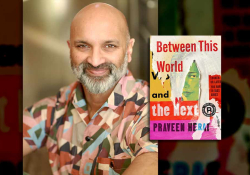

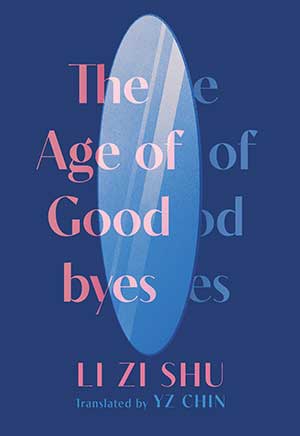

5 Questions for Li Zi Shu

Li Zi Shu is the author of the Taiwanese best-seller The Age of Goodbyes, now available in English translation by YZ Chin (Feminist Press, 2022).

Q

YZ Chin’s translation of The Age of Goodbyes is your first book available in English and the first time a novel by a Malaysian woman writer working in Chinese will appear in English. What do you make of these milestones?

A

A

As a matter of fact, there are very few novels you could find in Malaysian Chinese literature. The current environment has never been supportive. Not only that Chinese, as a language commonly used for generations in Malaysia, is not officially recognized, but our literature also has been marginalized in the Chinese-speaking world. For decades, Malaysian writers who work in Chinese have been struggling to survive on a small readership, low pay, and very limited space for publication. To work on novels is simply unrealistic. It is also true that the number of women writers was relatively small in the past, so it is not surprising that I could be the first Malaysian woman writer—after twenty-five years of my career—who gets her Chinese novel translated and published in English.

However, I must admit that I had never thought of expanding my readership beyond the Chinese-speaking world—not even to Malay readers, until YZ Chin, the translator of The Age of Goodbyes, brought up the suggestion. I and my peers in Malaysia who write in a marginalized language have worked so hard trying to be seen and recognized. I am glad and excited that my work could be the first step we take to go out into a wider literary world. Hopefully, it will draw the attention of more readers to Malaysian Chinese literature.

Q

You are known for daring experimentation with form. For instance, The Age of Goodbyes begins on page 513. Are there other writers who have inspired you in this regard, or are you working against what you’ve read?

A

I was considerably young at the time I wrote The Age of Goodbyes, and absolutely a beginner as a novelist. Like most young people, I was fond of exploring, easily fascinated by forms and techniques, and courageous enough to play with all kinds of perceptible, even tangible devices, such as formal and linguistic methods, in order to explore the possibilities of novel writing. Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino were my favorite writers; they still are. It was almost impossible for me to resist the charms of their works and not be influenced by their ideas of construction of human society and the world.

In fact, it was only after I finished The Age of Goodbyes and had learned from the experience that I began to gradually develop my own ideas of form. From the first novel to the second (Worldly Land), which came out two years ago, I had been pursuing—at a higher level, I believe—a new approach to fiction writing that is less formal and technical. Not that I care less about form now, I just think that I should be capable of integrating form into narrative, instead of using form to shape a novel and pouring narrative into it.

Q

Would you tell us a little about The Age of Goodbyes?

A

The novel was written in my late thirties. I was so determined to write a novel at that time. For many years before I had written only short stories, or flash stories, as they were easier to get published, and it was a quicker way for me to earn a living. Right before I turned forty, I decided to write a novel, setting it as a career challenge to explore more possibilities of fiction writing. I chose to tackle a subject I was most familiar with, which was the changes of the Chinese community in Malaysia. The story begins on May 13, 1969, the day an incident of ethnic conflict took place, namely the 513 incident (May 13 incident) in our history. Many people were killed and injured on that day. The incident had a significant impact on the democratic system and subsequent political situation in Malaysia. For years, 513 had been a taboo in our country, especially in the Chinese community. The novel uses a three-tiered narrative structure to bring out the incident and to talk about our—including my own—confusion over our identity, our search for answers, and perhaps for historical truth.

Q

You were born in Ipoh, Malaysia. Can you share a few favorite spots?

A

Ipoh is a so-called city in the middle of the Malay Peninsula, about one hundred miles north of Kuala Lumpur. It had a prosperous time in the nineteenth century due to its huge deposits of tin. Some Chinese miners made their fortunes and settled there, hence it formed a Chinese community. The tin market collapsed in the 1980s; Ipoh fell into decline and has not recovered to this day. In terms of development, it is one of the slower cities on the peninsula. The pace of life is so slow in fact that you can hardly think of it as a city. Young people long to leave this dull city and move to other cities in Malaysia and abroad. Therefore, Ipoh has never been crowded and is relatively quiet, which is excellent for an introvert like me.

When I was a journalist, I loved to visit the old town, which used to be the city center and then was forgotten by the young generations. I loved the atmosphere there, full of old-time charm, with rows of dilapidated buildings, old shops and restaurants operating in the traditional way, selling the most authentic local food. There I would see and meet lots of old folks who always spoke slowly, with their own distinctive tones and ways of sharing memories and stories. It had been dormant for years until the city council realized that it could be developed into a tourist site. That’s what it is now. Talk about developing a tourist site: most of the local governments in Malaysia simply have only one concept, which is to commercialize a historical site and ruin it to the extreme. Ipoh’s old town doesn’t look so old anymore. Small shops and stalls are everywhere, selling all kinds of colorful specialties that target tourists. Rents and food prices have gone up dramatically. The old folks who used to come every day to meet friends and pass their time are seen no more.

Q

What cultural offerings or trends have recently captured your attention?

A

Having been in the US for the past year, naturally I have been paying some attention to the social and cultural phenomena here. I would say the US is, like Malaysia, a multiethnic society. Therefore, I can’t help comparing it to Malaysia. Certainly, they are two very different societies, as the US is a melting pot of cultures, with its great inclusivity and freedom. We Chinese Malaysians have for generations been on high alert, not allowing ourselves to be assimilated to the dominant culture—this is very interesting, definitely worth observing and thinking about.

Li Zi Shu is the author of more than a dozen books, including the novels Worldly Land and The Age of Goodbyes, which won the China Times Open Book Award. Her work has been recognized with multiple literary prizes in Malaysia, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, including several Huazhong Literary Awards.