The Intellectual Venture of Theodore Ziolkowski

To view the photo captions, toggle the circled “i” in the upper lefthand corner of the image frame.

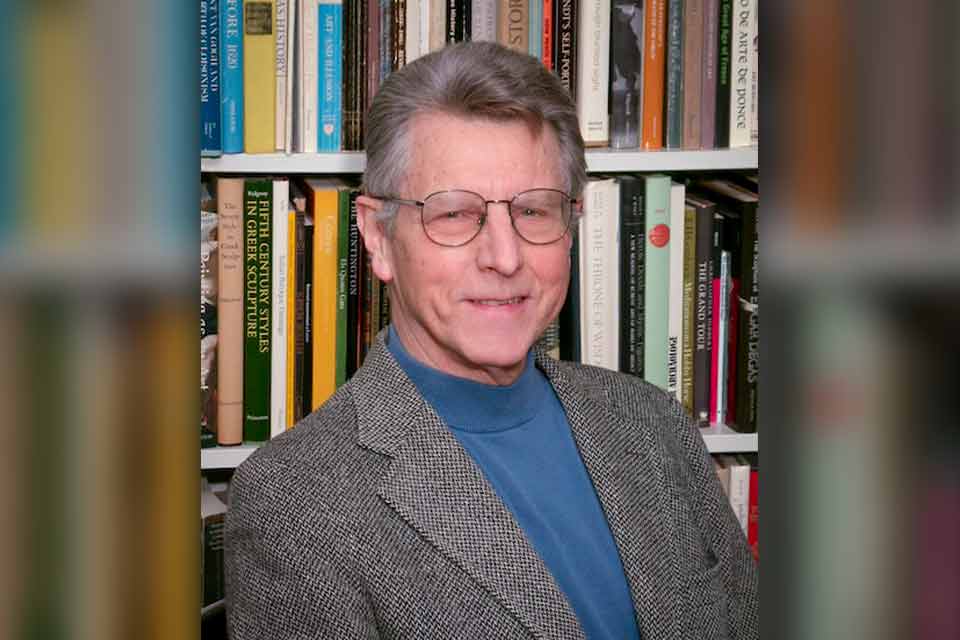

The following is excerpted, with several very slight modifications, from my foreword to the Polish translation of Theodore Ziolkowski’s 1972 monograph Fictional Transfigurations of Jesus, which is forthcoming in Polish as Powieściowe transfiguracje Jezusa from Wydawnictwo Test (Lublin) in 2026. As one of World Literature Today’s longest-serving editorial board members and contributors, from 1957 to his passing five years ago today, my late father played an important role in the second half-century of the journal’s development. As WLT approaches its centennial year, I hope the journal’s readers will appreciate the following intellectual biography, which situates my father’s personal life and scholarship during that time frame. (I am grateful to my siblings, Margaret Ziolkowski and Jan Ziolkowski, for kindly confirming some recollected facts for me.)

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Theodore Ziolkowski (1932–2020)—“Ted” or “Teddy” to family and friends—grew up entirely in the nearby college town of Montevallo, until he departed for college at age sixteen. (Information about my father’s Polish ancestry can be found in the boxed note at the end of this piece.) In some respects, although he was the son of a first-generation Polish American mother (Cecilia Ziółkowski, née Jankowski) and a Polish émigré father (Mieczysław Ziółkowski), his boyhood was quintessentially American. An accomplished boy scout and gifted athlete, he played on the high school (American) football team, which he captained his senior year.

He also manifestly inherited the musical genes of his parents, both of whom were professional musicians. Said to have been left often as an infant to sleep in a basket beneath the piano his father was practicing on, he was taught the rudiments of piano and music as a child by his mother but, out of a later-acknowledged resistance to parental authority, took up another instrument, an antique cornet (inherited from an uncle, a band leader in Illinois whom he had never known), and learned on his own how to play it after his parents arranged for him to be taught mouthing and fingering by a local college student who played French horn. Abandoning the piano entirely by age ten and turning mostly away from the tradition of Western classical music represented by his parents, young Theodore—drawn by the sounds of Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke, among others—immersed himself passionately in American jazz and swing band music as a precocious cornetist and, later, a trumpeter known for his improvisational skills, playing in a high school dance band. During his high-school junior year, when Ziolkowski was on the football team, his band teacher arranged for him to play in the marching band at halftimes in his full gridiron garb! The next year, as team captain, he escaped “that particular indignity,” as he would later call it; but players on the opposing teams still called him “Music Man.” That same year he joined with two college students to perform regionally as a combo they called the Starlight Trio.

Young Theodore—drawn by the sounds of Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke, among others—immersed himself passionately in American jazz and swing band music as a precocious cornetist.

But what about the development of Theodore Ziolkowski into a scholar of literature? How did that come about?

I remember once reading the suggestion by someone—I believe it was Czesław Miłosz—that the relationship of the Polish language to Latin is comparable to that of a lush vine that has wound itself around the trunk of an ancient, sturdy tree. Something loosely analogous could be said about the role that Latin played in Theodore Ziolkowski’s intellectual life: although he would be known professionally as a Germanist, the first language he learned beyond his native English in boyhood was Latin, for which he maintained a lifelong love, and which later furnished the basis of a significant portion of the scholarly oeuvre he produced as an adult scholar. Ziolkowski as an adolescent was privately tutored in Latin by his father’s colleague and friend, Dr. Edgar Reinke, a professor of German and Latin at the college where Mieczysław taught music and piano performance. In the initial year, his junior year in high school, Theodore went to Dr. Reinke’s apartment each afternoon after football practice and learned the fundamentals; over the summer, he was expected to read and translate portions of Caesar; and in the second autumn, after football practice, he and Dr. Reinke read Cicero and, in the spring, Virgil. Theodore’s start with German was similar. During the summer before he entered college, his father taught him the rudiments of German (the secondary native language, together with Polish, of Mieczysław, who had grown up in Poland’s Prussian Partition).

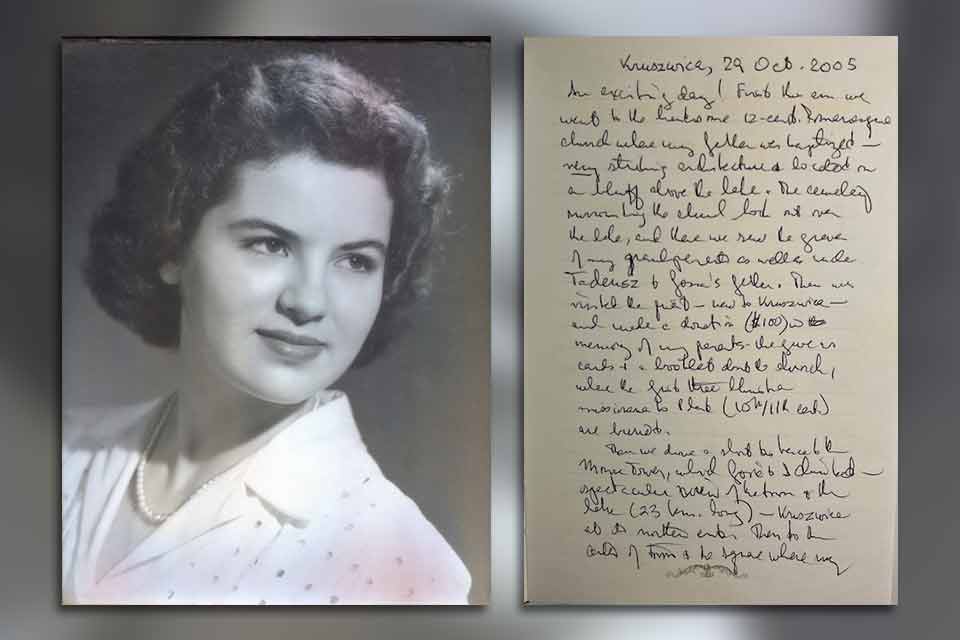

Theodore Ziolkowski attended Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, where he earned his AB degree magna cum laude in 1951 at age eighteen, majoring in German, and then his MA the following year, with a concentration in German and Greek. (By no mere coincidence, his younger brother John E. Ziolkowski grew up to be a professional classicist who taught courses in Greek and Latin in the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at George Washington University in Washington, DC, where he is now a professor emeritus.) During his Duke years, Ziolkowski continued to distinguish himself as a jazz trumpeter, playing first in the concert band and, later, in the top-notch Duke Ambassadors band. It was also while he was at Duke that, in 1951, he married Yetta Goldstein, a fellow Alabamian he had met while she was a student at Montevallo, and whose father (Samuel Jacob Goldstein, né Olewnik), like his, had immigrated from Poland—from Ciechanów, in the Russian Partition, in 1903. Theodore and Yetta would remain married for almost seventy years, until his death in 2020; she passed away just over two years later.

Funded by a Fulbright Fellowship, Ziolkowski studied German language and literature in 1952–53 at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, before entering Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, on a Yale University Fellowship. Studying under the direction of the eminent US-born Germanist Herman J. Weigand, he held a Yale Junior Sterling Fellowship in 1954–55 and received his PhD in German from Yale in 1957. His doctoral dissertation analyzed parallels in the works of Herman Hesse, the German-born Swiss awardee of the 1946 Nobel Prize in Literature, and the German Romantic poet and writer Novalis. While working toward his doctoral degree, Ziolkowski taught as an instructor on the Yale faculty in 1956, and, after receiving his doctorate, he pursued studies in 1958–59 as a Fulbright Research Fellow. From 1960 to 1962 he taught as an assistant professor at Yale before being hired that fall as an associate professor in the Graduate Faculty at Columbia University in New York City, where he taught until he was called in 1964 to the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures at Princeton University, which hired him at the rank of professor—a hiring that made him, at age thirty-two, one of the youngest full professors in any field in the United States at that time.

When the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures at Princeton University hired Ziolkowski in 1964 at the rank of professor, that made him, at age thirty-two, one of the youngest full professors in any field in the United States at that time.

It is worth noting that, following his return from his Fulbright year in Innsbruck, throughout his years as a graduate student and then assistant professor at Yale, Ziolkowski performed regularly as a trumpeter in various unionized, professional jazz bands to complement his and his wife’s otherwise modest academic earnings—hers as a high school Latin teacher—and to support their growing family. (My sister, Margaret Cecilia Ziolkowski, was born in 1952; my brother, Jan Michael Ziolkowski, in 1956; and I, my parents’ third and last child, in 1958.) His principal musical employer during this time was the well-known entrepreneur Eddie Wittstein, who engaged a large group of musicians to perform at all sorts of events, from small weddings and bar mitzvahs to large balls, throughout New England and as far south as South Carolina. Only in 1962, upon moving from New Haven to New York State for the position at Columbia, did Ziolkowski make the difficult decision to relegate his trumpet to the closet, let his musicians-union membership lapse, and devote himself full-time to his scholarship and teaching.

At Princeton, where Theodore Ziolkowski would spend the rest of his career, he was appointed in 1969 to the Class of 1900 Professorship of Modern Languages; served as chair of his department from 1973 to 1979, when he was named dean of the Graduate School, a position in which he served for thirteen years (1979–92), longer than any other dean except the first, Andrew Fleming West (1901–28). Ziolkowski also held a joint appointment in the Department of Comparative Literature from 1975 to his retirement from Princeton in 2001. During his thirty-seven years at Princeton, he taught undergraduate courses on “European Short Fiction from Boccaccio to the Present”; “Prefigurative Themes in World Literature”; “Literature and Law”; and an “Introduction to German Literature.” He additionally taught graduate seminars on German Romanticism, “The Modern German Novel,” “The Faust Theme in European Literature,” and German poetry.

At different times, he was a visiting professor at Rutgers University, Yale University, the City University of New York, and the University of Munich as well as Benjamin Meaker Professor at the University of Bristol (England), visiting lecturer at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, and lecturer for the Ministry of Education in Korea. He also lectured widely at universities and conferences throughout the US and Canada, all over Europe, and East Asia. Additionally, he and his wife hosted numerous distinguished German writers for sojourns of varying lengths in their Princeton home: of these, Heinrich Böll and Max Frisch were the two with whom my parents had the closest friendships (from the 1950s on); others included Paul Schallück, Peter Handke, Hubert Fichte, and Friedrich Christian Delius. (His correspondence with these and numerous other writers, including Hermann Hesse, can be found in the Theodore Ziolkowski Collection on Literature at Princeton University’s Firestone Library.)

As a scholar, Ziolkowski was an authority on German and European literature from the age of Romanticism to the present, with a special focus upon the history of literary themes (a field of study he called “thematics”), the modern literary reception of classical Greco-Roman antiquity, and the interconnections of literature with religion and law. Aside from the books he translated from the German, Dutch, and French with his wife, Yetta, including Herman Meyer’s The Poetics of Quotation in the European Novel (Princeton, 1968) and Hermann Hesse: A Pictorial Biography (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1975), and aside from the well over two hundred articles that he published on a wide array of literary, cultural, and educational topics, and over four hundred reviews for German, English, and American journals, Ziolkowski wrote and published thirty-five monographs—twenty of them in the last nineteen years of his life, following his retirement from Princeton. To Yetta, the most thorough and exacting reviewer of his manuscripts, he often commented that he would not know what to do with his time if he weren’t writing.

Ziolkowski wrote and published thirty-five monographs—twenty of them in the last nineteen years of his life, following his retirement from Princeton.

Ziolkowski devoted three of his earliest books to Hesse: The Novels of Hermann Hesse (Princeton, 1965; see BA, Winter 1966, 69), which derived largely from research supported by his 1958–59 Fulbright and an additional grant from the American Philosophical Society; Hermann Hesse (Columbia, 1966); and Der Schriftsteller Hermann Hesse (Suhrkamp, 1979; The Writer Hermann Hesse). He further edited six volumes of the American edition of Hesse’s works (Farrar, Straus & Giroux) and a collection of critical essays on Hesse (Prentice-Hall, 1973). Although he was gratified that Hesse, who died in 1962, became one of the most popular writers on university campuses in the United States later in that decade, Ziolkowski regarded this Hesse craze—which led to Hesse’s becoming the reputedly “most-translated” German writer of the century—with a healthy amount of skepticism. It is fair to say that he was wary that the pop-status Hesse had achieved as a countercultural icon among American youth would eclipse serious appreciation of the literary and aesthetic value of Hesse’s works.

Beyond his works on Hesse, the other two books Ziolkowski produced in the 1960s remained squarely situated in Germanistik, the study of German literature: his Hermann Broch (Columbia, 1964), the first monograph in English devoted to that important German novelist, and his Dimensions of the Modern Novel (Princeton, 1969). This latter book, parts of which were written with the financial aid of a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation grant (1965), examines five German novels—Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, Kafka’s The Trial, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, and Broch’s The Sleepwalkers—as representative of five major themes or “dimensions” in modern European literature: time, death, criminality, madness, and the crisis of the thirty-year-old. In his treatment of these five novels, Ziolkowski exhibits certain methodological tendencies that will remain consistent hallmarks of his future scholarship: a thematic focus and an approach that is dually textual and contextual, structural-analytical and analogical-comparative. This contrapuntal concern with text and context was accompanied by what Ziolkowski once described (in the preface to his 1965 Hesse book) as his “critical perspectivism”: because his approach to individual literary works, and to literature generally, was determined first and foremost by problems of intrinsic theme and structure, he never regarded his own interpretations as “exclusive or restrictive” (though he acknowledged his hope that they were “valid”!). At the same time, he remained always wary, within literary studies, of the importation or imposition of “theories” or ideologies extrinsic to the examined texts. In this regard, during the 1980s and 1990s, when deconstruction and other postmodern fashions reigned supreme in literature departments at American universities, he sometimes found occasion to quote the characteristically pointed comment his doctoral mentor, Dr. Weigand, once made to a Yale colleague renowned as a pioneering literary theorist: “You don’t really like literature, do you?”

The eighth chapter of Dimensions of the Modern Novel, focusing on the theme of the thirty-year-old hero, shows hints of the special concern that came to full fruition several years later in Ziolkowski’s Fictional Transfigurations of Jesus (Princeton, 1972). The thirtieth year of a person’s life, observes Ziolkowski, marked for medieval Christians the start of the aetas canonica, because Jesus at that age went into the wilderness and then embarked on his ministry. Thus, Ziolkowski will point out in that latter study, in the cases of many of Jesus’s “fictional transfigurations,” the hero’s age is typically associated with Jesus: the corporal in William Faulkner’s A Fable (1954) is thirty-three when executed; the eponymous protagonist of John Barth’s Giles Goat-Boy (1966) is at that same age when he disappears for good; as is the hero of Harold Kampf’s When He Shall Appear (1953) when he is put on trial. Fictional Transfigurations of Jesus, which received the James Russell Lowell Prize and was nominated for the National Book Award, analyzes a full score of European and American novels featuring a plot that is, as Ziolkowski put it, “prefigured” by the gospel narratives.

The next four books Ziolkowski published reflect his routine rotation as a scholarly writer between cross-cultural thematic studies that are categorizable under the rubric of comparative literature and studies that fall more squarely within the more specific area of Germanistik. Disenchanted Images (Princeton, 1977), a compilation of his articles on offbeat, comparativist, thematic subjects, traces the motifs of walking statues, haunted portraits, and magic mirrors through European and American fiction of the nineteenth and twentieth century. Next, The Classical German Elegy (Princeton, 1980) returns to the realm of Germanistik, defining and surveying the development of a previously unrecognized but major genre in German poetry from 1795 to 1950. Varieties of Literary Thematics (Princeton, 1983) swings back into the comparativist sphere, this time exploring literary images of an even more unusual nature than in Disenchanted Images, such as symbolic teeth, mystic carbuncles, and talking dogs, all of which he presents as the basis for a methodology of literary thematic studies. Then, returning once again to Germanistik, only this time examining his subject within a broader historical-cultural context, German Romanticism and Its Institutions (Princeton, 1990) challenges the clichéd image of the Romantics as withdrawn, inward, aesthetic escapists by taking an “institutional approach” (Ziolkowski’s term) to the Romantic movement, mindful of Goethe’s conviction that we penetrate most swiftly to the comprehension of a historical era through its institutions. As much as, if not more than, any other work by Ziolkowski, German Romanticism and Its Institutions reflected the situation of his professional life at the time he wrote it. By then, he had been dean of Princeton University’s Graduate School for a full decade. Serving his own institution in this capacity led Ziolkowski to reflect extensively and deeply upon the role, significance, and potential of the university as an institution in society. Accordingly, his book examines German literature of the Napoleonic period in the context of five exemplary institutions: mines, the law, the madhouse, universities, and museums.

Ziolkowski [routinely rotated] between cross-cultural thematic studies that are categorizable under the rubric of comparative literature and studies that fall more squarely within the more specific area of Germanistik.

During his thirteen years as dean of the Graduate School, Ziolkowski achieved national recognition not only as president of the Modern Language Association in 1985 but also as an staunch advocate and defender of the humanities in US higher education—for example, participating in 1981 as a delegate on President Ronald Reagan’s Task Force on the Arts and Humanities, and testifying in 1990 before a US Senate subcommittee in Washington on behalf of the reauthorization of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Yet, throughout those years of administrating, he continued perennially offering his undergraduate course on the development of the European novel, and he never ceased researching, writing, and producing as a scholar. On the contrary, he always considered himself first and foremost a scholar and teacher, one who was temporarily serving his institution as a dean—never exclusively an administrator, and always the antithesis of a bureaucrat. Looking back at the impressive list of substantive articles that he published during his ten-plus “deaconal” years (as he called the decade of the 1980s encompassed by his deanship, playing on the Latin etymology of “dean,” decanus, from decem, “ten”), Ziolkowski attested to being gratified by the thematic coherence that linked many of those articles. Articles such as “The Romantic Origins of the Modern University,” “Doorways to Literacy,” “The Responsibility of Knowledge,” “Faust and the University,” “The Ph.D. Squid,” among numerous others that he wrote and published while dean, represented what he termed the “deanly” aspect of the same topics that occupied him as a scholar and teacher.

Virgil and the Moderns (Princeton, 1993), published by Ziolkowski during the last year of his deanship, surveys the reception of that Roman poet and his works by twentieth-century European and US writers. While harking back to his boyhood love of Latin, this work also inaugurated a book-studded sequence of Ziolkowski’s subsequent scholarship on the reception of Greek and Roman classics in literature from the early modern period up through modernity: Ovid and the Moderns (Cornell, 2005), which received the Robert Motherwell Book Award of the Dedalus foundation; Mythologisierte Gegenwart: Deutsches Erleben seit 1933 in antikem Gewand (Fink 2008; Mythologized Present: German Experience Since 1933 in Ancient Garb); Die Welt im Gedicht: Rilkes Sonette an Orpheus II.4 (“O dieses ist das Tier, das es nicht giebt”) (Königshausen & Neumann, 2010; The World in Poem: Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus II.4 [‘O this is the beast, that never existed’]); Minos and the Moderns: Cretan Myth in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art (Oxford, 2008); and his final book, which appeared the year he died, Poets in Modern Guise: The Reception of Roman Poetry Since World War I (Camden House, 2020).

This Greco-Roman branch is but one within a wide assortment of distinct branches that continued to flourish simultaneously over the last several decades of his life on the magnificent tree that is the scholarly corpus of Theodore Ziolkowski. Another major branch—or perhaps a twin trunk, together with the Greco-Roman trunk—of Ziolkowski’s scholarly tree is the German Romantic trunk. Stemming from his doctoral dissertation that related Hesse to Novalis, and developing through German Romanticism and Its Institutions, this branch or trunk continues with Das Wunderjahr in Jena (Klett-Cotta, 1998; The Miracle Year in Jena), the first book in his tetralogy of “chronotopological studies” of German Romanticism, chronicling the remarkable literary and intellectual ferment that occurred in the year 1794–95 in the university town of Jena. Das Wunderjahr in Jena was followed by Berlin: Aufstieg einer Kulturmetropole um 1810 (Klett-Cotta, 2002; Berlin: Rise of a Cultural Metropolis around 1810); Vorboten der Moderne: Eine Kulturgeschichte der Frühromantik (Klett-Cotta, 1996; Harbingers of Modernity: A Cultural History of Early Romanticism); Heidelberger Romantik: Mythos und Symbol (Winter, 2009; Heidelberg Romanticism: Myth and Symbol); and Dresdner Romantik: Politik und Harmonie (Winter, 2010; Dresden Romanticism: Politics and Harmony).

The Greco-Roman branch is but one within a wide assortment of distinct branches that continued to flourish simultaneously over the last several decades of Ziolkowski’s life on the magnificent tree of his scholarly corpus.

Two other books on this major Romantic branch of Ziolkowski’s works are Clio the Romantic Muse: Historicizing the Faculties in Germany (Cornell, 2004), which received the Barricelli Prize of the International Conference on Romanticism, and Stages of European Romanticism: Cultural Synchronicity in the Arts, 1798–1848 (Camden House, 2018). Clio the Romantic Muse, taking once again the “institutional approach” introduced in German Romanticism and Its Institutions, looks at the newly established University of Berlin in 1810, while Stages of European Romanticism presents a “unified view” of European Romanticism by analyzing representative works from music, literature, and visual art in “stages” as they occurred at ten-year intervals from 1798 to 1848: for example, Beethoven’s Pathétique sonata (1798), Mickiewicz’s poem Konrad Wallenrod (1828), and Delacroix’s painting Médée furieuse (1838). This method enables Ziolkowski to demonstrate the hallmarks of the Romantic movement in its intellectual-historical context. He is thus able to recognize the commonalities connecting the works synchronically (within the same stage) as well as the differences distinguishing them chronologically (between the different stages), such as “the waxing and waning of religious themes, the shifting visions of landscapes, the gradual ironic detachment from early Romanticism” as the movement “expands beyond England and Germany to France, Italy, Poland, and other countries—including ultimately the United States.”

Stemming from Varieties of Literary Thematics, another major branch of the Ziolkowski scholarly tree, his studies of specific literary “myths” or themes, features such books as The View from the Tower (Princeton, 1998), which examines the lives and works of four poets and writers—W. B. Yeats, Robinson Jeffers, R. M. Rilke, and C. G. Jung—who dwelled in towers immediately after World War I to escape from modern technological society and thematized those towers in their writings; The Sin of Knowledge (Princeton, 2000), which surveys the myths of Adam, Prometheus, and Faust from their origins up through their incorporation in twentieth-century literature; and Hesitant Heroes: Private Inhibition, Cultural Crisis (Cornell, 2004), which identifies determinative junctures in the careers of Aeneas, Parzival, Hamlet, Wallenstein, and other literary heroes. Another flowering from this thematic branch of Ziolkowski’s monographs is The Mirror of Justice (Princeton, 1997), which received Phi Beta Kappa’s Christian Gauss Award for outstanding book in the field of literary scholarship or criticism. Approaching its subject in a manner that combines literary history with thematics, the book surveys the history of Western law as its foremost crises have found expression in literary masterpieces from Greek antiquity up through the twentieth century.

Yet another, relatively late shoot from the Ziolkowski tree of scholarship is the vine that considers works of music alongside works in other art forms. This scholarly vine, winding itself around among the other branches (somewhat like Polish around Latin!), and reflecting his upbringing as a son of two professional pianists and his own former career as a professional cornetist and trumpeter, begins with Scandal on Stage: European Theater as Moral Trial (Cambridge, 2009). This book examines the notorious controversies triggered by the debut performances of ten operas and plays in Germany and France, from Schiller to Bertolt Brecht, Richard Strauss, and Kurt Weil. Subsequent books in which musical compositions continue to come under Ziolkowski’s scholarly scrutiny together with literary texts and, now, works of visual art as well, include Classicism of the Twenties: Art, Music, and Literature (Chicago, 2015), Music into Fiction: Composers Writing, Compositions Imitated (Camden House, 2017), and the above-mentioned Cultural Synchronicity in the Arts, 1798–1848. Notably, from his mid-seventies on, that is, during the years he wrote these books, Ziolkowski on his own took back up playing the piano, the instrument he had given up for the cornet as a boy. Only now, his attraction was specifically to Bach, not jazz. Practicing routinely for two hours at the end of each day, despite the multiple surgeries he underwent to counter the Dupuytren’s contracture that afflicted and disfigured practically all the fingers of both his hands late in life, Ziolkowski stoically worked his way, slowly and methodically, through the entirety of The Well-Tempered Clavier, memorizing each piece before proceeding to the next.

Ziolkowski stoically worked his way, slowly and methodically, through the entirety of The Well-Tempered Clavier, memorizing each piece before proceeding to the next.

The fourth from last book Ziolkowski wrote, Uses and Abuses of Moses: Literary Representations since the Enlightenment (Notre Dame, 2016), holds a special place in his scholarly oeuvre. The book was inspired largely by a 1999 trip he took with his wife to Israel—their first and only visit there—occasioned by his invitation to serve on a team of scholars evaluating the Rosenzweig Zentrum of Hebrew University, Jerusalem. His diary from that trip, two years before his retirement from Princeton, is filled with notations of visits to numerous sites traditionally associated with scenes and episodes in the Bible and various apocryphal scriptures as well: David’s Tomb, the Church of the Dormition, the Temple Mount, the Mount of Olives, the Garden of Gethsemane, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and on and on. As expressed in his diary, his exhilaration from visiting firsthand the various biblical sites with which he was so closely familiar from his readings was tempered only by the distraction of being constantly besieged by aggressive street hawkers and harassed by unsolicited “guides” in Jerusalem’s Old City: “A wholly memorable day,” he notes after an afternoon walk on the Via Dolorosa. “But every attempt at reflection or meditation was interpreted as uncertainty in quest of a guide!” The Moses book is a kind of Hebrew Bible–related sequel to his New Testament–related Fictional Transfigurations of Jesus of forty-four years earlier—and a fulfillment of the musing with which he had closed his Israel diary seventeen years earlier: “Who knows? I may find myself turning to biblical subjects again in my retirement! In the meantime, I need many hours & days to assimilate everything we’ve seen and done in the past ten days. The trip was more than worthwhile, and I had wanted for years to undertake it” (underlines in notebook).

In between Fictional Transfigurations of Jesus and Uses and Abuses of Moses, Ziolkowski published four others that, with them, constitute yet another major branch of his scholarly output. This branch relates literature to religion: Modes of Faith: Secular Surrogates for Lost Religious Belief (Chicago, 2007), which studies the quest by some thirty European writers for meaning in such modern surrogates for religion as art, India, communism, and myth; Gilgamesh among Us: Modern Encounters with the Ancient Epic (Cornell, 2012); Lure of the Arcane: The Literature of Cult and Conspiracy (Johns Hopkins, 2013), reissued as paperback under the title Cults and Conspiracies (2017); and The Alchemist in Literature: From Dante to the Present (Oxford, 2015).

Surprised by the broad range of these books’ subjects, readers often ask about the motives behind the books’ composition. As Ziolkowski would explain, in almost every case he had to familiarize himself with what to him was an entirely new field, and it was this expansion of his own intellectual horizons that gave him pleasure and satisfaction. Always, he stressed, he was working out of a passionate love of learning, and he took gratification from the generous reception most of these books met, even among specialists in the different fields. He described himself as a person prompted by his interest to immerse himself in the given field and accumulate sufficient knowledge to deal with the material competently, from a purely literary perspective. “If I can claim any particular strength,” he once said, “it is the ability to establish connections between unrelated works thanks to some unexpected theme or motif, such as ‘the tell-tale teeth,’ ‘talking statues,’ ‘the infanticide theme,’ and other such offbeat topics.”

Always, Ziolkowski stressed, he was working out of a passionate love of learning.

Throughout his scholarly career, Ziolkowski was often tempted to venture beyond German literature, his “home field” (his term, perhaps recalling his sport-playing youth), into other regions: notably, the reception of classical and biblical antiquity in modern literature; and the interdisciplinary areas of literature and religion, literature and law, and literature and music. His approach, as he was fully aware, differed from that of colleagues who chose to devote many books and articles to a specific figure (e.g., Homer, Shakespeare, Goethe) or period (e.g., Renaissance, Baroque, Victorian) and who were rightfully viewed as specialists in those areas. Ziolkowski, in contrast, never suffered a moment’s regret in his explorations of the various fields he chose to link comparatively and interdisciplinarily to his home territory of German and modern European literature.

In sum, Ziolkowski’s was a life of joy in family; stoical self-discipline, punctuality, and “120 percent effort,” as he termed it, in work; and fulfillment, throughout his life and profession, of the ideal he espoused for students embarking on their chosen own routes in education and life: Bonus intra, melior exi (“Enter good, depart better”), the Latin motto inscribed on the mantel in Princeton Graduate College’s Proctor Hall and copied onto a slate Ziolkowski proudly exhibited at home as a memento from his years as dean.

Easton, Pennsylvania

Theodore Ziolkowski’s Polish Ancestry

Theodore Ziolkowski’s family had its roots in Poland on both the paternal and the maternal side. On Theodore Ziolkowski’s father’s side, the family patriarch was Theodore’s grandfather Józef Ziółkowski (1865–1937), of whom relatives in Poland still today speak with reverence. Józef was born in 1865 in the little village of Ostrowo, near the eastern shore of Lake Gopło. His father was Maciej Ziółkowski, a farmer who had lived in the nearby village of Tarnowo. Maciej’s wife, Marianna, was from the Olszewski family. The name Ziółkowski, though common today in Poland, is not known in the environs of Kruszwica, the town at the northern head of Gopło, where Jozef Ziółkowski later lived and made his name. Józef had one sibling, his sister Maryanna, who married Szczepan Gralak and immigrated with him to the United States, where they settled in Calumet City, Illinois, near Chicago, and had nine children.

Maciej Ziółkowski sent his son Józef to trade school to be trained in business, and then for successive apprenticeships in Lvov and Berlin (at the Max Schultz company)—hence the family’s lasting association with Germany and the German language. When Józef returned, he did not remain in his home-village of Ostrowo but instead settled in Kruszwica, where he married Franciszka Olszewska. Together they had eight children: four daughters and four sons, one of whom was Mieczysław, Theodore’s father. A concert pianist, composer, and teacher who had studied at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin, Mieczysław Ziółkowski taught at the Warsaw Conservatory after World War I. In 1924, at Poznań, he met the great pianist, composer, and statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski and performed his own Tatry suite in a concert honoring the maestro, who took such delight in the performance that he invited Mieczysław to study privately with him the following summer at his Swiss residence outside of Morges.

Two years later, in 1926, Mieczysław Ziółkowski immigrated to the United States to assume a teaching position in the Columbia School of Music in Chicago, where he also gave some well-received concerts. It was there that he met Cecilia Jankowski, likewise a Polish American, and likewise a pianist, and also a dancer, who had grown up in nearby Joliet, Illinois. Mieczysław and Cecilia married and in 1930 moved south to Montevallo, Alabama, where he accepted a music professorship at Alabama State College for Women (today Montevallo University). They spent the rest of their lives in Montevallo, a small town located at almost the exact center of the state. While Mieczysław taught at the college and often traveled to give concerts throughout the southeastern US, from Atlanta to New Orleans, Cecilia gave piano lessons in their home to local young persons. Mieczysław and Cecilia had three children: Theodore, in 1932; a daughter who died in infancy a couple of years later; and a younger son, John, in 1939. Only once was Mieczysław able to return to Poland to visit with family in Kruszwica; he did so in 1937, two years before the German and Soviet invasions, taking with him his wife and young son, Theodore, who as an adult would recall only vague images from the trip. Both Mieczysław and Cecilia died in Montevallo: he, in 1966; she, in 1971.

Author’s note: This genealogy draws heavily upon the Ziolkowski family “Saga” composed by my father for my two siblings and me, following his and my mother’s several visits with his cousin Anna Konik, her daughter Małgorzata Konik, and other Polish relatives in Kruszwica in 2005, 2006, and 2007, and revised with Małgorzata’s kind assistance in March 2007.