The Childlike Daring of Ọlábísí Àjàlá, Global Citizen

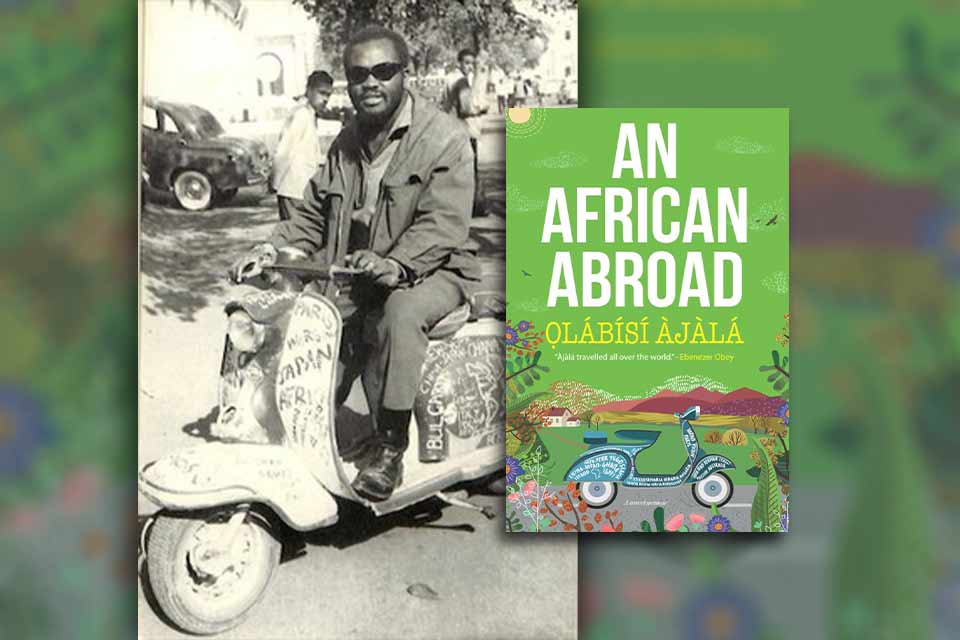

Nigerian journalist Mashood Ọlábísí Àjàlá (1934–1999), whose name became synonymous with the word “traveler” due to his reputation for wanderlust, devotedly detailed the experiences he accumulated on his audacious, fascinating journeys in his 1963 travelogue An African Abroad, which disappeared from the literary market as soon as its London publisher, Jarrold, ceased to operate a few years later. A new reprint edition, edited by Nigerian linguist and writer Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún and published by Olongo Africa, is set to ensure that Àjàlá’s status as a global citizen and his belief in the common humanity of all people endure in a postmodern world of transnational suspicion and transcultural intolerance.

Túbọ̀sún expresses this humanistic vision in his preface by sharing his hope that the reemergence of An African Abroad would “showcase for the historian of African and world history the evolution of politics, diplomacy, geographical boundaries, and journalism” and demonstrate “the wit and boundless optimism of the man bold enough to go where many of us today now merely aspire, limited mostly by the globalisation of paranoia.” The example of Àjàlá’s profound, unfettered humanity is especially relevant today in the wake of the post-apocalyptic evolution of the US presidential election campaigns steeped inexorably in dangerous racial trappings and ideological roadblocks; the shuddering, unbelievable nightmare that is the Israeli–Palestinian conflict; the covert but disturbing hostilities between Nigeria and South Africa; and the unconscionable desolation of the human past, present, and future that is the Russia–Ukraine war.

Àjàlá solely wrote An African Abroad longhand, but his wife, Joane, typed, edited, and transformed the manuscript into a delightful narrative in their Rose Bay home where they lived during the first two years of their marriage in Australia. In her foreword to the new edition, Joane recalls seeing a photo of Àjàlá on the front page of a Sydney newspaper in 1962, dressed in Yoruba attire and sitting on his famous scooter. A young Australian teacher who had a dream to teach in Nigeria, a distant country about which she was curious, Joane tracked down Àjàlá through the newspaper. When she eventually met the adventurer, Àjàlá’s interest in her swayed her into loving him. Following their separation after a nine-year marriage that produced three children, Joane returned to Australia, while Àjàlá settled in Lagos where he lived until his death in February 1999. He had meant for An African Abroad to be the first volume in his trilogy of travel books—an ambition the relentless achiever did not realize.

Àjàlá’s journey began in Ghana where he was born of Nigerian parents in April 1934. He grew up in Nigeria and attended Baptist Academy in Lagos and Ibadan Boys’ High School. In 1948, when he was eighteen years old, Àjàlá traveled to New York on a boat for further studies. He trained himself through three universities while working nightly at restaurants as a dishwasher and at hospitals as a morgue attendant. In 1957 he began his “one-man odyssey” around the world, traveling on his motor scooter. Àjàlá’s keen interest in people enabled him to obtain a deep knowledge of the culture, history, and politics of the countries he visited. His nuanced views about these places are exemplified in his depiction of the world of India as “one of mystery and dejection coupled with breathtaking culture and rich traditions.”

Àjàlá’s keen interest in people enabled him to obtain a deep knowledge of the culture, history, and politics of the countries he visited.

In India, Àjàlá and two Nigerian students he met in the country were harassed, arrested, and falsely charged by the police. When an inspector promised to free them if they agreed to keep the detention a secret from the Indian government, Àjàlá insisted on going to court, a decision characteristic of his tenacity for justice. On the day of the court hearing, the police altered Àjàlá’s charge and sent a man who was not at the scene of the arrest to testify against him. Realizing that the Indian was lying, the magistrate acquitted Àjàlá. Regardless of India’s seeming cultural diversity at the time of Àjàlá’s sojourn there in 1960, the adventurer was subjected to racist humiliations. In Calcutta, he was denied access to restaurants and social clubs, and when he insisted on being served, was threatened with forcible ejection and arrest. Unbroken by these acts of blatant racism, Àjàlá went on to bear witness to the unique preservation of Indian cultures, arts, and traditions, notwithstanding years of foreign rule and domination.

Àjàlá was neither a politician nor a diplomat, but his irresistible gift of presence endeared him to world leaders of his generation. At the time Àjàlá was in India with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1960, the country was being forced into a dispute with communist China over territorial differences, yet he managed to have a cheerful moment with Nehru, who sat on Àjàlá’s famous scooter at the end of their meeting. But Àjàlá’s travels were not always joyful. His first visit to Soviet Russia in 1957 brought him very close to the insularity of the European civilization of the time. Perhaps no incident demonstrates this European ignorance of a world beyond Europe as fully as the ludicrousness of the locals who asked Àjàlá during his second visit to Russia if black Africans were black because they drink black milk. His first visit to Russia was even more grueling because his movements were restricted, and he was closely monitored by Russian security forces. Upon his arrival in Russia, Àjàlá was forbidden from wandering about Moscow on his own and was warned not to interact with people in the streets. His cameras were seized and only returned on the day of his departure.

The Soviet obsession with foreigners affiliated with America and Britain was at its worst then, but the unorthodox manner by which Àjàlá obtained his visa to the Soviet Union may have complicated his situation. Yet his daring spirit shines through the many ways he subverted and transcended the obstacles he faced. Borders and limitations meant nothing to Àjàlá. To obtain the Soviet visa, for instance, he jostled through the Russian security while the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was delivering a speech in Berlin. He was arrested and detained by German officers and charged with being an American spy attempting an assassination on the Soviet leader. When Khrushchev learned about the detention, he ordered Àjàlá’s immediate release. However, before they freed him, the German police compelled Àjàlá to sign a false statement testifying that he was treated friendly throughout his custody. This culture of police brutality survives today and continues to undermine the democratic and civilized ideals of the modern world. From Hong Kong to South Sudan to Nigeria to Kenya and Bangladesh, civil movements against police brutality shimmer and burn brightly, even as protesters are systematically targeted and massacred.

Borders and limitations meant nothing to Àjàlá.

The valiant refusal of these protesters to be silenced—across countries and continents, cultures and races—is reminiscent of Àjàlá’s irrepressible commitment to the principle of human freedom. No matter what the stakes were, Àjàlá did not hide his opinions on global politics and political actors. On the Soviet leader, he writes, “I see Khrushchev, with all his virtues of leadership and oratory, as a braggart, an exhibitionist, a bully of the first order and an extrovert whose words one must evaluate thoroughly before taking them seriously at their face value.” In comparison to his predecessor Joseph Stalin, Khrushchev, Àjàlá remarks, “lacks the personal magnetism which was one of Stalin’s outstanding assets.” It did not matter to Àjàlá that Khrushchev freed him from detention. His allegiance was to the truth, his truth.

While in Iran, Àjàlá was determined to meet the Iranian head of state, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, not minding the weeks of tedious protocol and security measures required to meet the monarch, a private audience that proved difficult for even foreign leaders to obtain. Àjàlá had earlier profiled the Iranian leader as a dictator when he learned that the Shah had the political parties, government machineries, and industries in his country directly and exclusively under his control. But during their meeting, Àjàlá admired the monarch’s openness in responding to his questions. Regarding the monarch, he says, “Unlike most of the statesmen and leaders I have met, the Shah did not profess to know everything about Africa.” This is a commendable attribute given that much of the Western and European world had and still has vastly stereotypical views about Africa. Àjàlá concludes, “After I left him, I came to the happy conclusion that the Shah of Iran—King of Kings—like any other man is subject to joy and sorrow, success and failure.” This might appear simplistic, but Àjàlá was always probing for the complexities of life in both private and public relations.

The Middle East was no less politically and culturally complex than any other area Àjàlá traveled to. In one of his visits, he met a young Lebanese man, Ismet Taymani, who “bore violent hatred towards Israel.” There were many Arabs like Taymani who loathed the Zionists for displacing Palestinians. Some students with whom Àjàlá engaged held the opinion that “Israel is an illegitimate child … fathered by Britain, mothered by America and is now being nursed to maturity with the help of the UN.” But Àjàlá, ever humane in his assessment of things, advocated for a more tolerant world by asking the students whether they would harm an illegitimate child if they bore one.

Àjàlá traveled to Egypt with a plan to interview Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, visit the sphinx and pyramids, and Mount Moses in the Sinai Desert, a military zone at the time. To an Egyptian, these plans would seem impossible. But Àjàlá never quite seemed to grasp the concept of impossibility. As he toured the country, Àjàlá observed that the Arabs in Egypt were more tolerant of Jews than those he encountered in other parts of the Middle East. During his meeting with Nasser, Àjàlá asked the president whether he believed the Arabs and the Israeli could benefit from each other by coming to agreeable terms. To this enquiry, Nasser replied, “I don’t believe this will ever be possible. Neither of us would have anything to offer the other.” More than six decades have passed since Àjàlá’s sojourn in the Middle East, yet the relationship between Israelis and Arabs remains volatile.

Of all the countries he had visited at the time of writing An African Abroad in 1962, Àjàlá spent the most time in Australia. The section of the book dedicated to the country opens with this bold statement: “If there is one truly politically democratic country out of the eighty-seven I have seen so far, it is Australia.” But Àjàlá does not leave readers with a single impression of a place. He rides his scooter into Australia’s dark past and shameful present, revealing the cruel treatment of Australian aboriginals whose humanity the British colonial institution denied. He cites John William Bleakley’s The Aborigines of Australia to draw attention to efforts made by English settlers, who arrived in Australia in 1788, to exterminate the aborigines. “To a large extent,” Àjàlá notes, “the white settlers succeeded, particularly in Tasmania. In those days, Aborigines were hunted, tracked down and ruthlessly shot or beaten to death by white settlers.” Even when he reckons that the Australian government deserves praise for the country’s political and economic stability, “for the aborigines, the indigenous inhabitants,” Àjàlá concedes, “it’s a different story. For this minority group and race, Australia is a land of sorrow and misery.” Not so much has changed about the way Australia treats its aboriginal population today.

Àjàlá’s interest in history is piercing, refreshing, and intellectually motivated. An African Abroad not only offers a journalistic report of places but also serves as an informed personal account of the political and cultural history of the modern world. For its brutal honesty, subtextual complexity, and the childlike daring of its author, this travelogue deserves recognition in the canon of global travelogues beside such masterpieces as Marco Polo’s The Travels of Marco Polo as well as modern ones like Norman Douglas’s Siren Land.

University of Nebraska–Lincoln