Editor’s Note

With the current issue, World Literature Today wraps up its ninety-ninth year of continuous publication. Even as the excitement of WLT’s centennial shimmers on the horizon, I’m reminded that the previous nine editors of Books Abroad and WLT all operated in the relative stability of the post-Gutenberg half-millennium, during which print culture held sway as one of the great change agents of modernity. In the midst of what some regard as the twilight era of print’s primacy in the first quarter of the twenty-first century, the digital change agent on everybody’s mind, of course, is artificial intelligence. My editorial colleagues and I hope the cover feature that begins on page 23 will help WLT’s readers begin to reckon with the implications that AI has for world literature in 2025 and beyond.

One of the first reckonings to wrestle with is not just the natural vs. artificial debate, but what constitutes the oft-neglected second part of the phrase: intelligence. In the September 2025 issue of Harper’s, Meghan O’Gieblyn contends that most techno-utopians cling to a persistently “strange belief that intelligence and knowledge alone will lead, through some secret orthogenesis, to moral clarity.” Against this “scaling hypothesis” (“the belief that bigger models will produce more intelligent outputs”), O’Gieblyn counters with an emphasis on how ethical considerations—including what we might learn from human suffering—can lead to practical wisdom based on contextual understanding, “epistemic humility,” and empathy.

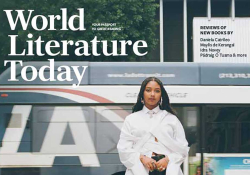

The work of Sasha Stiles, featured on this issue’s cover and leading off the special section inside, penetrates to the very heart of such questions. In her probing essay, “On Finding Language for What It Means to Be Alive Today,” Stiles argues that, instead of categorizing poetry as “the most human of arts and technology as its opposite,” a centuries-old continuity connects the two. “Like any tool or code,” Stiles writes, “poetry operates as an interface, carrying meaning across thresholds—and in the process, reshaping what is carried. . . . Poetry has always been a guide through uncertainty and change.” As a companion piece to A Living Poem, Stiles’s ongoing “poem in residence” show that opened at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art in September, her essay offers rich opportunities for reflection.

And when it comes to “carrying meaning across thresholds,” the test case of translation in the age of AI may be the most contentious fault line in contemporary world literature. While D. P. Snyder and Kenneth Kronenberg each make impassioned arguments on behalf of the enduring value that literary translators bring to expanding and enriching the field of world lit, Ilan Stavans—a prolific editor, publisher, and translator—also ranges widely, in his interview with Susan Smith Nash, in considering both the pitfalls (“AI is blunt, insipid, unworldly”) and the potentialities of AI. For Stavans (as for O’Gieblyn), beyond the hype of AI, the best translation practices are ultimately marked by discernment, that perennially human condition, which evolves from lived experience, hard-won judgment, and deep cultural knowledge.

Elsewhere in the issue, the stakes of translation become clear in Carol Rose Little’s essay describing her work as a Ch’ol interpreter in a federal courtroom a few miles north of the US–Mexico border (page 10). Interpreting for a man from Chiapas who pleads guilty to illegally entering the United States, Little draws on her academic training as a linguist but, more importantly, on her yearslong experience of having been immersed in Ch’ol communities. “To translate or interpret ethically,” she writes, “demands a fidelity that is not only linguistic but moral.” Bound up in the question of fidelity is a truth beyond denotation, when word-for-word equivalences between Ch’ol and English don’t exist. Summing up her dedication to this practice, Little writes: “When I interpret for someone in court or collaborate on translating a poem, I seek to bring a person into the room, a voice that might otherwise remain silenced. I do this work, not just to translate words, but to make space for someone to be heard, to understand, to feel less alone, and to ensure that the person speaking or writing is not muted and not silent.”

Intelligence with a deep ethos that promotes a rich variety of voices expressing both art and wisdom—we hope readers discover such intelligence on every page of WLT. And bringing readers the best of world literature will remain our mission for many years to come.

Daniel Simon