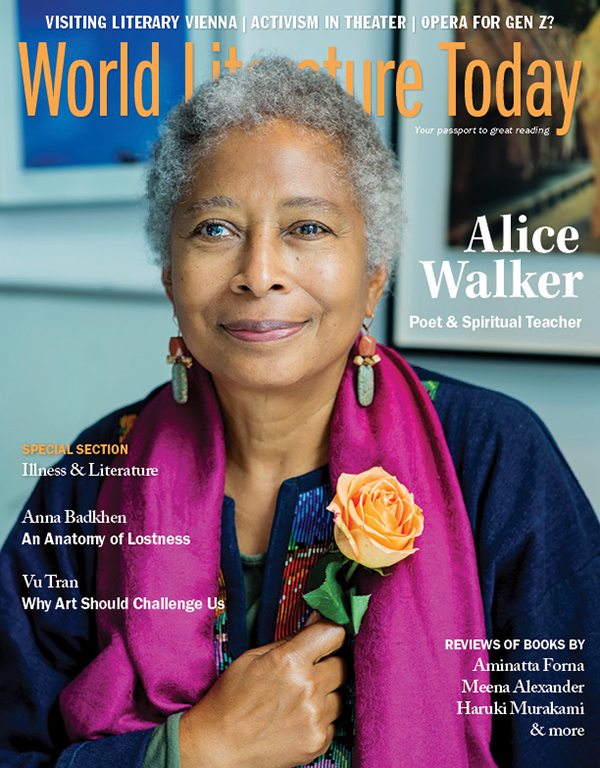

An Army of Spiritual Teachers: A Conversation with Alice Walker

I’m sure it wasn’t coincidental, when I phoned Alice Walker at her northern California home in August, to find her gardening. Flowers are perhaps the most common motif in her fifty-year catalog of poetry, novels, and essays, illustrated by book titles like Revolutionary Petunias and There Is a Flower at the Tip of My Nose Smelling Me. Walker’s writing, and Walker herself, have evolved over the years toward greater simplicity and elemental pleasures—turning earth and meditation. The poems in her recently released volume, Taking the Arrow out of the Heart (Atria Books, 2018), favor straightforward language and everyday speech over figurative device and adventurous diction. But the emotional landscape is conflicted and turbulent, often depicting racial wounds and global violence. One poem portraying an unidentified mass brutality begins by pairing the pretty and the profane—“They will always be more beautiful than you the ones you are killing”—and ends with a searing “Selfie this.” Earth herself suffers perhaps the deepest wound for Walker. We have limited time, she warns, but reminds us that tending poems and flowers can heal.

Erik Gleibermann: Alice, I’m not surprised you’re in the garden. And that’s good because there are flowers in this poem I picked out to start (“We Never Were Without Help”). I picked it because it has both revolution and flowers, and my favorite poetry volume of yours happens to be Revolutionary Petunias.

Alice Walker: Let’s talk about Celia Sánchez. This poem was dedicated to her for a reason. Celia herself was a great gardener. If I ever go back to Cuba, and I hope I do, I want to visit her house, where I hope they still have her garden flourishing. Without Celia Sánchez the revolution probably would not have happened and flourished the way it did. She had a very strong will yet was very self-deprecating. She didn’t push herself forward the way the men did. The poem is in praise of her courage and integrity as a person and a woman. They wouldn’t listen to a woman. One of the things I love about her is her strong friendship with Fidel, who could listen to a woman and loved her very much. People in revolutions die for us by living in a way that means our thriving. They keep going even if they fall. Her arms and the arms of other people like her are around us in what they leave. Their eye is always on that flower that is struggling, which is often us.

Gleibermann: One of the things that strikes me in this poem is that the speaker, who I don’t assume is you but seems like you, as they do almost all the time, says revolutionaries give their lives for the “flash of a vivid bougainvillea,” that a flower is so precious they would die for it.

Walker: It’s symbolic, and you do it for everyone.

Gleibermann: It seems like you hover between grief and celebration in these poems. The earth itself seems to be expressing grief and hope. I’m wondering how you see the balance of these things in your poetry at this time.

Walker: Well, it’s the same as I see them in the world. It’s wobbling toward its destruction and is in the midst of destruction anywhere you go, with war, fires, floods, and corrupt leadership. So, the grief is well earned by the life that we have and also the joy, if we are able to express it and have enough around us of sustenance to actually feel it. Many people are now so terrorized and so hungry and so destroyed that the joyous part is almost mythical to them. But in my life, I have been blessed to experience incredible grief and the joy that can sometimes be a relief from grief, even if it’s temporary.

Many people are now so terrorized and so hungry and so destroyed that the joyous part is almost mythical to them.

Gleibermann: Is the writing of poetry for you, and maybe the receiving of poetry, a balm against the grief or a means of working it through?

Walker: Oh, yes, it’s an absolute ladder out of the ditch or the well or out of the despair. I’ve been very grateful to have it my whole life. It’s not a decoration. It’s not just an idle passion. It’s cherished as something that is an expression of what is alive.

Gleibermann: Does any poem come to mind in the new collection that embodies that?

Walker: You could just open anywhere.

Gleibermann: You have a lot of odes and homages. One of my favorites is “My 12-12-12.” I actually don’t know what that title means.

Walker: It’s the 12th month, the 12th day of 2012. The 12th of December is the day we celebrate the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico.

Gleibermann: It has a sense of mystery in it. This young woman becomes the Virgin of Guadalupe. Maybe you could reflect on her.

Walker: It’s really pretty straightforward. I’ve lived in Mexico now for most winters for many years. And the poem is about really feeling myself there, knowing where I am and knowing when the river is high and when it’s low, knowing when the celebration of the Virgin is going to happen, knowing whether the nun is going to sing well, reflecting on the beauty of being there and being part of that ritual, which I try to be in every year, even though I’m not into the nuns and the priests because Catholicism has been so injurious to the indigenous people.

Gleibermann: It makes me think about the feminine energy, the womanist energy in your writing over the years, and how maybe the Virgin of Guadalupe is another manifestation of that healing energy.

Walker: What I like about her is that she is theirs. Catholicism basically enslaved the people. An indigenous man had a vision and she appeared, which meant that people in that part of the world, Mexico and other countries, don’t have to rely on the Virgin Mary. She’s brown like them and she has hair like them. She has a heart like theirs. But I notice that even this late in the day, they still cannot have a procession without a cross. The Catholic Church is so jealous of anyone seeming to usurp their authority that they make them carry a cross along with the Virgin, and it’s so grotesque. But the poem is joyful about finally not being in the frame of something. I feel like I’m out of the frame when I’m there in the road.

Gleibermann: One of the things that struck me as I read the poem is that there is a lot of movement. It’s like you’re taking a journey or we’re taking a journey along with her. There’s a very free feeling to it. But let’s switch to something different, to the Martin homage. You have more than one poem that speaks about Dr. King. You called this one “The New Dark Ages.”

Walker: We’re in a dark age.

Gleibermann: Do you see us in a darker age more recently?

Walker: Of course. It’s an extremely dark age for all kinds of reasons. You just wonder how long it will take to awaken. It’s incredible how long it takes for people to realize they are really being harmed.

Gleibermann: The question that came to my mind when I read “The New Dark Ages” was if he read your poem and he were here today in this dark age, what would he say or what would you talk about?

Walker: One thought that I have had over the years is that people who love us and sacrifice so much for us like Martin and Malcolm X and Celia Sánchez, before they wear themselves out, they should just drop everything and go somewhere else and retool themselves. My model for that is Bob Moses, who was incredibly loved and venerated in the Civil Rights movement in Mississippi. He realized he was becoming almost deified, and he didn’t want it. He understood that was dangerous, so he just dropped it and went to Tanzania. And then he reinvented himself to teach high school algebra. So, that’s what I would like to talk to all these people about, who have given so much to us and lost their lives and had great unhappiness.

Gleibermann: It raises the question of taking care of your individual life but then being dedicated to a cause. That brings us back to the Celia Sánchez poem at the beginning, giving my life for the flowers but understanding I’m going to be a martyr. I know that, but I’m going to do it anyway. That’s my path. It seems like a hard struggle, a hard choice to make. We can burn ourselves out staying devoted to what we believe in, even though we know it’s a potential losing battle.

Walker: But you have to remember that these are very special beings and they did come here with a purpose. Most of them knew that fairly early on.

Gleibermann: Over the years you’ve been asked about your idea of God. You’ve often talked about the earth, the body of earth, “Her Blue Body Everything We Know,” mother earth. When you talk about that, because of the earth’s destruction we are facing, it must be particularly painful, and that comes out in many of the poems.

Walker: It should be for everyone. And the question is why are people so numb? I think they are awakening, and I’m very happy about that. But awakening has been so slow. And that’s the dark age. People are having a hard time gaining knowledge and wisdom. The educational systems are completely unreliable and full of land mines for most people. So, yes, it is a dark age, and you can only hope people will come out of it, but they have to turn off gadgets and start to talk to people. And the time is very short.

So, yes, it is a dark age, and you can only hope people will come out of it, but they have to turn off gadgets and start to talk to people. And the time is very short.

Gleibermann: Can poetry and literature awaken us?

Walker: It’s awakened me. That is our hope, that our artists can. It’s almost as if our people who write and paint and dance and sing and love us are a kind of army in themselves of spiritual teachers. And meditation. The whole point of the book is to share the sorrow of the world but also the good news that we are not without medicina. The sorrow is always there, but we can train to be fairly staunch, looking at the earth and the trees.

Gleibermann: Who do you look to these days—writers, but you also mentioned other kinds of artists—to inspire you or to awaken you?

Walker: There’s the Nigerian Chigozie Obioma who wrote The Fishermen. There are many Nigerian writers who are amazing. I don’t understand it.

Gleibermann: So many of them follow in the Chinua Achebe tradition.

Walker: That’s the only person people know. The system latches on to one person of color and then they streamline everyone into that role. But that’s too narrow. Recently, I also like the Irish writer Joseph O’Connor who wrote Star of the Sea. Then there’s Tayari Jones, who wrote An American Marriage. And Queen Sugar, by Ava DuVernay, is one of the best things on television.

Gleibermann: I’ve seen both seasons of Queen Sugar, and it’s a situation where characters derive their spiritual energies from the land and returning to the land that now is threatened.

Walker: The love of the land is indigenous. Most African Americans are also indigenous. So, the land is very crucial to how we think about everything. It’s good to have someone with that same sense on television, though that sense is still not enough in my opinion. If I have one critique, it’s that they don’t honor the land itself as earth enough.

It’s awakened me. That is our hope, that our artists can. It’s almost as if our people who write and paint and dance and sing and love us are a kind of army in themselves of spiritual teachers.

Gleibermann: Do you think we need to be shot in the heart as well as having the arrow taken out?

Walker: Well, it’s not a matter of whether we need it. It’s just inevitable. If you show me someone who’s never been shot in the heart with whatever arrow, I will show you someone who’s not really even alive.

Gleibermann: Does maybe being shot open our hearts?

Walker: It’s hard to learn this, especially as a younger person. You feel singled out and that this is something which happens to other people and not to you. And then you realize it happens to everybody. One thing I said in the foreword to the book is that the drug industry is so glad we don’t know how to remove the arrow, which says you don’t need to remove it, just numb your heart.

Gleibermann: When you talk about meditation as a key for the healing, I think about the relationship between poetry and meditation. Your poetry seems to have become like meditation. It has a stripped-down quality, I mean bare, essential language going all the way back to Once. Your poetry is very straightforward in many ways.

Walker: Because my root teachers are Bashō and Issa, and in this country, Emily Dickinson, who was never verbose. I really have a fondness for what is simple.

Gleibermann: The language of your poetry is simpler now.

Walker: I don’t want to burden the poem with something it doesn’t need, just to prove that I can.

August 2018

Read an excerpt from Alice Walker's "12/12/12" from this same issue.