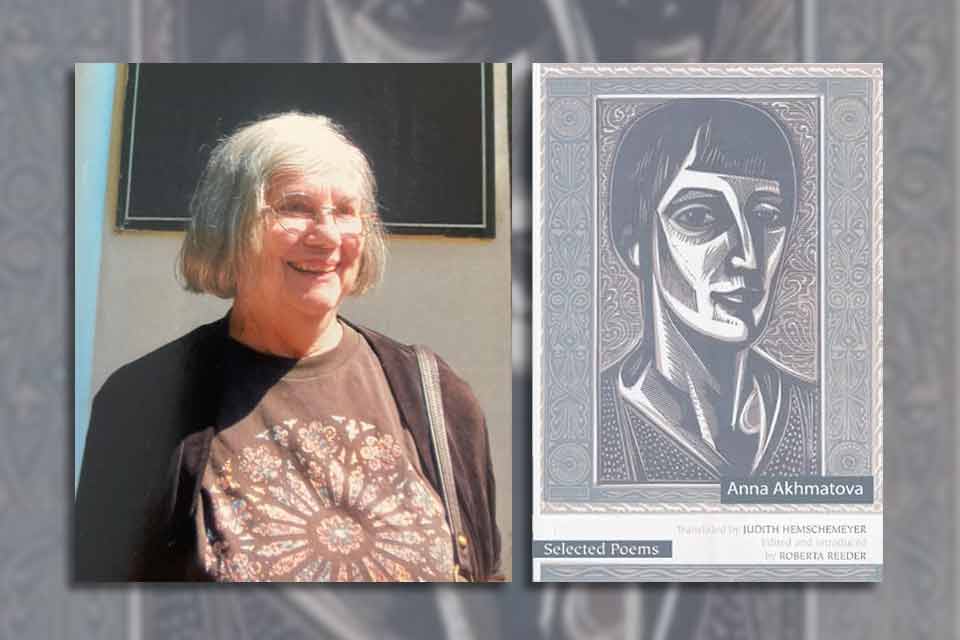

Pilgrimage and Passion Project: Remembering Judith Hemschemeyer

Three days shy of her ninetieth birthday, poet, teacher, and translator Judith Hemschemeyer (1935–2025) passed away quietly in Roanoke, Virginia, far in time and space from the Soviet Union and the dictatorship of Joseph Stalin that ruthlessly persecuted Anna Akhmatova (1889–1966), the courageous and charismatic poet Judith studied and translated as only a sister poet could. Judith, whose own poetry reflects a rich interior life, never lost the boldness and passion that drew her to the rebellious Akhmatova and led her, intrepid in her late seventies, to make her first journey to Russia to visit the Anna Akhmatova Museum in the Fountain House in St. Petersburg. It was there that Akhmatova lived for almost thirty years, near the prison where her first husband and son were held. It was there that she and friends committed to memory drafts of her poems, including “Requiem,” arguably her most famous and powerful work, before burning them to escape the notice of the Bolshevik secret police.

First, a caveat and context. I am not a poet, not a scholar of Russian literature, and not a close friend of Judith, but I had the good fortune to be a fellow traveler on a Baltic cruise with her in June 2014. My friend Kathleen Bell, also friend and colleague at the University of Central Florida to Judith, spotted an itinerary that included a stop in St. Petersburg. Since, however, the museum was not considered a state-sponsored tourist attraction, Kathleen found a private tour to accommodate our group of nine and secured official permission with a sanctioned guide, a university linguistics professor. Judith was an unlikely cruiser in so many ways—a huge ship replete with casinos, designer shops, and Broadway shows was hardly her style—but she kept her eye on the prize, the reason she embarked on the cruise. Also, during our travels, Kathleen and the Australian composer Moya Henderson, Judith’s dear friend and partner, arranged opportunities for Judith to acquaint us not only with Akhmatova but her own journey to become one of her foremost translators.

I had read some of Judith’s poetry and knew a little of Akhmatova, but during that cruise I learned that Judith basically taught herself Russian starting in 1973 after she became enchanted with Akhmatova and was determined to read the poetry in its original language. Her translations from Russian to English, a scholarly project that took more than a decade and included support from a Hodder Fellowship from Princeton University, resulted in The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova,edited by Roberta Reeder (Zephyr Press, 1990), widely acclaimed as a groundbreaking contribution to literary history (see WLT, Spring 1991, 318).[i] During our “cocktail seminars,” as I recall our gatherings aboard the ship, Judith talked of the poet as if they were beloved friends, and indeed she brought Akhmatova into her own work. In her final published book of poetry, Lovely How Lives, Judith wrote:

Lovely how lives of the great overlap

or just miss. Between Dickinson’s death

and Akhmatova’s birth — a three-year gap.

Dickinson’s ukase: “Tell all the truth

but tell in slant” was in capable hands.

Amherst was always Amherst,

but Akhmatova lived, and her work was banned,

in protean St. Petersburg,

renamed Petrograd, then Leningrad ,

as war and revolution swamped the land,

but not the soul of this “seaside girl.”[ii]

When at last Judith made her way to the Anna Akhmatova Museum, she was almost giddy—a pilgrim on sacred ground. Opened in 1989 on the centennial of the poet’s birth, the apartment includes artifacts, photographs, original manuscripts, and a tranquil sculpture garden. Judith walked and touched and listened with the rapt attention of an explorer more than an expert academician. But what absolutely thrilled her were the young staff of students and scholars there to honor and continue the legacy of Akhmatova. Judith welcomed—perhaps “treasured” is not too strong a word—their dedication to pass on to future generations not only the poetry but the indomitable spirit of this woman who was so much a part of Judith’s own life.

When at last Judith made her way to the Akhmatova Museum, she was almost giddy—a pilgrim on sacred ground.

After that cruise, I wanted to read more, learn more about both of these poets. I was not surprised to find in Judith’s translator’s preface to the Collected Poems her confident commitment: “I became convinced that Akhmatova’s poems should be translated in their entirety, and by a woman poet, and that I was that person.” I am grateful she held steady to that belief and hope she will inspire others, as she inspired me, not only to appreciate Akhmatova but by her own example to hold fast to the passion that animates true scholarship and creativity, passion that refuses to be dampened by age or circumstances. I hold dear the poem that Judith sent to me early in 2015 with the comment that this poem was “the first one I’ve written in a long time.”

A Visit to the Akhmatova Museum

Russia — so vast, so strangle-hold small.

Here is the dead-end hallway where her son

Had to sleep whenever he was released,

his suitcase, his books on a narrow shelf

over his head. And here is the ashtray

where she and Chukovskaya cremated

“Requiem,” each banned poem burned as soon

as they committed it to memory,

strewed its ashes over the soul, the soil

of their Russia — so vast, so strangle-hold small.[iii]

What a gift to remember our experience in St. Petersburg, a moment in time, through Judith Hemschemeyer’s eyes—and words.

Columbus, Ohio

[i] A review of The Complete Poems (1990) appeared in the New York Times. Zephyr Press issued an updated and expanded edition of The Complete Poems in 1997.

[ii] The full poem “Or Just Miss” appears in Lovely How Lives (Snake Nation Press, 2010). This was Judith’s fifth poetry collection.

Editorial note: Leonid D. Rzhevsky’s review of Akhmatova's Rekviem appeared in the Summer 1964 issue of WLT.