Journey as Language: The Poetry of Phoebe Giannisi

Click here to read Sneeden’s translations of four of Giannisi’s poems.

Phoebe Giannisi is one of Greece’s foremost contemporary poets and is the author of six collections of poetry, including Homerica (Kedros, 2009) and, most recently, Rhapsodia (Gutenburg, 2015), and she co-edits the Greek literary journal FRMK. Her poems, along with those by her contemporaries Katerina Iliopoulou, Vassilis Amanatidis, Panagiotis Ioannidis, and others, were included in the recent landmark anthology, Austerity Measures: The New Greek Poetry.

I first met Phoebe Giannisi in New York, where she’d been a Humanities Fellow at Columbia University, and where she gave me a copy of her book Homerica—which had recently been translated into German. Reading her poems in the original, I was struck by their musicality as well as their rich synthesis of mythology and contemporary life. Compelled, I began to translate the book’s opening poems as a sort of lyrical experiment, playing and replaying the audio recording that came with the book to help me restage the poems’ internal rhyme, alliteration, and metrical variation in English. The struggle—and pleasure—was learning from the poems themselves how to convey their inventiveness of sound, their spell-cadences, which weave in Greek a verbal tapestry of rising and falling notes.

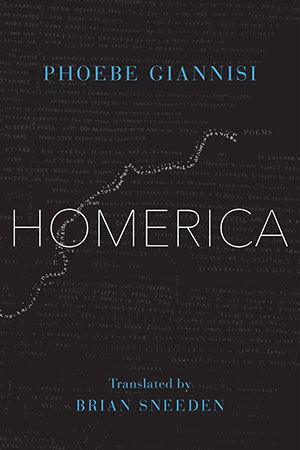

Inside Giannisi’s apartment in Athens, among her many art installations, hangs her aegis: a body-length, parchment-crackly goatskin that has been made into a lyric map. On one side is a hand-drawn map of Greece, while the other side is covered in poems, fragments of poems, and other writings, in alternating red and black inks (Giannisi’s handwriting on the aegis can be seen on the cover art of Homerica). In the center, a line of red text curves upward at an arcing angle: “this is the migration path of the Vlachs,” she tells me, referring to the nomadic people of goat herders whose seasonal route travels from the mountains of northern Greece to the sea town of Volos, where Giannisi spends most of the year teaching architecture at the University of Thessaly.

Inside Giannisi’s apartment in Athens, among her many art installations, hangs her aegis: a body-length, parchment-crackly goatskin that has been made into a lyric map. On one side is a hand-drawn map of Greece, while the other side is covered in poems, fragments of poems, and other writings, in alternating red and black inks (Giannisi’s handwriting on the aegis can be seen on the cover art of Homerica). In the center, a line of red text curves upward at an arcing angle: “this is the migration path of the Vlachs,” she tells me, referring to the nomadic people of goat herders whose seasonal route travels from the mountains of northern Greece to the sea town of Volos, where Giannisi spends most of the year teaching architecture at the University of Thessaly.

Last October, Phoebe brought the aegis to New York City for a commissioned performance at the Onassis Center’s Antigone Now! festival. Her presentation—part-poetic lecture, part-performance piece—combined poems and fragments of poems along with field recordings of the Vlachs, and footage of the goats giving birth and being sheared (για ένα χρόνο πήγαινα στη στάνη, “for a time I went among the fold”). Toward the end, Giannisi removes the aegis and the goat bell, which she wore at different times during the performance, and cuts her own hair.

Giannisi’s poems rarely travel in a straight line but rather zag and glide across multiple threads of time, like a loom interweaving strands of the mythological past.

I’d just finished translating Giannisi’s collection of poems, Homerica, and while watching her performance I was transfixed by how fluidly the “I” of her poems shifted to include others—other people but also gods, mythological heroes, and animals. As a book, Homerica is a contemporary odyssey, but not in the usual way. Its departures and arrivals fold in upon themselves, along with chronological time, so one is never entirely sure if the inhabited moment is historical, mythological, or the present (the answer seems to be somehow all three, though as the last line of her poem “Lotus-Eaters II” hints: το πάντα τώρα πάντα τώρα – “always right now always right now”). While translating, I was struck by how Giannisi’s poems didn’t contemporize the myths but internalize them into the everyday—the mortal—seamlessly, and often on the power of their music alone. The poems rarely travel in a straight line but rather zag and glide across multiple threads of time, like a loom interweaving strands of the mythological past.

These braidings of the interwoven threads of myth, animal, personhood, history, and time in Giannisi’s poems are more than free association—rather, their Delphic logic answers riddles long buried in the Greek language. As Giannisi points out, the pronoun εγώ (“I,” ego) is linguistically linked to the adverb εδώ (“here,” etho). It is this place, this moment in time, who is speaking.

University of Connecticut