Introduction

The Russian Federation’s unprovoked and cruel war against Ukraine has cast a shadow over all Russian culture, it would seem. At present, one may hear voices accusing Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky of guilt for the atrocities of the Russian Federation’s army and leadership. The relation of these classics to Russian imperial violence, past and present, is an enormous topic, which we will not take up here. Instead, let us consider contemporary Russian writers and writing, which, unlike Tolstoy, have no hope of an alibi, some would argue.

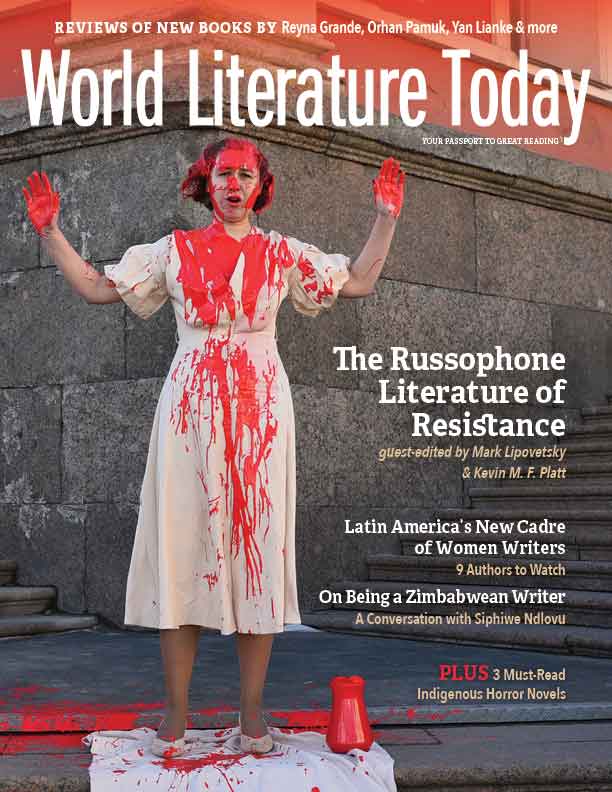

As the writing we have assembled for this special issue of World Literature Today demonstrates, the language one speaks is not a marker of complicity. In fact, what we regard as the most important writing in Russian of the past two decades has taken the form of a rejection, explicit or implicit, of Putin’s dictatorship, Russian nationalism and imperialism, homophobia, xenophobia, and the whole matrix of what official Russia now terms “patriotic” values. This writing has been global in scope, including authors from the many places in the world where Russian is spoken and from new and old emigrations. In addition to the many readers this literature has accrued over the past decades, it is fast gaining new ones, comprised of the hundreds of thousands who have fled the Russian Federation over the past year because they could not imagine continued existence in such a murderous country. We should add to these the many who, for various reasons, have remained in Russia yet regard the regime and the needless and horrific war it has unleashed with the same eyes as those who have observed it with disgust and dismay from without and those who have left. With this special issue, we hope to add the readers of WLT to this circle.

Of course, this issue can only present the tip of the proverbial iceberg. So let us sketch out in a few words the contours of the iceberg as a whole—the contours of the “russophone literature of resistance,” as we call it, drawing on important recent scholarship by Naomi Caffee, Marco Puleri, and others. In distinction from “Russian”—a contested term that may demarcate a nation, politically bounded territory, or its citizens—“russophone” refers to language alone. In the broadest sense, “russophone writing” includes far-flung and diverse communities that, perhaps, should not be regarded as a singular or unified entity at all. It embraces authors both within and without the Russian Federation. In some logical sense, russophone writing could be said to include authors of any political position at all who write in Russian—yet those aligned with the Russian Federation and its aggression would hardly agree to be described with this term. We propose that, within this large and variegated field, we may discern a globally networked community of writers working intently against the culture and politics of Putin’s Russia. Indeed, the unifying feature of russophone literature of resistance is rejection of the narratives of “great Russian culture,” “the Russian soul,” “Russia as martyr and savior,” “Russian messianism,” and the like. This is writing that explodes the cultural foundations of Russian “patriotic” ideology that, generation after generation, has fueled imperial arrogance, self-aggrandizement, ressentiment, and xenophobia.

The identity of those who resist is an uneasy one. The russophone writers presented in these pages critically, at times painfully, examine their own relationship with Russia and the Russian. Maria Stepanova, the winner of multiple literary awards in Russia and Europe, explicitly reflects on this in our interview with her: “The least apt response to this condition is to say: ‘This has nothing to do with me.’” Her poetry confronts the reader with the impossibility and absurdity of continuing to live as usual, when one’s state reveals itself as a monster: “While we slept, we bombed Kharkiv . . . While we ate, we bombed Lviv . . .” Others concur, in their own manner. Maria Malinovskaya begins her documentary poem, created from the words of an unnamed interlocutor: “I feel personal guilt in this conflict / lots of people talk about collective guilt / but I don’t think that it’s collective for me / for me it’s personal guilt.” The poem ends with a question, “can one under these circumstances / publish books / date, read poems / in Russian?” Yet this very rhetorical question is written and published as a poem in Russian. Mikhail Shishkin, a celebrated master of prose fiction, titles his latest book of essays My Russia: War or Peace?—we offer an excerpt to WLT readers. Perhaps contrary to expectations, this work is not about nostalgia or love for the homeland that Shishkin departed decades ago, but rather the story of the degradation of Russian society in the years since the anticommunist revolution of 1991. Konstantin Shavlovsky, in a poem addressed to “mama”—a metaphor for the Russian motherland—explains:

mama it’s not black and white

we’re the bad guys, we’re fools

it’s the phantoms in the kitchen

circling around your foot

Russian is spoken by millions of people of diverse ethnicities, both within the Russian Federation and outside of it. Post-Soviet russophone authors who have experienced Russian xenophobia and rising nationalism at first hand relate to Russian language and culture with a distinct intensity. To those who have told them “you don’t belong,” they respond with writing that stakes a claim to life on their own terms, to dignity, and to a language that is as much theirs as anyone else’s. Poets like Egana Dzabbarova, Ruthie Jenrbekova, and Ramil Niyazov reinvent and reinvigorate Russian with verbal infusions from Azerbaijani, Tatar, Circassian, and other languages, creating new linguistic possibilities and undermining the imperial dictatorship of normative Russian, turning poetry into a utopia of postcolonial hybridity. With their writing, alongside that of many other authors across the world, literature in Russian from outside the Russian Federation (diaspora, emigration) joins russophone literature of post-Soviet postcolonies such as Riga, Latvia, or Almaty, and literature created by ethnic minorities and aboriginal peoples within the Russian Federation in a quest for a postnational utopia.

Will this utopia prove to be more enduring than the one that has been stubbornly built over the post-Soviet decades, which worked to bring contemporary Russian writing into conversation with the experiences and discoveries of European modernists and Soviet underground authors? Alexander Skidan, one of the chief architects of that related yet distinct emancipatory literary project, offers a wartime requiem to these efforts: “too late to scroll through news and facebook / too late to write on personal and collective guilt.” A requiem, however, is not a rejection; a requiem is a form of memory—in this case of one recent tradition on which the new russophone literature of resistance is building. Together, both of these dimensions of resistance share in rejection of what postmodernist theorists termed metanarratives—grand framing stories of history and political destiny—preferring micronarratives instead: stories of concrete experience, detail instead of generalizations, close-ups instead of panoramas. They realign what Stepanova calls the “etymological armature” of words, look into the details in order to deflate and unravel stereotypes and prepackaged blocks of thought.

The russophone literature of resistance is characterized by deterritorialization and recognition of multiple, contradictory impossibilities.

The French theorists Deleuze and Guattari influentially defined a “minor literature” as “not the literature of a minor language, but the literature a minority makes in a major language.”1 This definition perfectly corresponds to the russophone literature of resistance. Like other minor literatures, this writing is characterized by deterritorialization and recognition of multiple, contradictory impossibilities—recalling Kafka’s evocation of the “impossibility of not writing, the impossibility of writing in German, the impossibility of writing otherwise” (or, in the case at hand, in Russian). As with other minor literatures, in the russophone literature of resistance nearly everything has political meaning: “every individual matter is immediately plugged into the political,” for “everything has a collective value.”

Minor though the russophone literature of resistance is, it is also large and growing. Not limited to the writers represented in these pages, it includes writers residing or located in Israel (Linor Goralik, Gali-Dana Singer), the United States (Polina Barskova, Dmitry Bykov, Alexander Stessin), Uzbekistan (Shamshad Abdullaev), Latvia (Sergej Timofejev, Dmitry Kuzmin), Germany (Vladimir Sorokin, Alexander Delfinov), Montenegro (Fyodor Svarovsky), Armenia (Lev Oborin), Georgia (Daria Serenko), the Russian Federation (Oksana Vasyakina, German Lukomnikov, Elena Kostyleva), and elsewhere. Many, many others could have been included in this list—inspiring our hope that the russophone literature of resistance, minor though it is, should all the same be recognized as a major force in the world.

New York / Philadelphia

Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, “What Is a Minor Literature?” trans. Robert Brinkley, Mississippi Review 11, no. 3 (Winter/Spring 1983): 16.