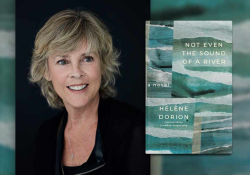

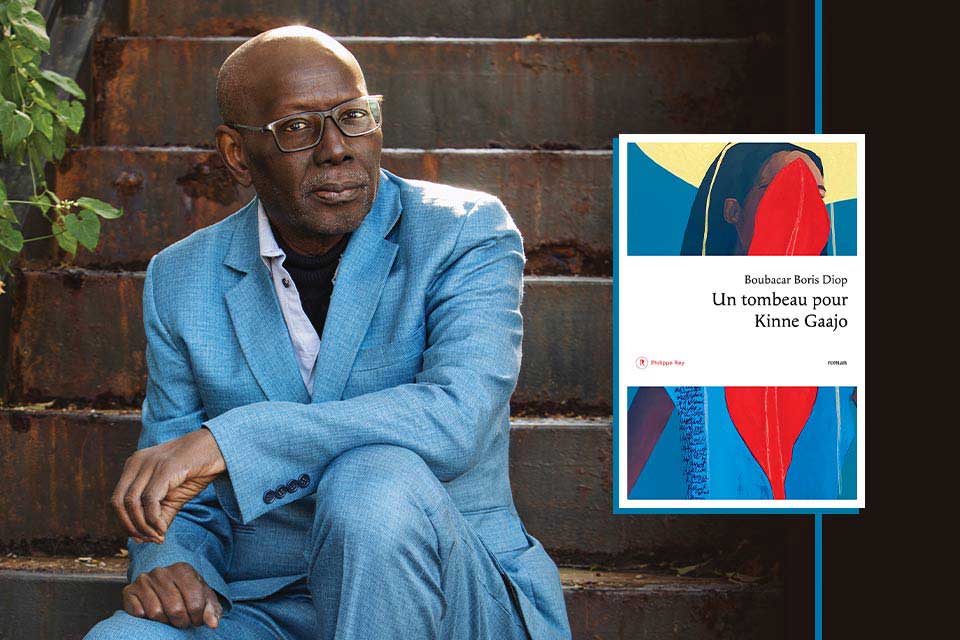

Boubacar Boris Diop’s Un tombeau pour Kinne Gaajo: The Value of Memory, Writing, and Translation

On September 26, 2002, Le Joola, the passenger ship relaying Dakar to Ziguinchor in the south of Senegal, capsized on its way to Dakar. The official death toll is 1,863, with 64 survivors, but many estimate that the number of dead was higher because the ship, which was designed to carry only 536 people, had close to 2,000 passengers, yet ticket counts are only 1,034. Survivors recount hundreds of people sleeping on the upper deck, making the ship tilt. Reports cite many reasons for the shipwreck, including weather conditions, mechanical issues due to poor maintenance of the twelve-year-old vessel, and ship operators who failed to follow maritime protocols. Still, overcrowding remains the primary reason for the disaster. The heavy death toll is exacerbated by the delay in rescue missions and the lack of proper rescue equipment. Over twenty years later, the shipwreck remains the second most disastrous nonmilitary maritime accident in recent history. Yet it is not known to the rest of the world, and even in Senegal, victims and survivors alike did not get worthy commemoration and reparations, and accountability actions remain tepid, with few officials being dismissed. Most of the blame was put on the captain, who perished during the shipwreck.

Famed Senegalese writer Boubacar Boris Diop is among the few to write about this disaster, first in his second novel written in Wolof, Bàmmeelu Kocc Barma [Kocc Barma’s Tomb] (EJO Éditions, 2017), now translated into French by the author himself as Un Tombeau pour Kinne Gaajo [A Tomb for Kinne Gaajo] (Philippe Rey, 2024). In Un Tombeau pour Kinne Gaajo, Diop alternates between journalistic commentary, historical accounts, and fiction, highlighting the importance of memorialization, accountability, the need for Africans to know their history, reflecting on language and the complexities of writing, and much more. Through the story of the fictional Kinne Gaajo, a woman who lived outside societal conventions and is one of the victims, the book commemorates the shipwreck while covering many issues concerning Senegal and Africa. Diop prompts us to ponder the role of fiction inspired by actual events. Kinne Gaajo may not have existed, but Le Joola did sink, and 1,863 perished that day. Every single victim deserves to be known and remembered. Of the 600 hundred women estimated to be on board, only one survived. There is one among those 599 who may or may not have lived like Kinne Gaajo. One wonders whether Boubacar Boris Diop uses Kinne Gaajo to commemorate the women on Le Joola, because there are many female characters in the novel.

Kinne Gaajo seems to be a fictional amalgamation of several Senegalese women writers who defy societal conventions in their personal lives and works, such as Ken Bugul, Ndeye Taxawaalu (Aminata Sophie Dieye, 1973–2016), Khady Sylla (1963–2013), as well as Khadidja, a character in Diop’s novel Un cavalier et son ombre (1997) [Eng. The Knight and His Shadow, 2015]. The main narrator, Njeeme Pay, is a prolific journalist who, like her best friend and soul sister Kinne Gaajo, flouts social rules through a loving marriage with a man of a different faith. Devoid of her friend’s remains, Njeeme attempts to bring Kinne back from the bottom of the ocean and bear witness to her free mind, memorializing her. Like Diop, Kinne Gaajo was passionate about the Wolof language and culture. However, like many artists, she lived at the margins of society, was lost in the universe of books, and engaged in sex work even though it is not clear whether to rebel against society or out of necessity.

As usual, Diop engages in criticism of the government and its failed politics, especially when it comes to the youth.

As usual, Diop engages in criticism of the government and its failed politics, especially when it comes to the youth. Tackling migration issues as the youth flee their unhomely Senegal to risk their lives in other boats that echo the Joola. If they did not die while crossing from Casamance to Dakar, they would die on their way to Europe onboard other overcrowded vessels.

Diop is no novice when it comes to writing about tragedy. His 1997 novel, Murambi, le livre des ossements, translated by Fiona Mc Laughlin as Murambi: The Book of Bones (Indiana University Press, 2016), is a seminal fictional account of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide and earned him the 2022 Neustadt Prize (see WLT, January 2023). Unlike in Murambi, where everything is sober and in alignment with the scale of the tragedy, Un Tombeau pour Kinne Gaajo has some lightness to it even as it points fingers at the Senegalese collective consciousness, guilting them for callousness with this tragedy. Yet the specter of Le Joola haunts in the national consciousness. As Professor Móodi Ba responds to Njéemé Pay, “Vous avez un peuple peut-être frappé par le malheur et l’oublier au bout d’un certain temps. Mais jamais il n’oubliera qu’il avait oublié ce Malheur” [You have a people who have been struck by misfortune and forgot it after a while. But it will never forget that it had forgotten that Misfortune] (49).

Diop highlights the importance of writing in local languages, makes a plaidoyer for Wolof, and celebrates Aram Faal, the Senegalese linguist who contributed significantly to promoting indigenous languages. He also reflects on literary craft and toys with readers, sometimes even stating that we should not take fiction seriously because the writer often only “raconte des histoires” [tells stories]. “Elle m’a dit un jour que l’art d’écrire n’a rien à voir avec des phrases fleuries ou des mots piqués dans le dictionnaire. Ils peuvent briller ou être agréables à entendre mais ne resteront pas moins du toc et tôt ou tard, ça se saura” [She once told me that the art of writing has nothing to do with flowery phrases or words swiped from the dictionary. They may shine or be pleasant to hear, but they’ll always be fake, and sooner or later, people will find out] (96). Diop ponders the solitude of writing: “Créer c’est tendre un miroir, faire écho à sa voix intérieure. Mais ce que je montre, transmet, je suis la seule au monde à le voir et à l’entendre” [To create is to hold up a mirror, to echo one’s inner voice. But I’m the only one in the world to see and hear what I am showing or transmitting] (96). The writer is then eternally misunderstood, not only because she is not making sense but also because one must access her deepest thoughts to understand what she is writing. Writers make many sacrifices to create a text for us while we live our lives, yet we expect them to prove something to us.

Diop also reflects on literary craft and toys with readers, sometimes even stating that we should not take fiction seriously.

Diop becomes a historian and brings to life figures like Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784), the first enslaved person to publish a book of poems in 1773, whose origins are traced back to the Senegambia region, and Sidya Léon Diop or Sidya Ndate Yàlla (1848–1878), the son of Ndate Yalla (1810-1860), the famed Queen of Waalo. Sidya was forcibly adopted by French governor Louis Faidherbe, who attempted to turn him into a French man by rebaptizing him catholic and adding Léon to the young man’s name, thus appropriating him and his identity. Sidya later renounced his alienation and became an anti-French revolutionary. Diop tells Wheatley’s and Sidya’s stories at length, at times chastising the Senegalese for not knowing these two historical figures.

Like his first novel written in Wolof, Doomi Golo (Éditions Papyrus, 2003), later translated by Diop as Les petits de la guenon (Éditions Philippe Rey, 2009), Diop offers a translation that is not faithful to the original and creates tensions between the roles of a writer and that of the translator. Translation is creation, a process during which the translator attempts to inhabit the universe of the author at the time of creation, something that is quasi-impossible, for as Diop says, story and novel events exist only in the minds of authors, and even what’s on the page does not render them correctly and completely. There is always a gap between a signifier and what is signified. What happens when the author himself is the translator is perhaps the continuation of the writing process or an opportunity to redirect, add, and re-present the story again. The Wolof version has more personality and linguistic insight. For example, in the first erotic scene between Bart and Njeeme to bid farewell to Kinne, the narrator addresses the reader directly, admonishing them to stay out of what she does at night with her husband. This address is taken out in the French version, making the eroticism mechanical.

Diop offers a translation that is not faithful to the original and creates tensions between the roles of a writer and that of the translator.

The title change, moving from Kocc Barma to Kinne Gaajo, conveys the shift in focus between the two versions. When the Wolof version focuses on the beauty and challenges of writing in Wolof, a language nicknamed “the language of Kocc Barma,” the symbolic figure who mythically enriched the language with most of its esoteric sayings and philosophical repositories, the French translation attempts to frame a story arc that at times feels forced. Un Tombeau pour Kinne Gaajo is a disappointment compared to the Wolof version, where the author’s ease and playfulness are seductive. Diop’s mastery of French is not in doubt, but his native language, Wolof, seems to be indeed the language in which he can marvel without telling a real story and get away with it. The Wolof version did not need a story arc or conflict to satisfy its readers. The language is a bold character in the novel, tongue-twisting and conveying thoughts in a Wolof that would make Kocc Barma proud. Kinne Gaajo is quoted to have said: “Une œuvre littéraire n’a de saveur que si elle vient de la langue de qui l’écrit” [A literary work is tasty only when it comes from the tongue (language) of the one who is writing it] (123). In the French version, the narrator acknowledges her rambling: “je n’en aurais connaissance que bien plus tard en consultant ses archives pour les besoins de cette biographie qui au fil des pages part dans tous les sens, je le concède humblement à mes lecteurs irrités” [I wouldn’t know about it until much later, when I consulted her archives for this biography, which, I humbly admit to my irritated readers, goes off in all directions] (126). Why the story of Jennifer Davies, the white woman savior? The story comes out of nowhere and only tells a little about the narrator or Kinne Gaajo. Even the near-mythical Céndu Siise, whom Diop tries to craft as enigmatic and exciting, does not add much to the character development or attempted story arc.

All these “shortcomings” in the French translation are the prerogatives of a writer with nothing to prove. Boubacar Boris Diop is one of the most prolific writers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, producing significant works across genres. He has a license to write whatever he wants and according to his rules.

Greenville, North Carolina