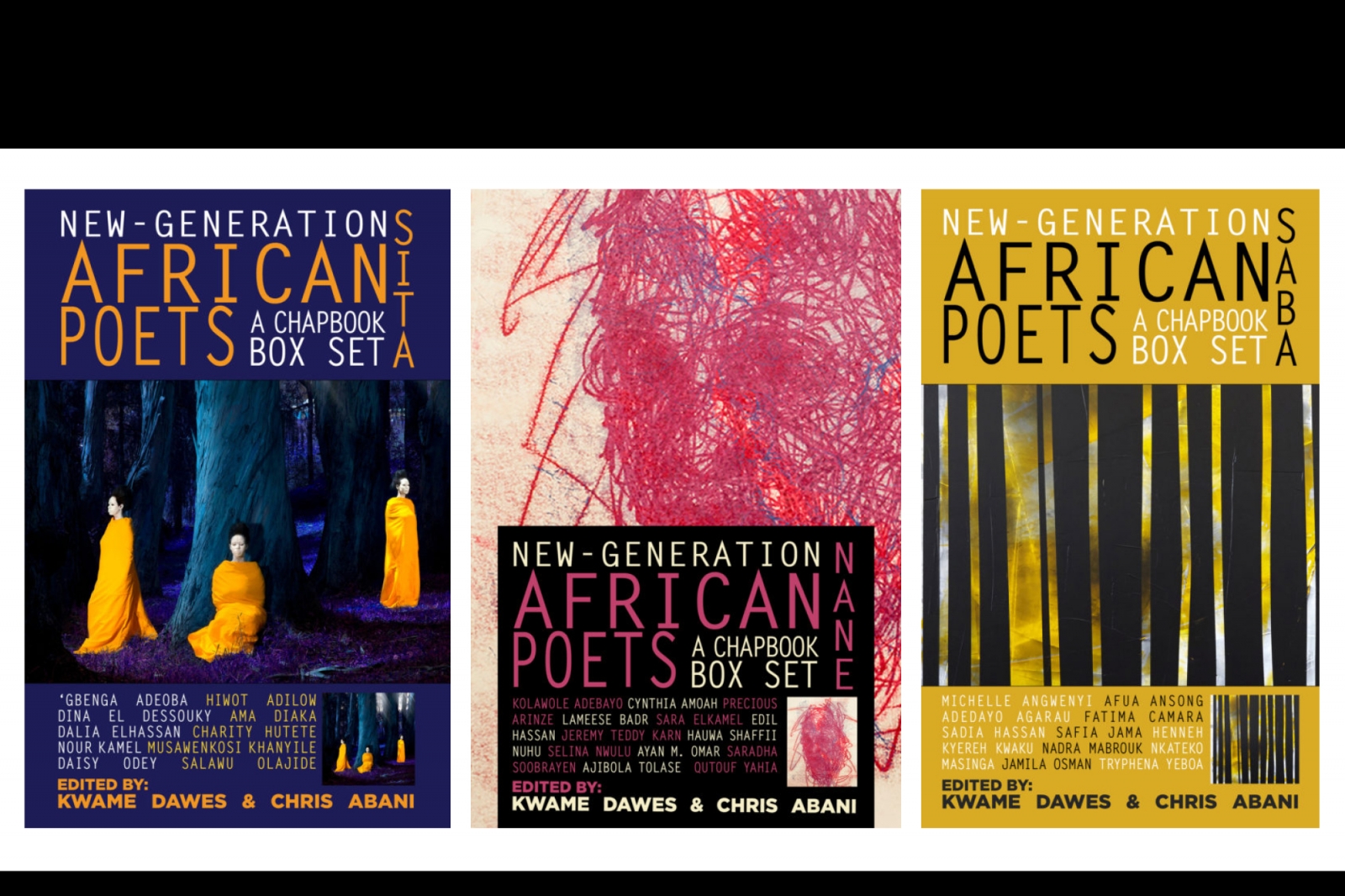

The State of the African Poetry Book Fund: A Conversation with Chris Abani and Kwame Dawes

The African Poetry Book Fund (APBF) promotes and advances the development and publication of the poetic arts through its book series, contests, workshops, and seminars, and through its collaborations with publishers, festivals, booking agents, colleges, universities, conferences, and all other entities that share an interest in the poetic arts of Africa. To date, the New-Generation African Poets Chapbook Box Set has published about one hundred new poets from Africa and the African diaspora. Nane, the latest box set, is out now from Akashic Books. In the following exchange, Erik Gleibermann engages the series co-editors, Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani.

Erik Gleibermann: Let’s start with the project’s overall vision of African poetry. Beyond the literal continental geography, are there common themes or threads you are discovering or seeking out that characterize African poetry for the APBF?

Kwame Dawes: The African Poetry Book Fund is a service. Our goal is to promote African poetry and African poets through multiple projects that include our publishing efforts. The project would not exist if there was not a massive failure to do this work for African poetry in the world. We set out to publish African poets, to celebrate and honor the history of African poetry, to engender the study of African poetry, to create a community for African poets in which they can be affirmed and supported in their work, and to create a space in which African poets can continue to thrive. We always began with the understanding that African poetry is a long and complex tradition, and that Africa, as a continent and as a concept, has been forged out of both the negative forces of colonialism and imperialism and by the process of solidarity and strategic collaboration, to somehow resist the collective efforts of Europeans to exploit and demean Africa.

So, Africa is not one thing. Africa is many languages many cultures, many countries, many states, many tribes, many histories, many faiths, many imaginations, millions and millions. So, you can imagine how impossible it is for me to begin to answer the question, “What characterizes African poetry?” If you were honest, you would agree that this is not a question you would pose about European poetry. And were I honest, I would concede that we gave you small license because we have embraced the label. However, you will also know that neither Chris nor myself has ever sought to characterize African poetry, except to say that people in Africa and from Africa are writing poetry, and this poetry is compelling and transformative and relevant, and it deserves to be shared with the world and with Africans.

Chris Abani: Kwame has answered this question so clearly and holistically that there is little to add to it. But I will throw out a challenge to whoever is reading this interview to resist the urge to let the questions, or our answers, offer little beyond an indicator that poetry is being written today on the continent by Africans or in the diaspora that has its roots deep in that continental culture and history with as much contemporary and global resonance and familiarity as that written anywhere in this moment by anyone. The challenge is to procure the books and read them. In the end that is the best measure. The work itself.

Gleibermann: Kwame, in the introduction to the most recent chapbook you mention the theme of movement and migration, writing that, “The superficial ‘borders’ that separate our worlds are more porous because we are traveling more, and we are connecting across all sorts of forms of media in unprecedented ways.” Is this fluidity, and perhaps the greater accessibility African poets have to one another online, shaping the identity of poetry across the continent?

One of the exciting developments in the work of APBF is that it is allowing poets from all over Africa to read the work of poets from all over Africa.

Dawes: Chris Abani has long reminded us that one of the exciting developments in the work of APBF is that it is allowing poets from all over Africa to read the work of poets from all over Africa. This is a function of publishing. It is a function of the use of social media. It is the function of technology, in other words. But the impulse is not new at all. We did not invent this. Africans have been finding common ground for centuries, and the forces that have led to this have varied season after season.

In the twentieth century, the growing desire for political and economic independence from the yoke of colonialism drew Africans together to seek common ground and understanding in their efforts to decolonize their continent. Among those who came together were the artists, the griots, the singers and writers, and dramatists, all of them meeting at conferences, at universities in Africa and in the West, and through their published work. As much as writers sought to capture their sense of self, their philosophies, intellectual prowess, and conceptions of beauty for their tribes and nations, they were finding great conversation with artists from all over Africa and its diaspora. The Heinemann series was very instrumental in helping to facilitate this conversation, this seeing of each other.

Whenever technology has failed, whenever the modes to communicate have been undermined, this dialogue has faltered. In poetry, this was an acute problem, and the APBF has sought to restore the space for this dialogue along with many organizations in Africa and around the world, like the Badilisha Poetry X-change, or Brittle Paper, or the multiple African festivals that have continued to emerge despite the challenges. So the fact that the poets are reading each other, meeting each other, and being influenced by each other is not surprising, and it is something that is hugely important. What we do is give them one key object in that conversation, the published poems, beautifully curated, lovingly encouraged, and promoted as best as we are able to.

Abani: Sometimes, tracking literary histories, pathways, and networks when it comes to the continent can feel like an endless reinscribing of things that have only vanished because of neglect. Consistency is the biggest difficulty we find at the root of this, or rather, the lack thereof. Kwame has pointed to the ways in which we are the new kids on the block in a long history of interventions. This fact is both instructive and anxiety-producing. We are always addressing this with the plan of creating wider networks of editors and invested parties, not only in poetry itself but in translation, common scholarship, and the other support systems such that this can pass on generationally and outlive us and even outlive the African Poetry Book Fund. We must find ways to keep this going. We welcome thoughts, volunteers, donations, and all the help we can get to ensure this work continues.

Gleibermann: Could you walk readers through the editorial process of working with a poet on a chapbook for your annual box sets? I’m particularly interested in knowing about any distinctive approaches to the editorial process that reflect the particular literary values of the APBF? Maybe you could highlight Saba and one of its poets.

Dawes: The process is quite ordinary. The remarkable thing is that it exists. Each year, we reach out to a well-developed and growing army of recommenders that includes poets, festival organizers, intellectuals, editors, literary prize organizers and judges, publishers, literary activists, and critics from all over Africa and outside of Africa, all of whom have a proven record of interest and awareness of what is happening in the poetry world. We invite them to recommend any poet that fits the basic criteria for eligibility for the chapbook series.

Once those recommendations are in, we do some research into the work of these writers (the internet helps a great deal) and start to narrow down a list based on eligibility, the quality of the work we can see, and the strength of the recommendation of the people we ask. Typically, that will allow us to form a list of sixty or seventy poets. We then contact the poets and invite them to submit a chapbook manuscript. The turnover time is two weeks. Our intention is to meet poets who are ready for this process in terms of thinking seriously about publishing.

Once the manuscripts come in, we read each one and make notes on them. Then we start a slow process of narrowing it down to ten to twelve manuscripts. What follows is an intense period of editing with detailed notes, suggestions, and so on to create a strong and representative collection. It is impossible to speak of that process in general terms as it is different with each manuscript. We have found that the poets are enthusiastic about getting intense attention for their work, and our goal is always to ensure that the chapbook is one that pleases them. Almost always, editing is about understanding what a poet is doing, and doing everything to help them do it better. Our wide understanding of poetry, our openness to see fresh and original work, and our confidence in the poetic and visionary power of these artists are elements that guide how we tackle these works.

I sense that you are wondering if there is something about African poetry that affects what we do. The answer is no. Many editors fail because they do not have a good enough grasp of the poetic traditions and influences that are guiding the poets they are editing. This is a universal truth. We are a good team—we have been doing this for a long time, and we have command of the varied and complex poetic, cultural, and intellectual worlds of these poets. But we are also keen to discover, to learn, to observe the ways in which these poets push themselves and push their poetics.

Our wide understanding of poetry, our openness to see fresh and original work, and our confidence in the poetic and visionary power of these artists are elements that guide how we tackle these works.

Abani: There is little to add here. Kwame may have said everything well. We have no personal agendas, minimize our personal filters, and trust the rigor of the process.

Gleibermann: There is a wide variety of established and emerging literary publications centered on new African literature, such as Lolwe, Jalada, and Brittle Paper. How do you connect with these publications to discover, cultivate, and promote writers you may want to publish?

Dawes: We read them, we stay in touch with them, and we seek recommendations from them for new writers. But we also try to use those avenues to get word out about what we are doing and what services we have for poets. In the long run, if what we are doing can engender enough interest to ensure that more and more such entities are created, then we will be doing the right thing. For the record, there is still a dearth of such outfits, and many struggle to stay afloat. We believe that the work we are doing is predicated on the commitment to help sustain these outfits. We have seen many Western journals and publishers publishing the poets we first published in the chapbook series or as part of our contests, and we welcome and celebrate this. This was part of the design.

Gleibermann: MFA programs increasingly seem to be platforms for poets to get traction. Do you work with MFA programs as incubators for emerging African writers?

Dawes: African poets know what they are doing. They pay attention to what is happening in the literary world. The internet has given them greater access to information about such programs. But more importantly, many of these institutions are filled with people who have been doubtful about the existence of African poetry, and this is because for decades, the publication of African poets has been very sparse and limited. In the last six years APBF has published over one hundred African poets. This has played a significant role in granting credibility and visibility to the quality of poetry that is being written by African poets. And this has made it increasingly possible for the poets to secure places in such programs.

None of this is easy. Studying abroad, under stringent and sometimes arduous immigration restrictions on students, can be difficult, and working in environments where teachers may have limited knowledge of the work of African writers can be challenging. But it has been a joy to see that more and more programs are welcoming African writers. We believe that we are playing a significant part in that. I suppose the effect is similar to what we have seen happening with journals and publishers that are now publishing more African poets. We understood that simple and basic access to well-edited, well-designed, and effectively presented work by poets in Africa and in the diaspora would begin to familiarize publishers and journals in the US with the rich range of African poetry. This has happened. We hope it will continue to happen.

Finally, I should say that the APBF editorial teams are all well-positioned and highly regarded writers around the world, and their letters of recommendation have, no doubt, played a major role in facilitating this development. Further, we have, by inviting poets to write forewords for each of the chapbooks, essentially opened a dialogue among African poets and between African poets and poets in the UK and America. We encourage a savvy and supportive approach to the advancing of the careers and the training of poets who come within our purview.

Abani: Much of the learning of essential skills and craft in advanced studies and in practical life for Africans both continentally and in the diaspora has been within the power of community. What do I mean? We can look to West African contemporary patterns of learning by communities of immigration to extrapolate a larger picture. Through various community networks, churches for instance, recent West African immigrants to the country are exposed to learning vital skills for integration. Community members help new arrivals learn new skills, point them toward jobs, provide networks of reference letters, and so forth.

It is no different in poetry. These poets help one another. They find books, they share books, they share ideas, they workshop each other informally, and they study the successful poets from those communities and model their work on that. Where I think MFA and PhD programs come into all this is that they become the “finishing schools” for African poets lucky enough to find themselves in those institutions. Those institutions provide not only the final skills necessary to create a large and lasting aesthetic, they also provide networks of opportunities among peer groups and, possibly, mentors to peer groups, all within the larger world of publishing, teaching, and making a life in the arts.

Gleibermann: How does the African Poetry Library Initiative work? What are ways to get poetry into the hands of African readers?

Dawes: The African Poetry Library was developed for African poets, and this remains our primary goal. Like much of what we do, it emerged out of a need. Many poets shared that one of their challenges was having access to a strong body of poetry—any poetry, but especially contemporary poetry. The challenges in many cities in Africa to sustain library systems with new acquisitions led, in many instances, to a significant reduction in the acquiring of contemporary books for readers. We decided to start the libraries through a partnership with organizations that serve writers in various cities on the continent. We supply the books, the cataloging, and serve in a consultative and supportive capacity with the people in these cities who are setting up and running the library. It is a partnership, but the bulk of the work has to be done by the organizations and individuals who are running these libraries because they are the ones who understand best how to serve their community. We will continue to create these libraries where the needs and the resources can be found in those communities to sustain the libraries. In the meantime, we have found imaginative ways to acquire books (book prize contests, publishers, literary journals, and individuals) and have allocated the funds to ship these books to the different libraries.

This does not answer your second question, however. The matter of poetry book distribution and poetry book sales in African countries is a major challenge, and we are now seeking funding to expand a study into poetry book distribution in Africa, and the development of a white paper that explores the economic structures and the legal complexities of doing this kind of work. In two years, we hope to have a very sophisticated strategy to ensure channels of poetry book distribution across Africa.

In the meantime, we have been able to see our books carried by festivals and small bookstores. But none of this is satisfactory, and APBF wants to understand the problems better, and to use its access to imaginative and inventive skills to arrive at solutions that will work. And these solutions will hold under consideration the multiple ways in which “books” are consumed, exchanged, and preserved.

Gleibermann: How does the project work to preserve and archive a body of African poetry classics?

There are many uncollected, unknown, and unacknowledged “archives” of African poets, living and dead, that are in danger of being lost.

Dawes: Quite frankly, our classics series is barely scratching the surface of what has to be done. As we speak, there are many uncollected, unknown, and unacknowledged “archives” of African poets, living and dead, that are in danger of being lost. And this does not even take into account what has not even been studied and written about. At the same time, if I were to ask you how many collected-poems volumes by African poets you know, I am sure you would be hard-pressed to name any, and you would probably end up naming some of the poets we have published in the last few years. We believe that the work of curating collected works, critical work, and the work of digitizing existing “archives” that have not been preserved are all part of what our global and ambitious vision is for APBF.

We have just begun a series called On African Poetry that is publishing critical work, anthologies, memoirs, and other forms of work on African poetry. This work is critical to ensuring that African poetry is considered seriously and explored effectively. We have also started a new African Poetry Translation Series, which will expand the work we are doing translating poetry into English from African European languages and from indigenous African languages. This is a long-term project that we hope will allow us to expand our understanding of and knowledge of African poetry in ways that could transform what we know and think we know about poetry today. Finally, the African Poetry Digital Portal has already embarked on a major effort to ensure that we have access to African poetry that dates back into antiquity and that is equally engaged with the contemporary development of African poetry. We recently received a major grant from the Mellon Foundation to carry out this important work. This portal project is a collaborative effort involving libraries at the University of Cape Town, the University of Togo, the University of Ghana, the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge, and Northwestern University, the University of Michigan, and the Library of Congress, all working with the University of Nebraska, where we are based. This is a massive undertaking and an exciting one, but it is formed by a vision that says African poetry is worthy of this kind of study.

To be honest, this does not cover everything we are trying to do, and it certainly does not reflect all the work that is being done around the world, but your question made me think to share that we are approaching a major undertaking with energy and great collaboration. The APBF editorial teams are the source of our success and the reason why we are able to do this work. Our publishing efforts have been made possible because of faithful, professional, and enthusiastic partnerships with Akashic Books and the University of Nebraska Press. Also, the fact that APBF is based at the University of Nebraska in partnership with Prairie Schooner has allowed us to rely on the combined efforts of the Prairie Schooner and APBF teams to carry out quite a number of tasks.