Editor’s Note

If WLT were not in existence,

we would have to invent it.

—Czesław Miłosz

A golden age of print culture managed to thrive during the depths of the global Great Depression, despite the economic constraints faced by many magazine publishers. WLT’s founding editor, Roy Temple House, surveyed the surfeit in a 1938 editor’s note that also lamented the “pathos,” in his words, of the short-lived nature of many of these publications:

We are sure that when Keith Preston wrote his famed quatrain about the little magazines [“Of all the literary scenes / Saddest this sight to me: / The graves of little magazines / Who died to make verse free”], there was a touch of sadness in his gentle satire. The passing of a magazine is a deeply tragic circumstance. For magazines and papers, all magazines and papers, are alive, some of them more than others, perhaps, but all of them wonderfully, touchingly, terribly alive. (BA, Spring 1938, 254)

Such aliveness—and ephemerality—was the hallmark of most little magazines during the modernist era. In the nineteenth century, the astonishing proliferation of global production and circulation networks had made newspapers and magazines so ubiquitous (and cheap) that, propelled by the benefits of public education, millions of new lower- and middle-class readers joined the ranks of the literate. These readers also benefited from newly acquired forms of knowledge and mobility, which allowed them to escape the provincialism that tethered individuals to their place of birth. As Linda K. Hughes writes in a review of Clare Pettitt’s magnificent recent books devoted to Victorian print culture, Serial Forms (2020) and Serial Revolutions 1848 (2022): “Enabled by print and technological materiality, time, and human experience and cognition, the serial became a new episteme—a new system of understanding, experience, and knowledge.”

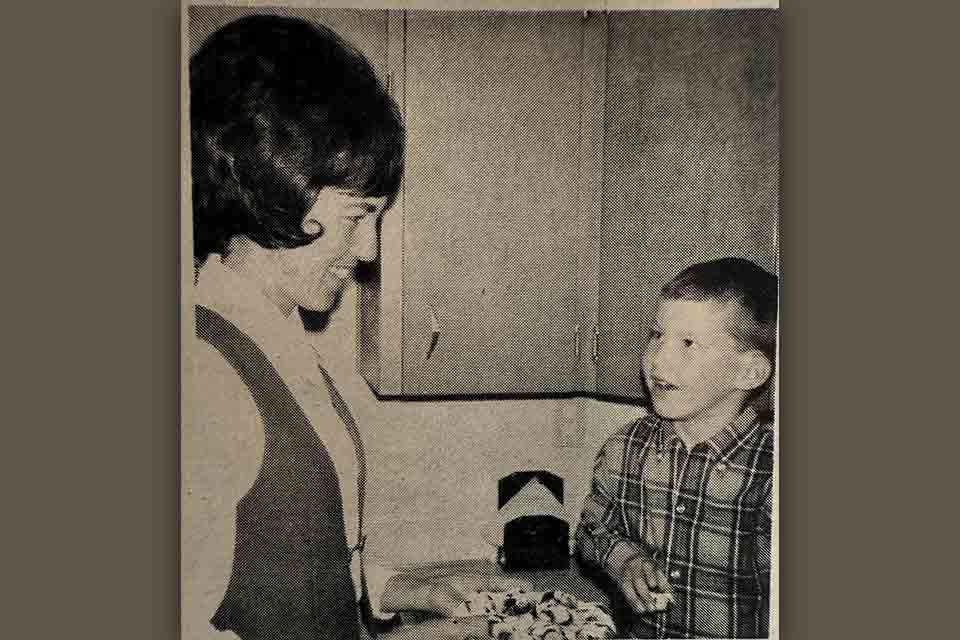

As a young boy growing up in the Midwest, I knew nothing about epistemes, but I was immersed in my Nebraska hometown’s serial print culture: my very first gainful employment involved delivering the weekly local newspaper on Thursdays after school and collecting subscriber payments. After going house to house on my bike, distributing the North Bend Eagle on the east side of town, I’d stop at the Widhelms’ hardware store for a candy bar or at Mrs. Bloch’s house for a Twinkie. The paper also gave me my first taste—literally and symbolically—of small-town celebrity. The Eagle’s “From the kitchen of . . .” column profiled local homemakers, and the grainy inset photo included here—taken when I was four years old and still small enough to sit on the kitchen counter—accompanied my mom’s recipe for chocolate crinkle cookies (May 6, 1971). It didn’t dawn on me at the time, but I was becoming a model citizen in the republic of consumption, on both the supply side and the demand side. I was also years away from editing a literary magazine, but issues of Boys’ Life and Field & Stream showed up in our mailbox on a regular basis, proof positive of the robust seriality of print culture in the 1970s and ’80s.

Decades later, as WLT begins its 100th year of continuous publication in 2026, I still have a weakness for chocolate—and the printed word—delivered on a regular basis. If you live anywhere in the US, it only costs fourteen cents a day to have the magazine appear in your mailbox every two months. Such dependable regularity, when so much about the world is unpredictable and evanescent, seems worth preserving for the next century. We are grateful to the many WLT readers and patrons—benefactors all—who believe in supporting our cause. And in the pages that follow, I hope readers will encounter a magazine “wonderfully, touchingly, terribly alive.”

Daniel Simon