Translating Alice Walker: A Conversation with Manuel García Verdecia

In conjunction with Erik Gleibermann’s interview with Alice Walker that headlines the November issue of World Literature Today, I wanted to explore the bilingual presentation of Walker’s latest poetry collection, Taking the Arrow Out of the Heart (37 INK/Atria Books, 2018), as translated by Cuban poet Manuel García Verdecia. Via email, we struck up the following exchange.

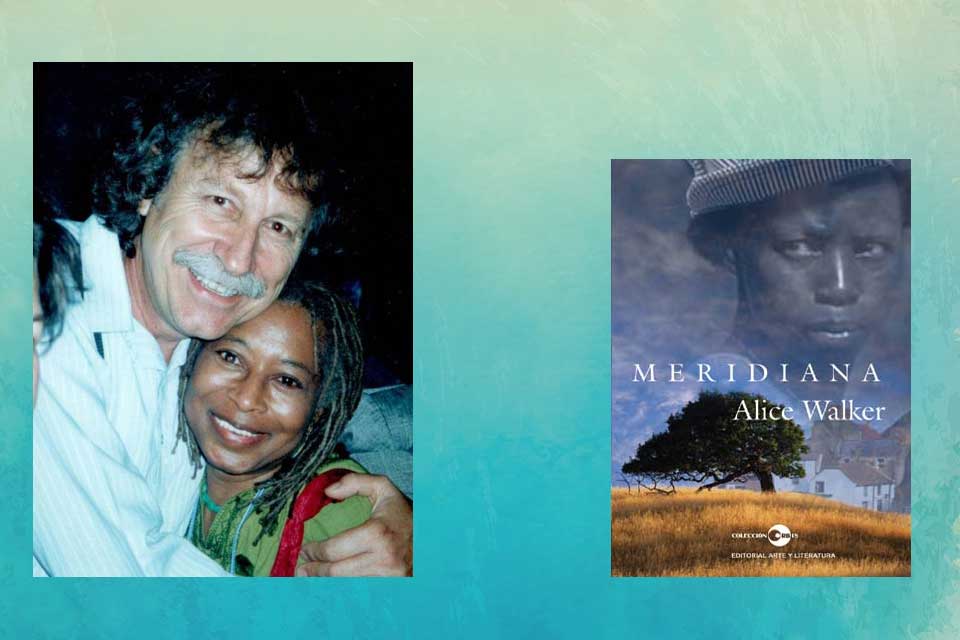

Daniel Simon: In the “Note about the Translator” that prefaces her new collection, Alice Walker recalls meeting you at the Havana Book Fair in 1985, where she gave a reading in a small auditorium that used to be Che Guevara’s office. Afterward, she describes a meeting of “true soul mates” (verdaderas almas gemelas) at a lunch gathering that included you and was marked by a “luminosity” in the moment that went “straight to [her] heart.” What do you recall most vividly about that luminous encounter?

García Verdecia: I will always remember her humble attitude as well as her vivid interest about everything that concerned us all. She is a person who radiates spirituality and enlightenment. Living in a world that has turned excessively materialistic and violent to share time and experiences with such a soul helps strengthen the feelings and ideas that one would like to prevail.

Simon: You’ve translated several of Walker’s other books, including the novels Meridian (1976), The Temple of My Familiar (1989), and Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart (2004). How has her work been received in Cuba?

García Verdecia: As you can imagine, Alice is a very well-known author in our country, basically due to her novel The Color Purple and its movie version. So this is a first element of attraction. The other things have to do with features of life that she re-creates and that also form a part of our social development, like slavery, ill treatment of women, poverty, mistreatment of nature, loss of faith, and the struggle to make life become meaningful. Our world is living a life of nightmares and ghostly images. It needs someone to show them life as it really is and worth living. That’s what Alice’s work does.

Simon: What challenges did you encounter translating her poetry?

Manuel García Verdecia: Translating is always a great challenge because one has to put oneself in the situation of the author, to try to feel and think like her. It means not only giving the substance of what she writes but, in some way (since art is basically a meaningful structured work), to let the reader feel the way she writes. What makes things more difficult is the use of certain idiomatic expressions or neologisms that reflect certain objects or phenomena that we do not have in our own reality. That’s when I use footnotes. But in general it is a very challenging and stimulating work that also helps me in my own development as a writer.

Simon: From the title of her latest collection (in Spanish, Sacándose la flecha del corazón) to many of the poems included, there is an elemental quality to Walker’s verse: darkness, beauty, grief, journeys, survival, witness, planting, eating, freedom, and prayer, among other themes, gesture toward rootedness in the quotidian as well as transcendence. You write about translating her work as “a work of intellectual and spiritual growth.” Do you have a favorite poem that exemplifies the spiritual growth you encountered in her work?

García Verdecia: Well, Alice’s work is characterized by her consistency and coherence in feelings and ideas. So one can find lines that make us think things over and look at life differently, here and there and everywhere. Our greatest poet, José Martí, wrote: “Poetry lives on honesty.” And this is the great thing with Alice’s poems. Her spirituality is deeply rooted in her being, and as she writes honestly it springs up at every moment. Anyway, poems like “The Long Road Home,” “The New Dark Ages,” and “Wherever You Are Grieving” help us find this spiritual force I speak about, and we thank her for them.

Our greatest poet, José Martí, wrote: “Poetry lives on honesty.” And this is the great thing with Alice’s poems. Her spirituality is deeply rooted in her being, and as she writes honestly it springs up at every moment.

Simon: In addition to that elemental and spiritual quality, many of the poems in Taking the Arrow also snap the reader back to specific people and historical moments: poets and revolutionaries like Muhammad Ali, Celia Sánchez, Samih al-Qasim, and Nelson Mandela, to name a few examples. She also writes fiercely about current and historical political and human rights issues, like child detention centers, occupied Palestine, and #MeToo. At the end of her poem “I Am Telling You, Discouraged One, We Will Win,” she writes: “If you don’t believe me / take the time to awaken / and truly witness / yourself.” Does such poetry of witness still resonate in Cuba?

García Verdecia: Of course, all these poems will resonate very deeply in our society. We are a people who have lived under a long Revolution (with its accomplishments and errors) and have suffered for many years the troubles brought about by our own leaders’ mistakes and by such illogical policies as the US embargo that brings a lot of trouble to our people. Like the Palestinians, many Cubans have fled the country looking for better conditions in the United States and elsewhere. We’re also poor people, and we know how Palestinians or other occupied peoples feel. Also, the lives of such leaders like Muhammad Ali, Celia Sánchez, Samih al-Qasim, and Nelson Mandela give us, not only a certain path to follow, but the necessary energy to maintain the struggle for a better world. Every day when one reads the news, if one is a decent and concerned person, one realizes that the spirit of such leaders is more necessary that ever before.

Simon: Is there a backstory from 1985 about her poem for Celia Sánchez?

García Verdecia: No, there isn’t a specific one, apart from her admiration for those women that break the rules of their time and fight hand in hand with men to make things change for the better.

Simon: At the end of “To the Po’lice,” Walker imagines the mothers of young black men killed by police shootings inviting the officers who killed their sons into a circle of healing. “Within that enclosure / Naked to their grief,” she writes, “Is where you must center / If you are ever / To be freed.” In some sense, “pulling the arrow out of the heart” might heal not only the wounded themselves but also those who inflict those wounds in the first place. And despite so much shattering violence in these poems (“the beast in so-called / civilized man”), Walker ultimately insists on “cobbling together the broken pieces / —left over from the beauty that is destroyed,” “raising the bar of love,” “hope rising,” and seeing “all loss . . . as a door.” What do you find most hopeful in these poems?

García Verdecia: The possibility that the persons who commit these crimes start feeling that we’re all human, independent from the color of our skin, the creeds we have in our heads, or the money we carry in our pockets. One must learn that he who shoots a young man is shooting a part of life, a part of him/herself, because we all belong to the human race. She makes us face the invisible part of our soul, as if going around the moon, and discover that we’re all children of God.

October 2018

Manuel García Verdecia (b. 1953, Holguín) is a Cuban poet, professor, editor, essayist, and translator. In addition to several novels by Alice Walker, he has also translated the work of Sylvia Plath, Walt Whitman, and Khalil Gibran. His many awards include the Premio Nacional de Poesía Adelaida del Mármol (2000), the Premio Nacional de Edición (2002), the Premio Nacional de Novela José Soler Puig (2007), the Premio Nacional de Poesía Julián del Casal (2007), the Premio Nacional de Poesía La Gaceta de Cuba (2008), and the Premio Internacional de Poesía “El mundo lleva alas.”