Translator as Medium

The only task FitzGerald finished and published in his lifetime was his marvelous rendering of the Rubaiyat of the Persian poet Omar Khayyam, with whom he felt a curiously close affinity across a distance of eight centuries. FitzGerald described the endless hours he spent translating this poem of two hundred and twenty-four lines as a colloquy with the dead man and an attempt to bring to us tidings of him. The English verses he devised for the purpose, which radiate with a pure, seemingly unselfconscious beauty, feign an anonymity that disdains even the least claim to authorship, and draw us, word by word, to an invisible point where the medieval orient and the fading occident can come together in a way never allowed them by the calamitous course of history. “For in and out, above, about, below, / ’Tis nothing but magic Shadow-Show, / play’d in a Box Whose Candle is the Sun, / Round which the Phantom figures come and go.” The Rubaiyat was published in 1859, and it was also in that year that William Browne, who probably meant more to FitzGerald than anyone else on earth, died a painful death from serious injuries sustained in a hunting accident. – from the Rings of Saturn by W. G. Sebald, pages 200–01

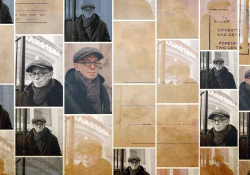

One of Merriam-Webster’s definitions of “medium” is “an individual held to be a channel of communication between the earthly world and a world of spirits.” I think this is as good a definition of literary translation as any: as a translator, I must empty myself out—“kill my own ego,” as translator and novelist Haruki Murakami says1—in order to channel the essence of the text into a plausible English incarnation. As a Buddhist, I find this a very liberating exercise; whenever I translate a text, I become free of a “self” and am able to immerse myself completely in the text, to become the narrator, in order to carry the narrator’s voice over into my own language. Translation is an intense form of listening, as well as an in-depth form of reading: I feel I have never fully “read” a text until I have translated it, until it has passed through me and become another form of itself.

In this way, translation is a lot like poetry; just as good poetry performs a kind of alchemy, transforming one thing into another (or one thing into something that is more truly that same thing, only the essence of that thing, its “true” self), translation transforms the text by making it travel from one language into another while still preserving its essence, its “true” self.

My husband, the poet Robert Kelly, says that all language is translation. Whenever we speak or write, we are translating our inner feelings and impressions into language, into words on a page or sounds in our mouth. This is a radical act, just as translation is a radical act; whenever I begin translating a book, I feel a sense of despair at the hopelessness of the task, the impossibility of taking a text that sounds perfectly fine in its own language and transforming it into my own speech, my own words. This very impossibility is the challenge and delight of translation: the translator engages in a sort of inner struggle between hopeless despair and optimistic industriousness in turning the text into Something Else but Still the Same.

In “The Search for Point Zero” in The Book to Come, Maurice Blanchot writes:

Literature begins with writing. Writing is the totality of rites, the overt or subtle ceremony by which, independently of what one wants to express and of the way in which one expresses it, this event is announced: that what is written belongs to literature, that the one who reads it is reading literature. This is not rhetoric, or rather it is a particular kind of rhetoric, destined to make us understand that we have entered this closed, separate, and sacred space that is literary space.2

Blanchot goes on to describe the writer’s quest for “the degree zero of writing”: To write without “writing,” to bring literature to that point of absence where it disappears, where we no longer have to dread its secrets, which are lies, that is “the degree zero of writing,” the neutrality that every writer seeks, deliberately or without realizing it, and which leads some of them to silence.3

Translation, too, seeks that degree zero of writing: the translator seeks to disappear into the text, to become the text, the way the medium becomes the spirit being channeled, in order to become invisible, to make the words speak for themselves. This is the sacred space of writing, and it is nothing short of magic: a transformation occurs, of both translator and text, and the two emerge from it changed, no longer the same.

[T]he translator seeks to disappear into the text, to become the text, the way the medium becomes the spirit being channeled, in order to become invisible, to make the words speak for themselves.

In this way, any time a reader picks up a book and starts to read, he or she is performing a magic rite. It could also be called a religious rite, but I prefer the word “magic.” Reading is a form of prayer, a complete devotion to and absorption in the text until the self is forgotten and one is transported into the world of the book. The same is true for translation; I regard it as a sacred act, one never to be taken lightly, a complete commitment to the text without regard for self or ego. In order to enter that sacred space of literature, one must go through a kind of transformation oneself; one must trust completely in the words on the page and in their ability to evoke a landscape, a world, in the translator’s mind. The translator becomes alchemist, absorbs the words in the “original” language and transforms them into his or her own “original” language, in the hope (prayer) that they will resonate with other readers in the same way they resonate with the translator.

Murakami, in discussing his two activities of writing novels and translating, says, “The process of switching between the two opposite types of works seems to help improve what could be considered the flow of psychic energy.”4 Since translation involves an emptying-out of the ego, I would imagine it would be a relief to a novelist, a kind of cleansing ritual, to forget about himself for a while and engage fully in a text that is not “his.” To become a medium. Which is also defined as a “material or technical means of artistic expression (such as paint and canvas, sculptural stone, or literary or musical form)” and “a condition or environment in which something may function or flourish.”

Since I make it a policy never to read ahead in the text I’m translating, I feel more the way a spiritual medium might feel, since the text is “speaking” to me as I write; it’s almost as if the text were flowing through me, in an immediate and breathless way. The text feels more alive to me when I haven’t read it ahead of time, more like a living presence and less like lifeless words on a page.

Recently I read an article in which the author and translator were compared to a composer and musician. I don’t think this is a very good metaphor for the act of translation. As a musician, I can interpret a musical piece differently from another musician, but that piece will still be basically the same; it won’t have been transformed into something different but the same. It will also still be immediately recognizable as a piece by, say, Mozart or Beethoven. If three different translators translate the same text, however, the reader might have a completely different impression from text to text; the personality of the narrator will be changed by the personalities of the different translators. This is because each translator has a completely different world-view and way of expressing it. If three different people see the same landscape, each person will describe it in a different way, according to that person’s reference points and memories and background, just as van Gogh and Picasso would paint the same landscape in entirely different (and possibly unrecognizable) ways. I think a more apt metaphor for translation would be that of landscape and painter, in which the author is the landscape seen, and the translator is the painter, writing down what she/he sees and feels. In that way, no translation is “wrong” or “right,” just as no painting is wrong or right; each one is an interpretation of what the translator sees. A “good” translation is one in which the translator has managed to reach that degree zero of writing, that sacred space where writing, and self, disappear.

I think a more apt metaphor for translation would be that of landscape and painter, in which the author is the landscape seen, and the translator is the painter, writing down what she/he sees and feels.

In the quotation cited at the beginning of this essay, Sebald describes Edward FitzGerald as having a “curiously close affinity” with Omar Khayyam “across a distance of eight centuries,” and goes on to say: “FitzGerald described the endless hours he spent translating this poem of two hundred and twenty-four lines as a colloquy with the dead man and an attempt to bring to us tidings of him.” Any time a translator translates a text, he or she enters into a kind of communion with that text until it becomes a colloquy with the author (dead or alive). Every translation is an attempt to bring the reader tidings of the “original” text in the hope that translation itself will disappear and will seem as “original” as the original. In this way translation is an attempt to commune with the beyond, with the untranslatable, and to make what is ethereal and ungraspable into something concrete and readable. It is a sacred act of communion for the translator, and hopefully for the reader as well.

Editorial note: This essay was originally published in Turkish in the July issue of the literary journal Sabah Ülkesi.

Footnotes

[1] Haruki Murakami, in an article in The Asahi Shimbun.

[2] Maurice Blanchot, “The Search for Point Zero” in The Book to Come, trans. Charlotte Mandell (Stanford University Press 2002) pp. 205–06.

[3] Idem, p. 207.

[4] Quoted in The Asahi Shimbum.