On Fire: Five Meditations on Opera

During a 1969 trip to India, composer Philip Glass was compelled to learn more about Mahatma Gandhi and eventually created Satyagraha, the second work in his Portrait Trilogy. Is Satyagraha now the opera able to attract younger and diverse US audiences? Kevin Simmonds argues that given the current erosion of truth, its promise to do so is exceptional.

1

WHETHER IT'S DUE to social flattening (and the subsequent widespread aversion to historically elitist institutions) or generational lapses in classical education, there seems to be little question that opera has the odds stacked against it when courting Generation Z, Millennials, and even their Generation X elders. Despite companies routinely employing strategies such as sex-lite marketing campaigns, movie theater simulcasts, big-name collaborations (touted as “innovative”), and lavish new productions, I doubt American opera companies can make the four-hundred-year-old form appear hip enough to induce FOMO in younger audiences. Even Peter Gelb, general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, has famously said that he’s up against the “cultural and social rejection of opera as an art form” and that “grand opera is a kind of dinosaur of an art form.” Gelb is right. But I wonder if he and his peers know they are partly to blame. I mean, this is a terribly unadventurous group.

While it’s true that companies must get younger audiences into their houses if they’re to survive, they are infamously conservative, careful not to upset their base—the grand and great-grandparents of Generation Z. So it’s always the standard offerings of Mozart, Rossini, Puccini, and Verdi that are first to receive makeovers (those “innovative” and lavish new productions I mentioned earlier). But therein lies the problem. Makeovers won’t do. Opera companies need to produce new operas. Brand-new. “New” connotes “now,” and, despite its intrinsic drawing power for younger audiences, who are ever interested in the latest thing, “new” remains a gamble for dyed-in-the-wool companies and their subscribers. Companies, even those with multimillion-dollar budgets, aren’t putting a fraction of their full weight behind new operas.

2

THE 2018-19 SEASON of the leading US companies (Chicago Lyric, Houston Grand, the Metropolitan, San Francisco, Santa Fe, Seattle Opera, and Los Angeles) bears this out. Depending on how you count, no more than ten operas (out of roughly sixty-six) could be considered new or fairly contemporary (from, say, the last fifty or sixty years, which some would argue stretches the seams of “contemporary”). I’ve excluded the old but quintessentially thought-of-as “newish” workhorses Porgy and Bess, Dialogues of the Carmelites, and The Turn of the Screw, all of which would require me to reach back to 1935, 1953, and 1954, respectively. While smaller niche companies and music schools may be mounting dozens of newer works, it’s doubtful those efforts gain traction nationally for such works at top-tier houses. The Met and other leading companies must take the lead.

While anyone who’s experienced the sublimity of live opera would be grateful for any operatic offering (and here in the US we’re lucky: there are thousands of performances annually), many, like me, would be ecstatic if they could hear recent works, works that explicitly address living in this century. Rigoletto, Elektra, Don Giovanni, Carmen, and La Bohème consider age-old questions about the human condition, but, for younger audiences, I’d bet Seattle Opera’s offering of The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs or Santa Fe Opera’s Doctor Atomic are generally more relatable and relevant to their day-to-day lives.

When I asked him about this, Jake Heggie, composer of operas such as Dead Man Walking and It’s a Wonderful Life, had this to say:

Composers have always sought out subjects that interest, resonate, and fascinate the audiences of their time. Something with a sense of familiarity to draw them into the theater without wondering “what is that story,” but curious to know “how will they do that story?” Early on, it was myths and legends about gods and goddesses vs. mortals—a quest for understanding identity and dealing with one’s lot in life. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, composers turned to plays about royalty vs. the common people and rich vs. poor—ongoing struggles for power, control, and, again, identity. Since then, composers have also turned to stories of the day, newspaper serials, headline news, popular books, movies, the internet, etc. Always on the lookout for what will resonate with audiences young and old to bring them into the theater.

What are the chances that an opera sung in Sanskrit (drawn from the Bhagavad Gita) and written in 1979 is the kind of opera younger audiences want to experience right now?

So what are the chances that an opera sung in Sanskrit (drawn from the Bhagavad Gita) and written in 1979 is the kind of opera younger audiences want to experience right now? More than that, what if this now middle-aged work exemplifies how new opera—typically innocuous and rarely, if ever, politically daring—convenes and conveys the interconnectedness of all people while also exploring various marginalized groups and the interlocking forces of power oppressing them? An opera that is intersectional in its subject matter? Satyagraha, by spry eighty-one-year-old composer Philip Glass, could very well provide a template to attract more diverse audiences for woefully out-of-touch opera companies. According to Heggie, “Satyagraha is right in line historically: a beautiful, engaging, fascinating opera about a hero who has entered modern mythology: Gandhi.”

3

ON MY WAY TO the Vanderbilt Holiday Inn shortly after picking him up from the Nashville airport one afternoon my senior year in college, I asked Philip Glass, who was to give a solo piano recital that night, if he’d composed any vocal music. Yes, some. You should look it up. More than twenty years later at a San Francisco bookstore where I sold him a copy of the New York Times, I reminded him of my youthful ignorance and that I had, indeed, looked it up. When I’d asked him that embarrassing question—doubly so because I’d been a music major concentrating in vocal studies at the time—he’d already composed fifteen operas, and he is now peerless among living American composers, having witnessed the performances of his twenty-five operas that span forty-two years. Of course, while prolific in film, orchestral, and chamber genres, he is arguably America’s preeminent opera composer, whose own distinct compositional sound—generally speaking, a minimalist looping of a fundamentally tonal language working through sudden or unexpected shifts between major and minor keys—has exerted considerable influence on the basic sonic properties of contemporary American opera.

A self-proclaimed student and practitioner of four traditions, which he discusses throughout his 2015 memoir Words Without Music, Glass is, himself, a driven truth seeker. For nearly sixty years, his “Four Paths” have been Hatha yoga, Tibetan Mahayana Buddhism, Taoist qigong and tai chi, and the Toltec tradition of central Mexico. His musical oeuvre has grown from this. Satyagraha, about Mahatma Gandhi, is the second in his Portrait Trilogy (between Einstein on the Beach and Akhnaten) depicting men who have changed the world. The three acts of Satyagraha represent past, present, and future, and each is presided over by a noted figure (Leo Tolstoy, Rabindranath Tagore, and Martin Luther King Jr., respectively). These figures link and embody the continuum of truth seeking.

The music is quintessential Glass: unyieldingly repetitive rhythmically, harmonically, and melodically—no doubt daunting for ears attuned to opera’s conventional dramatic and musical pacing and development. Conductor and flutist Ransom Wilson has famously spoken about how this struck him at the 1976 premiere of Glass’s groundbreaking opera Einstein on the Beach:

As I listened to that five-hour performance, I experienced an amazing transformation. At first I was bored—very bored. The music seemed to have no direction, almost giving the impression of a gigantic phonograph with a stuck needle. I was first irritated and then angry that I’d been taken in by this crazy composer who obviously doted on repetition. I thought of leaving. Then, with no conscious awareness, I crossed a threshold and found that the music was touching me, carrying me with it. I began to perceive within it a whole world where change happens so slowly and carefully that each new harmony or rhythmic addition or subtraction seemed monumental.

This year, LA Opera and Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) are presenting Satyagraha. Staging Satyagraha now, on both coasts, is timely and telling. Perhaps more important, it could be a course corrector for opera companies. It was visionary when it debuted and remains so today. Not just because of the ambition of its musical language and tableau form but also because of its timeless and universal themes. The work offers a meditation on the concept of satyagraha, which is variously translated as truth force or truth insistence or truth firmness.

Glass traces the genesis of Satyagraha to a 1969 trip to India, when a rug dealer he’d recently befriended arranged a screening of news footage of the 1930 Salt March. In a village movie house, Glass saw, for the first time, Gandhi and the throngs of thousands around him dipping the fabric of their dhotis into the ocean to harvest salt in peaceful protest of the salt tax imposed by the British Raj. He was so moved by Gandhi—“the stamina of his morality, the courage of his ideas”—that he was “on fire” to learn more about his life and legacy.

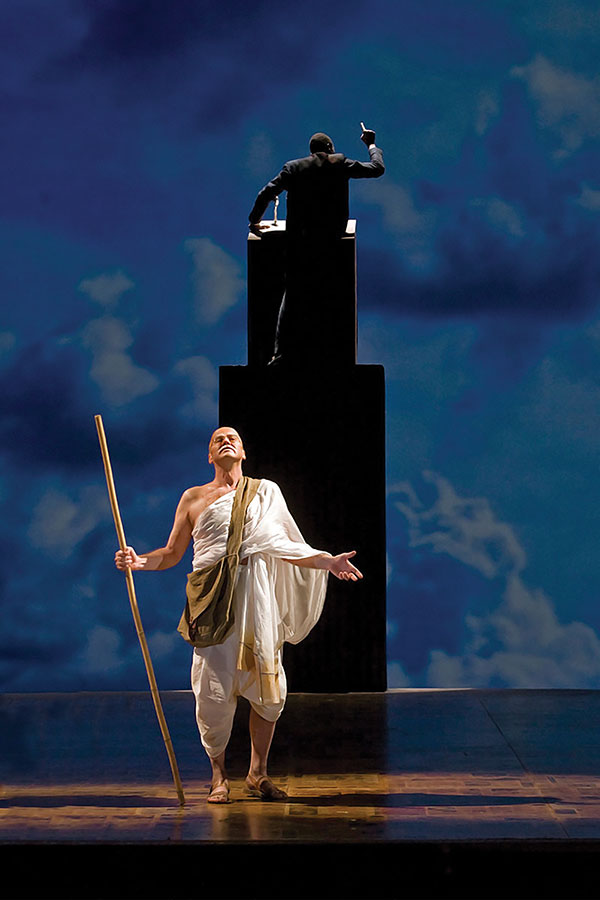

Photo: Ken Howard/Courtesy of LA Opera

4

GIVEN THE EROSION OF TRUTH in our nation right now, the promise Satyagraha has to draw young and diverse audiences is exceptional. Bora Yoon underscored this when I asked for her thoughts about the opera. Composer of the opera Sunken Cathedral and considered an important voice in contemporary opera, she had this to say about the Met’s 2011 production:

I was heartened by the relevancy audiences found resonant with the political climate, its call to action, and vehicle to cohese a community—as art’s job is to respond to the times (and, ideally, galvanize critical dialogue that would not happen otherwise without the medium of art). There is much to be gleaned from the revival of operas, and the labor of creators, designers, and directors who thread that relevancy to our times, and I hope to see more of it, considering operas are usually based on narratives in history (which I find problematic in representing POC in an empowering way that is not indentured or exotifying), but operas such as Satyagraha give me hope when it is an epic told in a way that is representative of the times.

In Satyagraha, one beholds an indivisible work that, according to former Washington Post music critic Tim Page, is marked by “spiritual propulsion and radiant intensity . . . closer to ritual than entertainment, to the mystery plays of the Middle Ages than to standard opera.” The relentless rhythms embody—somehow—the loftier calling of Satyagraha, confirming—somehow—Glass’s own personal quest to discover truth and, for all our benefit, deploy its sound. I was heartened by the relevancy audiences found resonant with the political climate, its call to action, and vehicle to cohese a community—as art’s job is to respond to the times (and, ideally, galvanize critical dialogue that would not happen otherwise without the medium of art). There is much to be gleaned from the revival of operas, and the labor of creators, designers, and directors who thread that relevancy to our times, and I hope to see more of it, considering operas are usually based on narratives in history (which I find problematic in representing POC in an empowering way that is not indentured or exotifying), but operas such as Satyagraha give me hope when it is an epic told in a way that is representative of the times.

Given the erosion of truth in our nation right now, the promise Satyagraha has to draw young and diverse audiences is exceptional.

5

EVEN AS AN IMPRESSIONABLE college student, I’d been taken by Glass’s humility. Since then, given my work in the arts, I’ve met a wide sampling of the world’s most celebrated artists and thinkers. Very few made me feel as comfortable and seen. It wasn’t until my inteview with Tania León, composer of the operas Scourge of Hyacinths and Little Rock Nine, however, that I began to apprehend the lived interpersonal expression of Glass’s convictions, convictions to which I could personally attest.

Simmonds: I especially appreciate your illuminating something I hadn’t thought as deeply about as it pertains to Glass and his practice as a Buddhist. Perhaps we can attribute some of the widespread success of his work to this practice.

León: Of course! He does [the Tibet House US Benefit Concert] at Carnegie Hall every year to collect money for the people of Tibet. And you have to see the display of artists who come—people from every walk of life are on one stage donating their time for that cause—because he associates himself with everybody. And that’s the beauty of Philip. I admired that in him from day one. . . . Philip goes to Brazil, he’s a Brazilian. He goes to India, he’s Indian. He transforms himself everywhere he goes and is always kind to everybody. [His Buddhist practice] is why he’s attracted to Gandhi and all those incredible minds and philosophers, which, in a way, advocate universality and accessibility.

Echoing composer Bora Yoon’s sentiment, León also talked about the quality of racial and ethnic representation on opera stages as well as the lack of representation within the ranks of performance rosters and the company adminstrations themselves—all of which inevitably color the perception of prospective opera audiences. León, however, is optimistic, saying, “What an opera is today is what people would do in the villages,” and as such, younger and more diverse audiences will come if they see themselves reflected in the stories and in the performances. After all, she says, “the arts belong to the people.”

I understand her sentiment. I do. Yet from what I know of opera’s beginnings in Italy, it wasn’t exactly for the people. It was for some people, namely the wealthy and educated. And, one could argue, in many respects, that persists. I have no quarrel with that. But when an opera like Satyagraha comes along, I marvel at how an earnest composer-seeker—speculating on how to reverberate a revealed truth, evangelize it even—elevates the form as well as the witnessing audience. We not only find ourselves moved by the sound and the action on stage—a majesty unto itself—but we also find ourselves in the sound. That complex and clarifying experience is sure to ignite us too.

San Francisco