“In History to My Barest Marrows”: A Conversation Between Yinka Elujoba and Emmanuel Iduma

Emmanuel Iduma’s The Sound of Things to Come was first published as Farad in Nigeria. Its unusual style and ambition instantly separated it as a brilliant first novel. In this conversation, writer Yinka Elujoba talks with Iduma about The Sound of Things to Come and other probings on writing.

YINKA: Let us start with the idea of a reissue. The Sound of Things to Come was earlier published as Farad. You know, when I think of a reissue, I think of a second coming of something or someone, and strangely, I think of this in some biblical context. What do you think?

EMMANUEL: That’s interesting, because I’ve never thought of it that way, as a second coming. The idea to reissue it wasn’t originally mine. I didn’t necessarily aspire to have it reissued in the US. But I left the possibility open. When I moved here, I became friends with Shaun Randol, whose imprint published Gambit: Newer African Writing. He had always wanted to publish writers who were relatively unknown in the US. However, I must tell you that when I held the new edition for the first time, I felt something was different, almost on an elemental level. Yes, the title had changed, but beyond that, it felt like some new light had gone into it.

YINKA: Recently in a conversation with a photographer, she told me about body and mind memory from her own past experiences—and I bring up the body and the mind because in The Sound of Things to Come there is the subject of abuse and recollection. As a response to impulse—in case you’ve never thought of these things before—what do you think of body and mind memory?

EMMANUEL: I’m very interested in how dancers speak about their work. The choreographer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer said, “You have to test the fitness of your instincts.” Sometimes I don’t necessarily work with a theme in mind, responding instead to the kernel of an idea or an event. I was fascinated about how General Sani Abacha, who ruled Nigerian in the 1990s, was rumored to have died sleeping with an Indian woman. I became interested in this woman and how her mind changes as a result of a physical act. When I was writing, I didn’t think about how the story would fit into major themes like body and mind memory.

YINKA: It is interesting to me that you’ve mentioned Abacha. I like how his spirit hovers around the book in a stark manner. I must have been around eight when the man died, just finishing from primary school. I remember clearly returning from school to find everyone on the street singing and dancing. I didn’t have the slightest idea as to why anyone would rejoice because of another person’s death, but I remember I was so excited I ran and leapt across some huge gutter on the street. What do you make of the man? You’ve portrayed him in quite an interesting manner, with one of the characters calling him “a good man,” which would be quite an abominable thing for anyone to say publicly in Nigeria of Abacha. Was there anything personal, no matter how loosely?

EMMANUEL: I lived in the capital Abuja when Abacha was in power. If you drove past the Aso Villa and pointed at it, you could be dragged down from your vehicle, flogged, even treated as a spy. It wasn’t unusual to see people being punished by soldiers. It was an intense time. However, I don’t think I wrote about the Abacha most Nigerians know. Nigerian history portrays him as a taciturn guy, who hardly spoke in public, but who was a good, loyal soldier. He played a key role in making sure Ibrahim Babangida wasn’t toppled in the early ’90s. I didn’t know this much when I was writing the book. I worked mostly with impulse and with what I could project on the happenings at the time.

YINKA: I imagine that in writing about the human mind and things relating to some form of psychology you would have done lots of research. And because of how vast the human condition can be, I’d also like to imagine that you changed after writing the book in some way. What did you learn?

EMMANUEL: I didn’t do a lot of research. It would be fraudulent to say I did. But on a technical level, for example, I found out the kind of stories I’m interested in. I’m interested in the combination of the metaphysical and mundane. I’ve been told the novel is not Nigerian. I’m fascinated by what that could mean. But I think there’s an expectation that Nigerian stories revel in the sociological. The closest you get to that is the election in the second chapter. The other stories contain a kind of metaphysics that incorporates and expands on the realistic. These are the things I understood better after writing the book. Not necessarily the human mind.

YINKA: I’ve always been a proponent for how reality can be fiction’s most potent supplement. Evidently, some of the characters in The Sound of Things to Come, like Abacha, for example, are real-life characters. Some other parts of the book also point to what may have been occurrences in your life, for instance a son’s journey to Mali for a photography expedition just as he’s done with law school, in a similar fashion with how you’d left for the Invisible Borders road trip. What is the place of reality in your fiction? How do both of them intersect for you?

EMMANUEL: I’m scarcely interested in making these distinctions. This is not to argue for a carelessness in handling facts—I’m not interested in making someone’s life what it’s not. It can be problematic sometimes, but I always want to use reality to provide—to use your word—a “supplement” for fiction. I knew I was writing about myself in some way. I also knew I was writing about my father. It wasn’t necessarily the truth, but I speculated on his ideas of what I could become. I also speculated on what I was becoming. What were the probabilities that our separate ideas could clash? The possibility of projecting on reality is what I find promising.

YINKA: It was interesting to read a book that could make tensions between simple relationships like sisters or father and son some of its central concerns. And these differences in the kind of stories in The Sound of Things to Come remind me of the stereotypical eye with which African literature is seen. By the way, I use the term “African literature” loosely, because it’s a keenly debated phrase in many circles.

EMMANUEL: It could be a stereotype, but it could also be the blighted sense in which we define our affiliations. An insufficiency of categories, perhaps. People always use what is available to them to talk about something new. For example, I was at the Brooklyn Book Festival signing books. A white guy—eventually I find out he’s Russian—was with a black guy. He picks up my book. It’s obvious he wants to buy, but he’s unsure. The black guy asks him what the book is about and he says, “Africa.” That seems to say a lot about how these books are categorized, what the entry point is, regardless of the range of their explorations.

The work of infusing African Literature with more than just the current stereotypes is a long, arduous one. Most people offer cheap consolations and solutions. It’s likely going to be a question of considering alternative origin stories. You could begin with Amos Tutuola, for instance. Or Cheikh Hamidou Kane. Or Yambo Ouologuem. Or Mohamed Choukri. Or Bessie Head, or Ama Ata Aidoo. Or, to be scandalous, Paul Bowles.

YINKA: We are similar in some regard: we both write essays, are interested in writing about images and art, and we write fiction. So perhaps I should ask you a question I find difficult to answer when people ask me. Do you think being an essayist/art critic informs the way you write fiction? Do you think it makes you approach fiction differently in any way?

EMMANUEL: Certainly. There’s the essayist in me, and there’s the novelist in me. Both interact. I like the idea of a rich twilight, and there’s certainly one in my writing. I recall that when this book was Farad, a reviewer wrote to say he felt the stories were essayistic, and this was one of the problems of the book. That’s quite laughable. Isn’t the novel a large enough boat to contain the essay? Isn’t the essay a territory—and you’ll find this if you go back to Montaigne—in which storytelling and metaphysics can tread? I’m happy to approach fiction as an essayist. My favorite novels aren’t so hierarchical in their aspirations. They roam across all possible forms of narrative.

Isn’t the essay a territory—and you’ll find this if you go back to Montaigne—in which storytelling and metaphysics can tread? I’m happy to approach fiction as an essayist.

YINKA: I find it amusing that someone would consider a novel reading like an essay to be a problem. I imagine that for some, there has to be a plot, a beginning, an end, some climax. This brings me to the question of how we think about readers when we write. I remember Ivan Vladislavić in an interview saying, “I obviously consider the reader to the extent that I hope someone will read what I’ve written and I expect them to get something from the exercise. But I cannot say that I think about this reader when I’m working.” What do you think? How much do the readers matter? Is the story first of all for yourself?

EMMANUEL: No, the story belongs to the story and the essay belongs to the essay, which is one point Vladislavić makes in that interview. But this is a tricky thing to assert, because there’s the trinity formed between the text, the writer, and the eventual reader. Thinking about a reader perhaps helps us to continue doing the work, like pitching forward. Yet there’s no such thing as an identifiable reader. All our assumptions rest on speculations, or metaphors. For instance, my ultimate reader is a seven-year-old boy. In response to his teacher who said, “Don’t swallow your words,” he said, “When I swallow my words they taste like air.” My writing is directed at the intelligence of that child.

Perhaps I am an audience for my writing. Not audience as in reader, but in what I grow into after a long, prolific writing life. Increasingly empathetic, and reflective.

YINKA: As a way of wrapping up this conversation and perhaps opening up a future one, in your present work, what do you think you’re focusing on that’s different from what you’ve done in The Sound of Things to Come? Has there been a leap—and I use the word quite dangerously —in your concerns as a writer?

EMMANUEL: The novel I’m beginning to work on, I like to think, expands on the ideas in Sound. I’m still interested in the church as a place of contested power, but this time across generations of preachers. The leap, to use your dangerous word, is in my headlong engagement with the historical. I always recall a line from a Glissant poem: “I am in history to my barest marrows.” The body remains a pressing concern for me, the body in Christianity.

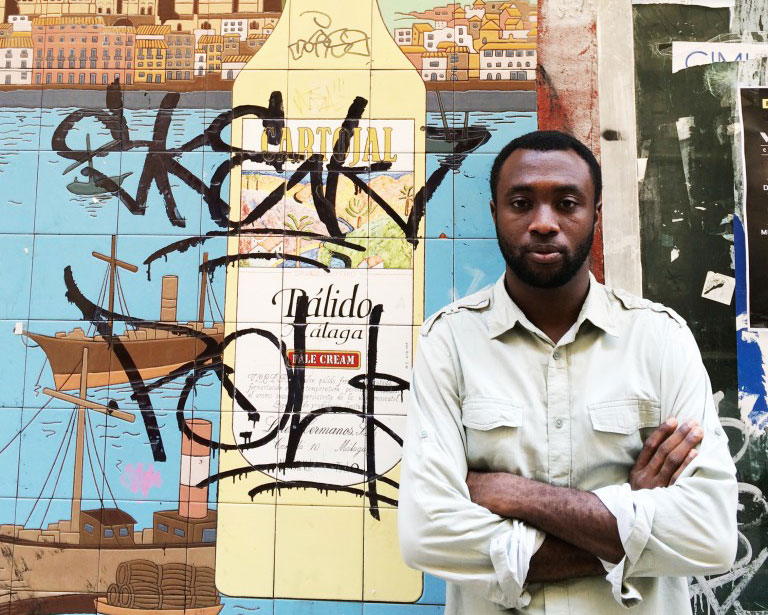

Emmanuel Iduma was born and raised in Nigeria, where he trained as a lawyer. He received an MFA in art criticism and writing from the School of Visual Arts, New York. He is a co-founder of Saraba Magazine and co-editor of Gambit: Newer African Writing.