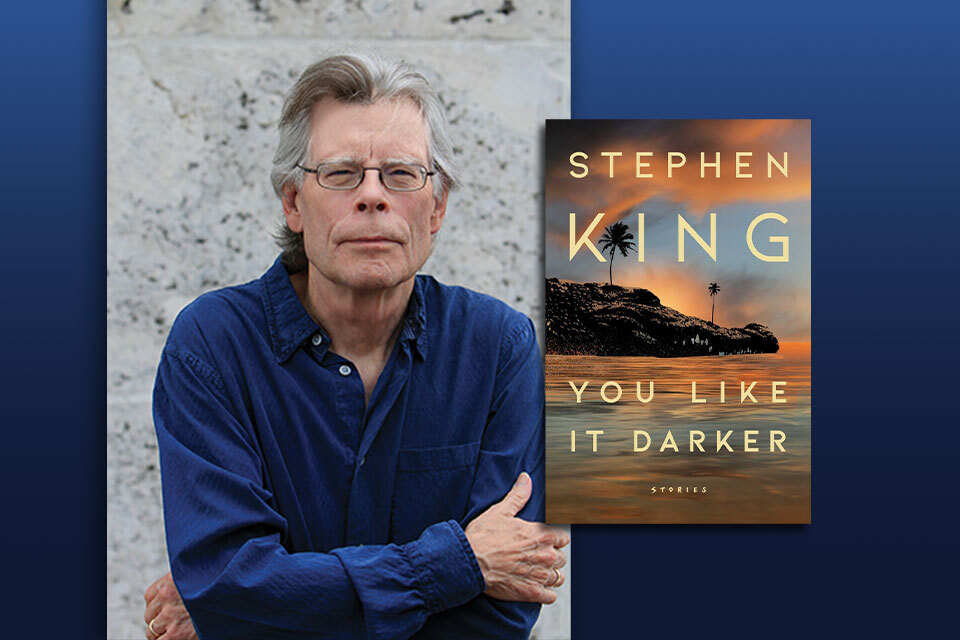

Brooding on Existential Mysteries in Stephen King’s You Like It Darker

As I wrote in World Literature Today some years ago, the quality of Stephen King’s writing abilities are all too frequently underestimated because of his popularity and several unfortunate movies made from his work (“Thoughts on a New Grandmaster,” May 2007, 16–19). Some reviewers grudgingly admit that he is a consummate storyteller or praise his grip on the public’s taste, but often even this praise is tempered with reservations about his being a “horror writer.” Judging a book by its genre is all too common, and not just by reviewers and readers—even publishers often present a book according to the category most likely to reinforce customers’ prejudices, not for what it is.

King is a legendarily prolific writer and, as he proves with You Like It Darker (Scribner, 2024), an extremely versatile one as well. At first glance, the book seems to be one of those desk-drawer-clearing books that eminent authors produce simply because they can. Short-story collections are not usually high on publishers’ commercial lists except when the author has picked up a Nobel or is practicing authorship in the beyond. Well, if You Like It Darker is one of these, it certainly indicates that there’s a lot of gold left in Mr. King’s bureau. Several of these stories are deeply emotional with rich but uncomplicated characterization, and overall the book incorporates the asking of what are usually said to be “the big questions.” Yet it does this without becoming pompous.

Take the story “Danny Coughlin’s Bad Dream,” for example. In it, a man has a dream that reveals the presence of a murdered woman buried behind a derelict gas station. Danny tries to do the right thing, to report it to the police, but doing so leads to his becoming the prime suspect. A major part of the book is devoted to this story, which has a number of twists and provides all the satisfactions of conventional mysteries. The story might have been published as a short novel similar to those issued in paperback in the noir era. Without revealing too much, Danny is trapped like the Hitchcock character in North by Northwest, complete with an Inspector Javert type detective who pursues him obsessively. It takes Danny, who is, except for his dream, a convincingly drawn ordinary guy, much effort to get himself out of this entanglement, but the most interesting element of his story is that the dream which provokes it all is never really understood or explained. We are spared the predictably unconvincing explanation.

With most writers of horror and suspense, one normally gets a good dose of explanation. There’s a witch or a talisman or the curse of something or other providing an explanation about why this innocent victim has been selected to struggle with the dark forces of evil. Few writers could pull off the kind of existential mystery that informs much of this book, but King makes it pretty much the theme of several of the stories. The mysterious and the inexplicable occur every day, it seems to say, but they are not necessarily good or bad. The explanations for them remain unknown.

Few writers could pull off the kind of existential mystery that informs much of this book, but King makes it pretty much the theme of several of the stories.

In another story, “The Answer Man,” one I find particularly moving, the life of a man is influenced, perhaps determined, by his amused encounters with the Answer Man, a roadside character who answers questions for a fee. The main character becomes a lawyer, fights in the Pacific in World War II, becomes a successful lawyer, and watches his wife decline into alcoholism. The Answer Man is never that specific or wide-ranging in his predictions, but like the Oracle at Delphi, is never wrong.

Are our destinies predetermined? Why does one man live and another die? How is it that one might do the right thing and yet be punished for it? King seems to be in an introspective mood, reflecting on the basic qualities of life itself, the questions even a casual observer of the human comedy might be provoked to ask. The title of the collection to me seems a bit misleading, as it implies more of the horror that King is known for. A number of the stories ask the serious questions without turning them into the dark. “The Turbulence Expert” gives us the premise that certain passengers on planes stabilize them, though they seem to be ordinary passengers. In fact, the first story in the collection, “Two Talented Bastids,” presents a couple of friends who, because of an encounter in the woods, abruptly develop certain talents that lay dormant in them. These talents are not dark curses, and the results are that they become remarkable in their fields. This unnamed thing happens to them and not even they understand it, any more than Shakespeare or Picasso or Einstein understood their own genius. It is as inscrutable a question as to why one kid becomes a great philanthropist and another becomes a serial killer. Questioning it provides few answers.

As might be expected, a few of the stories are weaker than the others, but they are shorter and still give up the kind of pleasure that an old episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents gives, with its trick ending. They are a kind of amuse-bouche for the more substantial, novella-length stories. We don’t read enough stories that operate on simple entertainment as the magazine racks disappear from the local pharmacy. Interesting, also, are the italicized notations at the end of certain stories. The most obvious one is a story called “On Slide Inn Road,” about a dysfunctional family taking a car trip. The story is followed with the phrase “Thinking of Flannery O’Connor,” and, of course, a reader familiar with “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” will immediately catch the resemblance, even though King’s story is different enough to stand on its own.

Another story is followed by “Thinking of John D. MacDonald” and is narrated in first person, unlike the other stories. Actually, it is another example of King’s ability to prove he is as much of a writing chameleon as a storyteller. His seemingly effortless style is what one would wish for in such a prolific writer and yet much more vivid than one might expect. This collection proves the fact that he is a master of conveying more than he gets credit for, with precision and insight.

Norman, Oklahoma

Editorial note: Launching tomorrow, the July 2024 issue of WLT is headlined by International Horror Fiction in Translation, guest-edited by Rachel Cordasco. The cover feature gathers stories by Junko Mase (Japan), C. E. Feiling (Argentina), Mahmoud Fikry (Egypt), and John Ajvide Lindqvist (Sweden), plus a reading list by Jess Nevins and online interview with Megan McDowell. Stay tuned!