Resilience and Hope after the Holocaust: A Conversation with Shoshana Bellen

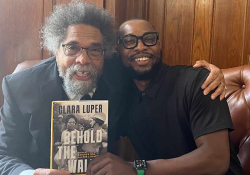

In his ongoing column, which appears in every other issue, Karlos K. Hill highlights the efforts of cultural figures doing works of essential good around issues of social justice.

Shoshana Bellen was born in Föhrenwald, Germany, in a displaced persons camp that was used to house Holocaust survivors following World War II. Now living in Israel, she returned to Germany in 2018 to attend the opening of the Badehaus Place of Remembrance (Erinnerungsort Badehaus), a historical museum and education center that occupies a renovated building which originally served as the camp’s bathhouse. Bellen was one of the contributors to the museum’s efforts to document the history of Föhrenwald through the use of photos, videos, multimedia installations, and recorded eyewitness testimony. In our recent conversation, she revealed why it was so important for her to return to the former camp after so many years and what the Badehaus project has meant to her and other Holocaust survivors and descendants in Germany and Israel.

Karlos K. Hill: Part of what I do as a historian and a journalist is bear witness to America’s decades-long history of anti-Black violence. Whether it be lynching or slavery, I bear witness to the stories of victims, survivors, and descendants. For me, it’s ultimately about justice. I’ve been involved in justice work in connection with the 1921 Race Massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and it has been some of the hardest work I’ve done in my career. Working with descendants and survivors has been particularly challenging, to the point that I’ve sometimes wanted to give up because it got too difficult. I didn’t see people ultimately doing the really hard things that are needed to build bridges. So I am encouraged to see how you, as the child of Holocaust survivors, not only were able to begin to reconcile yourself to a place and a people who had caused your family so much pain, but you were able to help others see and feel that it was something that could also be regenerative for them. Yours is a hopeful story, and it has had a profound impact on me. So I’d like to hear about how you were able to start coming to terms with the place of your birth, and with being in relationship with Germans, including individuals who might well be family members of perpetrators.

I don’t think there is justice in this world. I look more toward another word that you use, which is hope. I look more at resilience.

Shoshana Bellen: I find it interesting that justice is an important word for you. It would not be one of the first words I would use in talking about why I’m doing what I’m doing. I don’t think there is justice in this world. I look more toward another word that you use, which is hope. I look more at resilience.

One of the amazing things about the Holocaust survivors was that they did not seek revenge. There was a very small group that got weapons and wanted to hunt down the top Nazis, but for the majority of people, revenge meant having babies and continuing their lineage. If you talk to some of those who went through the Holocaust, they will point to their grandchildren and their great-grandchildren and say, “This is my revenge.”

As for this partnership involving descendants of the Nazis and descendants of the perpetrators and descendants of the victims, it’s easier to do it in Germany because the German government, German society, has taken on responsibility. They have said, “This happened”: the Nazis are part of our history, this dark period of history in our lives, and we are trying our best to recognize it, talk about it, and show it. There are other countries in the world, like Poland, that haven’t done that. So it’s harder in those countries to set up a real dialogue. But as strange as it is for me that it was German people who built this museum and are telling the story of my parents, it’s their taking on responsibility that has allowed me to reach out to them and take their hands.

Of course, the second and third generations of the perpetrators’ families are also struggling to understand and make sense of the horrors of the Holocaust. Their parents, their grandparents—everybody was part of it. I acknowledge that it has been just as difficult for them to come to terms with what happened as it has been for the Jewish second and third generations.

Hill: For me, justice can mean a lot of different things. Here in America, for instance, our legal system is based on punitive justice. But then there are other forms of justice, like transitional justice and restorative justice. I personally tend to focus on restorative justice, which revolves around what I think of as healing relationships between communities that have been in conflict. And those relationships are, as you mentioned, rooted in dialogue, rooted in conversation, rooted in working out the challenges that divided us to begin with.

In America, our conversations about justice tend to come down to reparations. But while reparations are important, it’s the quality of our relationships, and how we choose to deal with historical trauma, that we need to talk about if there is going to be real healing in the country. With respect to Föhrenwald and the Badehaus project, I see the healing as beginning with Germans’ willingness not just to accept responsibility, and to acknowledge that responsibility publicly, but to then undertake the extensive renovation of the building and all the memory work. How were you able to find the courage and strength to enter into that healing relationship and do the hard work it requires?

Bellen: There was no plan. Somehow or other, I kept crossing paths with the right people. Things were happening. The timing was right. I went to Föhrenwald, to see where I was born, at the same time that there was a reawakening in Israel among the members of the second generation, especially those who were born in the displaced persons camps. People had started looking for other people who were born in the same DP camps where they were born. And so a group was organized for the descendants of Föhrenwald. If not for that, I would never have been able to find these people. There had never been a register of any kind, but now we suddenly had one. I ended up in charge of the mailing list. It started with one name; then that person gave me another name, which led me to another name. The group has grown from maybe forty names in the beginning to a hundred names today.

And then I realized in talking with Sybille Krafft, who is director of the Badehaus, how important it was for people to send in their parents’ stories, pictures, artifacts, and whatever else they had. I would send out requests, telling them about the Badehaus, and explaining that this was a way for people to honor their parents and grandparents. There are a lot of Facebook groups for second-generation Holocaust descendants, some of which do really good work, so I posted notifications on all those pages. One person would tell me their name and where they were born, then another and another. We were able to get that initial information, but when I asked them to write a one-page family history, I lost half of them—they didn’t want to do it; it wasn’t important enough. Fortunately, though, enough of them did.

I translated everything, because some of them could write well in English, but others couldn’t. I have a computer folder where I keep all of the original documents in Hebrew and my translations. We started sending those to the Badehaus, and the more we sent, the more people contacted me. The Badehaus had already found a core of Jewish descendants who had stayed in Germany, but they’d had no way of reaching out to descendants in other places. And unless somebody googled Föhrenwald, they might not even know about the existence of the Badehaus. So I was able to provide the museum with all those testimonies.

Shai Lachmann, who is chair of the Association of the Descendants of Föhrenwald in Israel, was also born in the camp. When he decided to organize a conference, I offered to help him with anything he might want me to do, but I told him that I wanted ten minutes for myself. And he gave me those ten minutes. I knew nothing about PowerPoint, but I managed to put together a PowerPoint presentation about Föhrenwald. I had been there only two weeks earlier, so I was able to show what the Badehaus looks like today in comparison with what it looked like back then. And people got excited. For a lot of the second generation, Föhrenwald had been a nonexistent place other than when their parents would mention it, but they now had a direct link to it. We had advertised all over, including the Israeli press, so we got a lot more people at that first conference than we had anticipated. We had expected a few hundred people to attend, but we ended up with well over a thousand. A lot of them were actual survivors, and now they were meeting and talking to each other and sharing memories. It was almost like a class reunion, and the second generation stood back and watched it all.

Unfortunately, more and more of the survivors die every year. So we did the second conference very differently. We had many, many members of the second generation at that one, people who knew nothing more than that their parents had been born in Föhrenwald, that their parents were there after the war. So, we were able to give them a lot of information. I ended up going over my allotted ten minutes; I spoke for more like half an hour, and I told them about the Badehaus and what’s going on there. Shai gave them more historical information, to provide a fuller picture. And I got a few more family histories.

I haven’t done my presentation on Föhrenwald in Hebrew yet. I don’t know whether I’d actually have an audience here in Israel because so many Israelis came from other camps. The Badehaus is special to me, but in Israel, Föhrenwald is just one site among many. As far as I know, there isn’t another museum anywhere else, but some of the other places where they used to have DP camps are now starting to try to do the same kind of work that the Badehaus did. It’s said that copying somebody is a way of complimenting them, so I guess that’s a good thing. But the stars also have to be aligned—or at least that’s what I’ve found.

Right now, though, I’m speaking to the same people all the time. We aren’t finding enough new people. One person asked, “Why would I want to get involved with that? I want to move forward with my life, not backward.” For many people, the response is, “Why should I care?” A lot of people still refuse to go to Germany at all. And if they do want to go, it’s because they want to have a good time in Berlin or drink beer in Munich. So while we occasionally still get somebody new, now we just have to make sure to reach beyond the second generation, so that the third generation also knows about this.

Hill: You seem to be touching on what’s sometimes called “survivor’s guilt”: why did I survive when all those others didn’t? It feels like that weight is much heavier for Holocaust survivors. People sometimes act as if it isn’t a good thing that you can survive and tell the story.

When it comes to Holocaust survivors, it was as if they were somehow not as legitimate as those who died.

Bellen: There are many occasions on which the martyrs are honored in Israel, including the International Day of the Holocaust, but when it comes to the survivors, it was as if they were somehow not as legitimate as those who died. So we, their children, now have a way to honor them. Every year on Holocaust Memorial Day, they have a thing here called “memory in the living room,” where Holocaust survivors and members of the second generation will go to someone’s home, and the homeowners will invite their friends or other people over. It’s like an open house, and you come to hear testimony and talk.

There are actually courses offered here in Israel where you can learn how to tell a story. The idea is to keep it alive—the whole thing of “never forget.” It’s like when a pebble is tossed into water: the ripples reach out in different directions, and maybe good things will come of it. I have not yet been able to do it; there seems to be this pull toward telling the worst possible stories—you know, the horror stories of the Holocaust. The typical story is about one specific person and the trauma they went through, but I want to tell a different kind of story.

Next year, I think I’m going to do it. My daughter is a high-level manager at one of the big banks here in Israel, and she has offered to invite people from the bank to join us in her home, along with her personal friends. I will give a short account of what happened to my parents, but the story I want to tell is not about them or what happened during the Holocaust. I want to talk about what happened after. I want to include this emphasis on resilience. Maybe I will finally have the courage at seventy-seven to tell the story the way I want to tell it.

Hill: The more I hear you talk, the more I understand your story and the power of it. But I think the work you’re doing in carving out space for the second generation to honor their parents is even more powerful. It seems that most survivors of the Holocaust feel the need to hold on to the pain and trauma and not let go of it, but for you as the child of survivors, the story is one of resilience and hope.

The main thing for me is to make sure that I get the stories right, so that the new generations in Germany will see how resilient people can be no matter what you do to them.

Bellen: I personally have gotten so much out of it. When you give, you get, so maybe I gave a little bit in trying to reach out to people, but I got so much in return. That was what kept me going. Each new event had me learning new things. In addition to gaining new friends, and fascinating friends, I have also gained a new understanding of my mother and father. But the main thing for me is to make sure that I get the stories right, so that the new generations in Germany will see how resilient people can be no matter what you do to them. That, I think, is the most important lesson to be learned.

October 2022

After her birth in 1946 in Föhrenwald, Shoshana Bellen (on the right) immigrated to the US with her parents in 1949, then to Israel with her husband in 1969. Over the years she worked intensively with new immigrants, advocated for women’s rights, and marched for the promotion of a negotiated peace between Israel and its neighbors.

After her birth in 1946 in Föhrenwald, Shoshana Bellen (on the right) immigrated to the US with her parents in 1949, then to Israel with her husband in 1969. Over the years she worked intensively with new immigrants, advocated for women’s rights, and marched for the promotion of a negotiated peace between Israel and its neighbors.