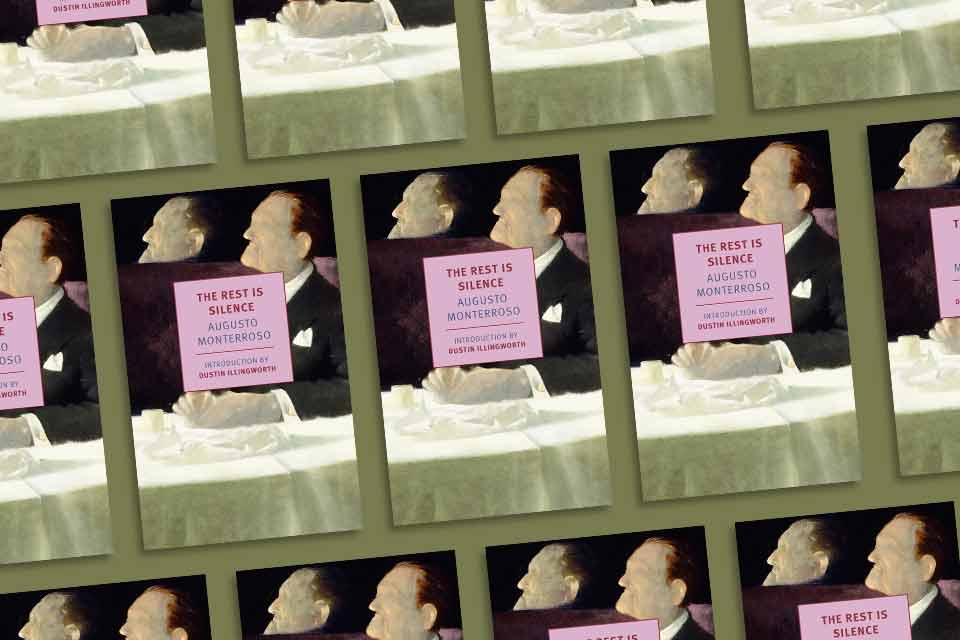

Precious Madness: Augusto Monterroso’s The Rest Is Silence

Augusto Monterroso (1921–2003) was an author immersed in the Western literary tradition. His first readings were of classical authors and the Spanish Golden Age. When he finally decided to write, he faced the challenge of being original in an era when everything seemed to have been written. He fought with the weapons of his great culture. In 1959 he published his first book, Obras completas (y otros cuentos) (Eng. Complete Works [and Other Stories]). He received the praise of, among others, Italo Calvino, who wrote in his Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, which he was to give at Harvard: “I would like to prepare a collection of stories consisting of a single sentence or even a single line. But so far I have not found any comparable to that of the Guatemalan writer Augusto Monterroso.”

Ten years later he published La oveja negra y demás fábulas (1969; Eng. The Black Sheep and Other Fables), a book of fables with no moral. Then came Movimiento perpetuo (1972; Eng. Perpetual Motion), which created a new literary genre: a genre that is neither poetry, essays, nor short stories but is at the same time all of them. That is to say, in 1978, when Monterroso published The Rest Is Silence (Lo demás es silencio), he was a mature author who had achieved the recognition of his peers. His work was of great thematic complexity and formal innovation. Monterroso was a bookish author but at the same time accessible and entertaining.

Aaron Kerner’s English translation of The Rest Is Silence (New York Review Books, 2025), introduced by Dustin Illingworth, preserves all the strength and variety of the original. The novel is a sort of imaginary biography of the (fictional) scholar and intellectual, Eduardo Torres. The narrator conducts a series of interviews with people who knew Torres and then collects his essays, articles, maxims, and even his illustrations. The tone is clearly parodic: Torres constantly makes mistakes in quotations and textual references. The clearest example of this is the title of the novel itself. Torres thinks that “The rest is silence” is a quotation from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, when we know that it is in fact from Hamlet.

There are seven literary genres in the novel: testimony, essay, maxim, academic analysis, epigraph, list, and addendum.

There are seven literary genres in the novel: testimony, essay, maxim, academic analysis, epigraph, list, and addendum. Each of these genres is exemplified by a unique and original voice. At the beginning, in the testimonial section, we hear a spectrum of voices ranging from the scholarly (a friend of Torres) to the digressive (Torres’s personal secretary) and the colloquial (Torres’s wife). Then we have the voice of Torres himself, who strives to be scholarly while revealing his ignorance. Monterroso’s humor is parodic, requiring a textual or artistic reference for it to be understood. There is, therefore, a very complex game with the reader, who must always remain alert in order to understand the joke. Kerner’s translation allows this game to be activated. It also has a section of notes that clarify some points about Latin American and global literary traditions. In the section of aphorisms and maxims, we see the Monterroso of the minifiction, a genre for which he is internationally recognized. The novel ends with a burlesque poem and its analysis.

In The Rest Is Silence, literature is verse and reverse, it is staged inside and outside the text, it is poetic and practical. Hence reading it is extremely pleasurable for those of us who enjoy complex metafictional literature. Latin American critics likened Monterroso to Jorge Luis Borges. Now that his work has been translated into English, another author with whom he could be compared is Vladimir Nabokov, author of The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Pnin, and Pale Fire.

Monterroso had a complex relationship with the United States. He was very fond of Anglo-Saxon literature and was thrilled when Edith Grossman translated his first book of short stories, which was published by the University of Texas Press. Grossman received an award for this translation and would go on to translate the work of Mario Vargas Llosa, Álvaro Mutis, Gabriel García Márquez, and, finally, Don Quixote. Years earlier, Monterroso was invited to attend a conference at the University of Michigan. He was stopped by immigration officers and interrogated about his political convictions. When he answered that, in order to know them, the agent would be advised to attend his lecture the following day, the agent refused him entry and sent him back on the next plane. Upon his return to Mexico, Monterroso wrote a letter, published in the newspaper Unomásuno, denouncing this incident: “These days in the United States there is so much talk about human rights, while in Guatemala 150 or more peasants (besides thousands of others in recent years) and as many Mexicans in the United States have been murdered by the Laugerud and Carter governments.” By this time, Monterroso had suffered a second exile because the government of Jacobo Árbenz, for whom he worked, was overthrown by an armed uprising financed by the CIA.

Monterroso suffered a second exile because the government of Jacobo Árbenz, for whom he worked, was overthrown by an armed uprising financed by the CIA.

Those were the years of the Cold War, and Monterroso was always a leftist intellectual. Politics barely seeps into his texts, but—as the scholar Gloria Zenteno wrote—it is noticeable in his literary forms and themes. He created new and original literary genres (such as minification, the open fable, and the genre in perpetual motion) that are now used by many writers around the world. In other words, from the periphery of Central America and then Mexico (where he lived for most of his adult life), this author wrote literature in creative and playful dialogue with the Western literary tradition. Aaron Kerner’s translation further consolidates Monterroso’s prestige and offers a chance for him to be read in the English-speaking world. The translation reflects Monterroso’s clear, concise, and transparent style as well as his variety of narrative registers.

Monterroso would have celebrated this publication. And we, his regular readers, who form a community of fans for his work around the world, are happy that New York Review Books has published his only novel.

In a personal letter that the academic Jean Franco wrote to Monterroso in 1968, she says with reference to the protagonist of this novel: “You have a voice so delicate and refined that almost no one hears you, but I assure you that in the midst of this vulgarity and carnival of authorities that is Mexican literature, each phrase of our friend Torres has the force of an atomic bomb. Think of Erasmus and cultivate your madness, which is a precious madness.”

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla