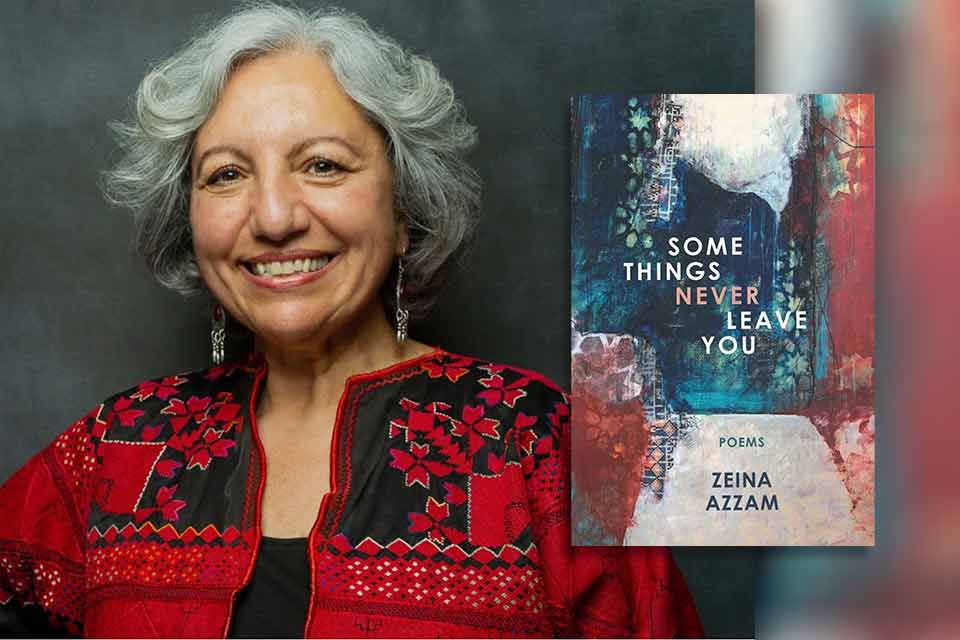

“Depth of Kinship”: Zeina Azzam’s Some Things Never Leave You

In Zeina Azzam’s mesmerizing collection of poems Some Things Never Leave You (Tiger Bark Press, 2023), tenderness means gazing directly at what both cuts and fills you. A universal factor of human existence is the need to enter an expressive space, which distills moments from one’s life into essences. Whether it’s standing at a parent’s deathbed wondering when the next reunion with a dying beloved will be or rejoicing at a child’s ability to enunciate Arabic letters despite truncation from the foundational homeland (Palestine), Azzam deftly parses the threshold of joys and losses and renders them in a breathless lyricism.

In one of the seminal poems in the collection, “You Could Tell Yourself,” Azzam invites the reader into a philosophical conversation with her soul as it struggles to make sense of death and transience:

You could tell yourself almost anything.

that when you look at your mother

on her deathbed you say well, she had a full life.

The poet is unsettled with the idea of her dying mother and refuses facile consolations. In this poem, she probes the meaning and magnitude of loss; ultimately for Azzam, these experiences are ineffable even as she runs her pulse across them. Later, she concludes with a certain wholeness or hard-won understanding:

You could then tell yourself that there are unnamable,

invisible hands that will continue to open, close,

flutter like leaves between you and your mother

and that maybe with the photographs

and the memories that come when you close your eyes,

that this is really all there is.

Azzam not only mourns the loss of loved ones in this collection but also celebrates the layers of her own hybridity.

Azzam not only mourns the loss of loved ones in this collection but also celebrates the layers of her own hybridity. In one of my favorite declarative poems in the collection, “I am an Arab American,” the poet describes what it’s like to have a dual identity, one that allows her a richness of allusions and a synthesis of perspectives:

Because I see Gaza when a protestor raises a fist in Ferguson

Because Abu al-Qassim al-Shabbi and Angela Davis inspire me to act …

Because I treasure coffee from Yemen, dates from Iraq, pistachios from

Syria, as well as pecans and corn and apples from Georgia, Iowa, New York,

Because I write in languages that flow in opposite directions

Because Arabic and English are my archetypes of sanctuary

In Azzam’s depiction, duality can be a “sanctuary,” a place and space that can produce confluences, a merging of seemingly oppositional forces, a fruition of sorts. By providing the reader with this flowing inventory of what it’s like to be “Arab” and “American,” Azzam challenges exclusionary manifestations of identity and amplifies the beauty and prowess of hybridity. The poet’s roving eye provides an affirmation for those who are perpetually bound by hyphenated identities, exile, and new belonging.

The poet’s roving eye provides an affirmation for those who are perpetually bound by hyphenated identities, exile, and new belonging.

One of the most stunning characteristics of this collection is the author’s ability to paint in language what she sees with her eye. Azzam’s intense observational powers are on display in her nature poems. Many of the poems in the book are odes to nature, including “Seen and Unseen,” “Peacefulness at the River,” and the “Physics and Chemistry of Things.” In “Imagine Jasmine,” the poet praises nature’s insistence on repetition and pattern:

Imagine singing the melody of the wood thrush,

a rooster’s sunrise refrain,

a bullfrog’s repeating bass-line,

a cicada’s see-saw ballad, I’m right here, I’m right here

In this intensely lyrical poem, the reader can be reassured by nature’s patterned language; Azzam’s lines are delicious gifts to be savored and remembered. She reminds the reader to seek (sometimes elusive) peace in nature, following in the steps of Wendell Berry and Mary Oliver.

Ultimately, the poet’s sojourn with nature allows her to be intrepid and to move forward in an unclear, often hostile environment where “this vaporous, hushed world / moves at sluggish pace.” If we follow Azzam to the river, we will also find rest where “left will be sky’s light blue / of peacefulness / and the bright clarity of water.”