Jewish Life in Harbin, China: A Conversation with Jean Hoffmann Lewanda

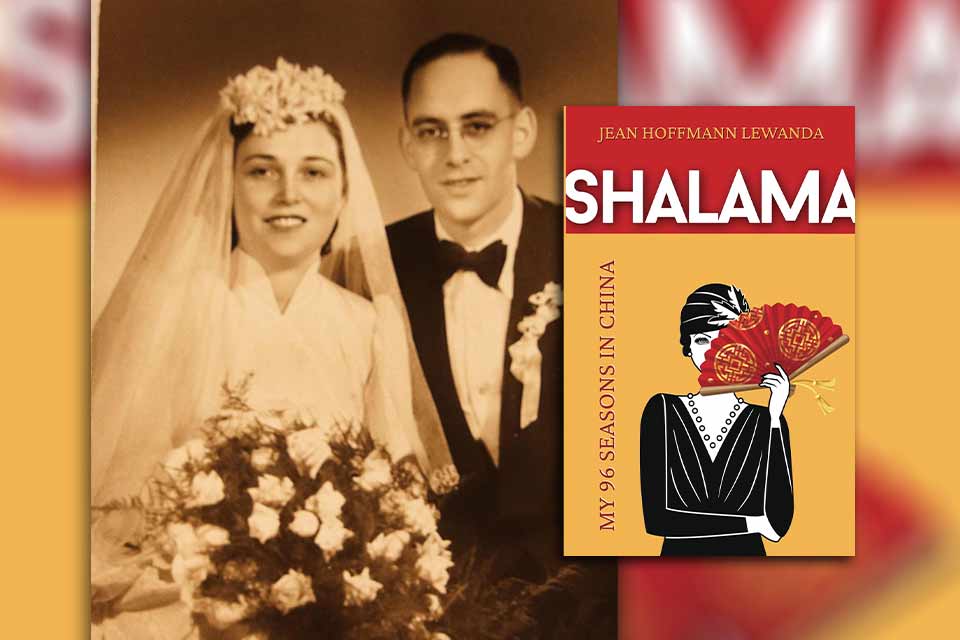

I met the author Jean Hoffmann Lewanda for lunch this past November in New Jersey, not too far from her home in suburban Philadelphia. Jean is the author of a new book, Shalama: My 96 Seasons in China (Earnshaw, 2024), the story of her mother’s childhood in Harbin, China, and young adult years in Shanghai. Jean’s first book, Witness to History: From Vienna to Shanghai: A Memoir of Escape, Survival and Resilience, is an edited edition of her father’s memoir tracing his escape from Nazi-controlled Vienna to the safe shores of Shanghai in the late 1930s. Jean and I originally met online thanks to mutual friends who are historians and the authority on everything Old Shanghai. When we met in person in November, we spoke for hours about publishing Jewish Chinese stories. We expanded this conversation over email.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Thank you, Jean, for continuing our lovely conversation back in November. I don’t remember coming across other authors who have personal connections to both the old Shanghai and Harbin Jewish communities, each of which numbered in the thousands. Your mother was the daughter of Russian Jewish refugees, and your father was an Austrian Jewish refugee. Was it unusual for people in these two Shanghai Jewish communities to marry back then?

Jean Hoffmann Lewanda: By the time my parents met in September 1949, a good portion of the Jewish community had left, predominantly to Israel, America, and Australia. The opportunity to meet anyone was limited. As I think about my family and parents’ friends, most couples were from similar backgrounds, and my parents were the exception. I am guessing language and prejudicial opinions about the status of each community influenced who people chose as partners.

Blumberg-Kason: Although you published Witness to History first, I’d like to start with your latest book, Shalama: My 96 Seasons in China, which came out in October 2024. It’s based on your mother’s story, beginning in Harbin, a city in northeast China that’s now known for its annual ice sculpture festival. It’s very cold up in Harbin, so these sculptures stand strong for the duration of the festival! Harbin is also known for having once had a large Jewish community before World War II. The community dispersed decades ago, but quite a few buildings constructed by Jews still remain, including hotels and synagogues. Shalama—a novel based on your mother’s life—goes into great detail about Jewish life in Harbin in the 1920s and early 1930s. Your descriptions are so vivid, and I can’t think of another Jewish Harbin book that is so comprehensive. How did you research this time and place? And how long did it take you to conduct this research?

Hoffmann Lewanda: I first made contact with Dan Ben-Canaan in 2017. Dan, a resident of Harbin, is responsible for the identification and restoration of the buildings to which you refer. Dan was excited to learn about the many photographs that I had of old Harbin and helped me identify the places and events in the photos. When I visited Harbin in 2019, Dan gave us a tour of the city and the Foreigners Cemetery. In addition, I have read firsthand accounts of life in Harbin published in Igud Yotzei Sin, a publication of the Association of the Former Residents of China, collections of stories that Dan has published and memoirs written by friends of my mom. To answer your question about how long it took to conduct the research, it spanned six years. While writing, I continued to research events.

Blumberg-Kason: I really enjoyed reading about your mother’s schooling in Harbin. This passage has stayed with me: “I loved school even more than I thought possible. We were taught in Russian, but we also learned Hebrew and Japanese. Why Japanese? Because we were still under Japanese occupation; the occupation that started in 1932 didn’t end until 1945 when the Japanese were finally defeated in World War II. One of the stranger circumstances of my life, and one that I regret, is that I lived the first twenty-four years of my life in China, and except for a few words, I never learned Chinese. Maybe this was because Harbin never really felt very Chinese with the overwhelming influence of the Russians and the Japanese.” This really encapsulates the ways in which Harbin was—and still is—unique. With all of its Russian architecture, Harbin still doesn’t look like a typical Chinese city. Did you grow up learning about the history of Harbin from your mother, or was it something you came to as an adult or even when you started writing about your parents’ decades in China?

I had no idea about the unique Russian nature of Harbin until I visited in 2019. I was totally surprised by the Russian/European appearance of the city.

Hoffmann Lewanda: There were certain things I knew about Harbin from my childhood. The stories about summers at the dacha, the brutally cold winters, and what was taught in school were often repeated. I had no idea about the unique Russian nature of Harbin until I visited in 2019. I was totally surprised by the Russian/European appearance of the city. I now find it interesting that on the one return trip to China that my parents took in 1998, my mother opted not to go to Harbin. She said there was nothing familiar left to see there.

Blumberg-Kason: That’s so sad, but I think it’s common for people from all over to not want to return to their former homes after many years and many changes. Turning to the framework of your book, I really like the way you structure Shalama and find that I’m now drawn to books with many short chapters. Perhaps it’s because we’re living in an age with instant information and twenty-four-hour news at the touch of a screen. Everything is so immediate these days, and maybe that’s why I appreciate short chapters. How did you decide to use this structure, rather than writing traditionally longer chapters? Did other books serve as a model for this structure?

I enjoy books with short chapters too. In our busy lives, it allows one to pick up a book and make headway in the story in a short period of time.

Hoffmann Lewanda: I agree with you completely, Susan. I enjoy books with short chapters too. In our busy lives, it allows one to pick up a book and make headway in the story in a short period of time, allowing us to return whenever we find a few moments. Short chapters also help to keep the reader engaged. It’s the feeling of “Where is this going? What’s next?” Also, I have read many historical novels in the last several years that involve flashbacks and conversations with a member of a younger generation. This structure lends itself to short chapters and certainly influenced the structure of Shalama.

Blumberg-Kason: Your mother left Harbin in 1940 as the economy and quality of life deteriorated under the Japanese occupation that began in 1932. The natural—and easiest—place Harbin Jews could flee to was Shanghai, which also had a Russian Jewish population in the thousands. Shanghai comes alive, too, in your first book, Witness to History, which is your father’s story and actually a memoir he had written of his escape from Vienna to Shanghai and the life he made for himself in China, including meeting and marrying your mother. Can you discuss how you discovered your father’s manuscript and when you decided it should be published?

Hoffmann Lewanda: My dad finished his memoir, solely to be shared with the family, in 1998. He provided my brother and me with a hard copy and a floppy disk from an old Brother word processor. Several factors influenced how long it took to publish it: work, children, and finding a program that could convert the text into an editable format. It also came as a complete surprise that there was interest from a publisher after Dad’s passing in 2010. I assumed that one day I might self-publish the manuscript, but when Liliane Willens, author of Stateless in Shanghai, read it. She took it to Shanghai, and Graham Earnshaw of Earnshaw Books picked it up. The pandemic turned out to be a blessing in that it provided so many hours to do something new, which led to the November 2021 release of Witness.

Blumberg-Kason: Witness to History is a memoir and therefore nonfiction, whereas Shalama is a novel based on your mother’s years in China. Did you find it difficult to transition from nonfiction to fiction? What were your biggest surprises in writing fiction, and do you prefer fiction over nonfiction or vice versa?

Hoffmann Lewanda: Since I was the editor of Witness, I am not really sure I can say I have written nonfiction. I think the strength of Witness is that it is a firsthand account with the emotional impact that can only be conveyed by someone who has experienced the events and is relating it through their lens. When I think about Shalama and what I hope will be my next book, also about a Jewish European woman living in China but during an earlier era, I believe historical fiction is the way to go. Since I haven’t lived it, I enjoy trying to understand the time frame and getting into the heads and hearts of the characters.

Blumberg-Kason: We spoke over lunch about film adaptations, which is how I always like to end interviews. If you had to cast actors for Shalama, who would you pick for your mother and father? And if you could take a role in the film adaptation, who would you play?

Hoffmann Lewanda: I think Felicity Jones and Joseph Fiennes might be appropriate actors to play Mom and Dad. They are both European and I think would be well cast in a period piece. If I could have a role, it would be my mom’s school friend Musia, mostly because I observed Mom being a very good friend throughout her lifetime and would know how to respond to her character.

Blumberg-Kason: Thank you so much, Jean, for taking time to chat more about your books. They are both vital to the literature on Shanghai and Harbin Jewish life a century ago.