Indigenous Horror

What the world thinks it knows about Indigenous peoples of North America could be likened to a Polaroid snapshot taken off the deck of a cruise ship in a foreign land, over which European spectators will forever sigh and wax poetic, exclaiming, “This, then, is an Indian.” It is not uncommon for n8v folks dressed in regalia to be asked such guileless questions as Where is your teepee? and Do you still hunt buffalo? We live in a world that uses as the foundation for its caricature of us such Hollywood inventions as Espera Oscar de Corti, an Italian American actor who lied for many years about his heritage while working under his chosen nom de plume, “Iron Eyes Cody.” It was inevitable that in the face of such willfully comedic misunderstandings of an entire continent’s people that we would, ourselves, begin controlling the narrative through a practice that is foundational to most Indigenous cultural life—storytelling.

I have been extraordinarily fortunate to take up my bookselling vocation at a time that is remarkably rich in Indigenous voices across all storytelling genres. I have celebrated each new Indigenous children’s book, every volume of poetry—each Indigenous voice is a miracle—but it is Indigenous horror that somehow most delights me. It’s hard to imagine a genre more perfectly suited to a people whose resilience has persevered in the face of the horrifically dehumanizing force that is colonization and its concomitant atrocities—from forced removal to forced sterilization and everything in between.

Erika T. Wurth

Erika T. Wurth

White Horse

Flatiron Books

I had the opportunity to meet Erika T. Wurth at a bookselling conference and was intrigued by the premise of her new novel, White Horse, which centers Chikashsha culture and highlights the contrast of urban and reservation Natives. The Lofa (Sasquatch and Bigfoot’s gorier Chikashsha cousin) is featured as the primary villain of this story, though one could argue that the primary horror is intergenerational trauma, with the Lofa as scapegoat. This book follows Kari James, as she retraces her mother’s life in an effort to discover why she abandoned her husband and days-old infant. Wurth sprinkles in enough mysticism to mask this horror story as fantasy—until the very end, when the nature of the story is revealed in gut-punching fashion. Wurth tells this story with scenes from Kari’s favorite Indian bar, an ongoing obsession with Stephen King, and complex family relationships. It’s an utterly enjoyable read and feels both foreign and familiar to me, as an Oklahoma Chikashsha who lives in that space that exists between urban and reservation Native but occupies neither.

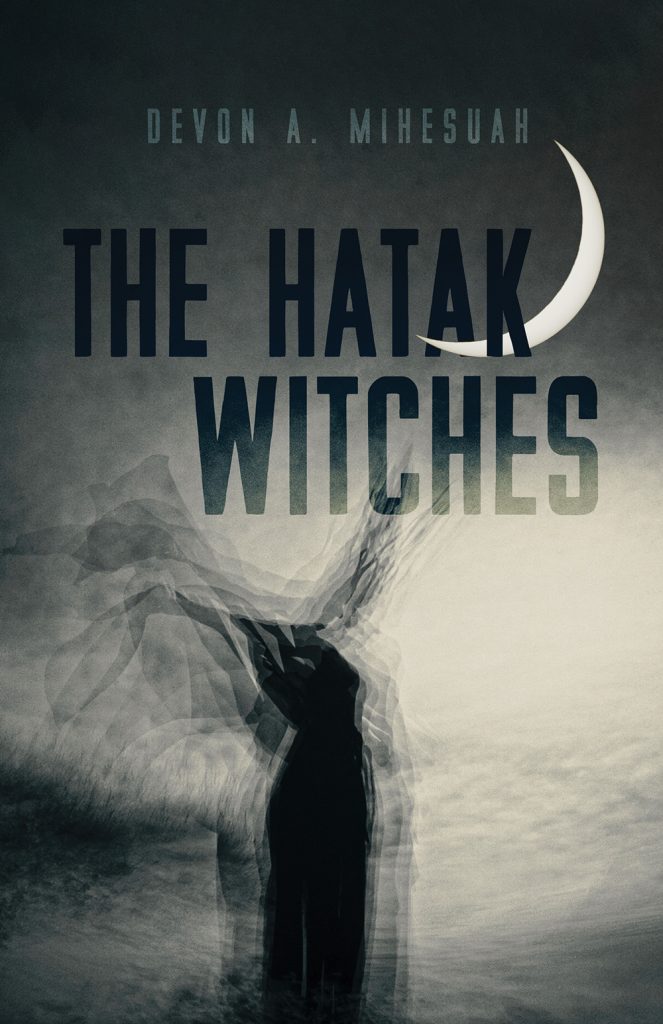

Devon A. Mihesuah

Devon A. Mihesuah

The Hatak Witches

University of Arizona Press

In The Hatak Witches, by Devon A. Mihesuah, we follow detective Monique Blue Hawk through a murder investigation in a story that blends truth and fiction with remarkable aplomb. This story, set in Oklahoma, features a place called the Hollow, whose description closely resembles my grandfather’s stories about the Cross Timbers, an ecological region of Oklahoma. His stories painted the Cross Timbers as a terrifying place, so I was delighted to find it in a horror story set in my home state. This story features shapeshifting witches, awesome Oklahoma skies, and the deep, abiding belief that owls are bringers of evil.

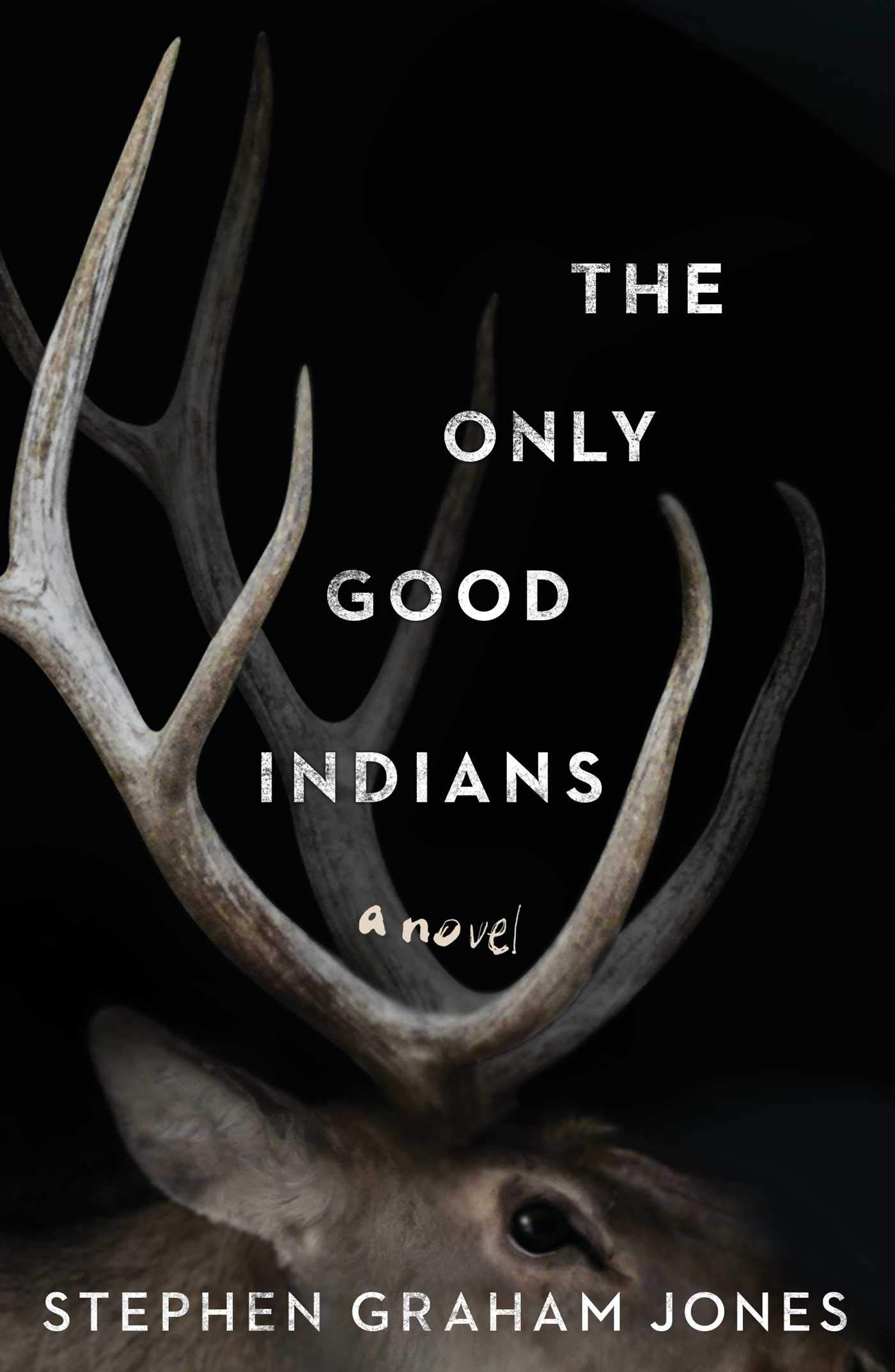

Stephen Graham Jones

Stephen Graham Jones

The Only Good Indians

Saga Press

Stephen Graham Jones’s The Only Good Indians follows a group of Blackfeet youth via a series of increasingly fantastical newspaper headlines and their matching backstories. The first half to two-thirds of this story is more a tale of woe than true horror, but in the moment the genre proves true, the reader is met with the most exquisitely casual depiction of brutality. In this way, Jones aptly elucidates the casual relationship Indigenous people have with resilience in response to violence. This story has a sharp, sometimes dry wit—slipping social commentary in with a tale of revenge that has clearly been influenced by the Deer Woman stories shared by so many North American tribes.

* * *

In reading Indigenous horror (and Indigenous stories as a whole), we are given an opportunity to throw away the sad, two-dimensional Polaroid picture and observe the tapestry that’s being created right in front of us. This tapestry is made of wry and sometimes inappropriate humor, a casual relationship with resilience in the face of violence, and a deep and abiding connection to past, present, and future. This tapestry reveals the true face of Indigeneity in all its beauty and horror; in all its stone-faced laughter; in all its wit and wisdom; in all its humanity.