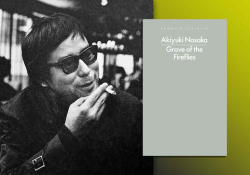

The Post-Partition Kaleidoscope of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s Stories

Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay (1894–1950) was an acclaimed Indian novelist and short-story writer who wrote in Bangla. His international fame mostly rests on the popularity of his novels Pather Panchali (1929) and Aparajito (1932), which Satyajit Ray adapted for cinema. It is unlikely that his other works have been seriously read across the world. Even within India, readers outside of West Bengal are unfamiliar with his creative abilities as a short-story writer.

Kaleidoscope of Life: Selected Short Stories (Hawakal, 2024), Hiranmoy Lahiri’s translations of sixteen of Bibhutibhushan’s short stories, will partially address this issue. Thirteen of these tales—the translator claims—have never been translated before. Lahiri’s selection includes a wide range of topics—from stories of “smugglers and dacoits, fictions of remote places and unusual personalities, and even supernatural narratives” (14)—thereby representing almost a cross-section of the author’s varied interests.

There are two significant aspects in Bibhutibhushan’s creative oeuvre. The first is his emphasis on representing ordinary people and their everyday life experiences. His short stories represent characters from all walks of life: village-dwellers, townspeople, men from different professional backgrounds (archaeologists, thieves, the working middle classes, and others). The second aspect concerns Bibhutibhushan’s focus on human relationships. Throughout his tales, which are based on many situations, the common thread is his broad humanistic engagement.

Throughout Bibhutibhushan’s tales, the common thread is his broad humanistic engagement.

Broadly, the contents of the present collection may be divided into three categories. Many stories deal with human experiences, relationships, and deep exploration of the human psyche. The second category deals with the supernatural, the spiritual, and the occult. The third category includes stories of adventure, themes of which are beyond the ordinary, a departure from the scenes of daily life. These stories focus not on the mundane and the everyday but on the exceptional. Some stories, however, tend to belong to more than one category.

The first story of the collection, “How I Began Writing” (Amar Lekha), is a fictive account of how the author commenced writing seriously as a career. Lahiri begins with this narrative probably because it is semi-autobiographical and thus sets an intimate tone for the volume. It draws on Bibhutibhushan’s own experiences as a village schoolteacher and his unusual friendship with Panchugopal, a young village poet. It narrates how Panchu literally forces the author to write a short story that is eventually accepted for publication in a popular city-magazine in Calcutta (this story is the second tale of the present volume, titled “The Disregarded”) and inaugurates his career as an author.

Human relationships and the workings of the human psyche constitute the focal point of seven tales in the collection. “The Disregarded” (Upekshita) examines the dynamics of a delicate brother-sister kinship that gradually develops between himself and a local married woman who reminds him of his long-dead sister. It brings him a sense of home in an unfamiliar place. Many decades later, he regrets his decision to leave the village for another job without informing the lady. “Discrimination” (Parthokyo) narrativizes the socioeconomic context of 1940s Bengal. The story explores the class-based hierarchical society of Bengal against the backdrop of the Bengal famine of 1943 and foregrounds how this experience was not homogeneous across all classes and backgrounds. “The Suitcase Swap” (Baksho Bodol) is much lighter in tone by comparison, exploring how the simple mistake of a luggage swap leads to two people falling in love and getting married (this tale was adapted for the cinema in 1970). “Theatre Tickets” (Theaterer Ticket) paints a very realistic picture of lower-middle-class life. It depicts the difficulty of life in shared accommodations, and how two free tickets to the theatre hold the promise of unbridled happiness for a working-class family that cannot afford to buy a few hours of entertainment. “The Manifestation” (Abirbhab) traces adjustment issues across generations in city-dwellers, who temporarily move to rural areas from Calcutta (now Kolkata) due to the shortage of resources after World War II. “Unbelievable” (Obishyashyo) paints the picture of two long-lost school friends reunited only to be suddenly parted by death.

Bibhutibhushan’s interest in the supernatural manifests itself in multiple ways. In “Archaeology” (Pratnotatto), he engages in fantasy writing. The story revolves around the archaeological findings of some pre-Gupta age artisanal objects and the narrator’s strange experience of meeting a sculptor in his dream—the spirit of a Buddhist monk who identifies himself as Dipankar Srigyan, a teacher of the Nalanda Mahavihar. “Gangadhar’s Peril” (Gangadharer Bipod) is an adventure tale, a thriller, and a supernatural tale all rolled into one. It is a kind of “cautionary tale” designed to “highlight the risks associated with the allure of quick riches” (19). “Jawaharlal and God” (Jawaharlal O God) reflects the author’s own disillusionment with the socioeconomic and political situation of India in the post-Partition, postwar era. God himself appears as a character in this satirical tale. “Motion Picture” (Chayachobi), set in Kashmir, despite dealing with the supernatural, easily qualifies as a travel story and an adventure narrative as well. “Taranath Tantrik” (Taranath Tantriker Golpo) is probably the outcome of the author’s personal quest for the metaphysical, brought about by the untimely death of his first wife.

“Jawaharlal and God” reflects the author’s own disillusionment with the socioeconomic and political situation of India in the post-Partition, postwar era.

“Chyalaram’s Adventure” (Chayalaram), as evident from the title itself, is a thrilling adventure story, set during World War II, about a village youth from Punjab who travels from Amritsar to Calcutta, France, Mesopotamia, and eventually Kabul, where he is caught up in a civil war. Bibhutibhushan’s description of countries and regions that he is personally unfamiliar with is extremely convincing. “Grandpa’s Tale” (Thakurdar Golpo) is simultaneously an adventure tale, narrating a young man’s experience of facing dacoits (a common menace back in the early decades of twentieth-century Bengal) as well as the story of meeting his wife. “The Web” (Jaal) narrates how a young man wandering in search of livelihood becomes a part of an old man’s vision of creating a settlement in a forest. “Not a Story” (Golpo Noi) is the narrative of a criminal (dacoit) who is transformed by an old Brahmin who chants the name of God.

The collection carries a long introduction and a useful glossary at the end. The introduction reflects the significant research done by Lahiri. It provides relevant background information on both the author and the selected stories, their contexts as well as publication history. Lahiri has gone through the author’s personal correspondence, biographical volumes, and original publication details (in Bengali) to provide detailed background information. This volume will prove to be a useful text in university courses on South Asian literature. It will provide the global reader unfamiliar with Bengali literature and its cultural milieu a realistic picture through these “‘slice of life’ stories” by foregrounding the cultural context of life in Bengal immediately before and after the independence of India in 1947.

University of North Bengal