“All Art Is History”: A Conversation with Parul Kapur

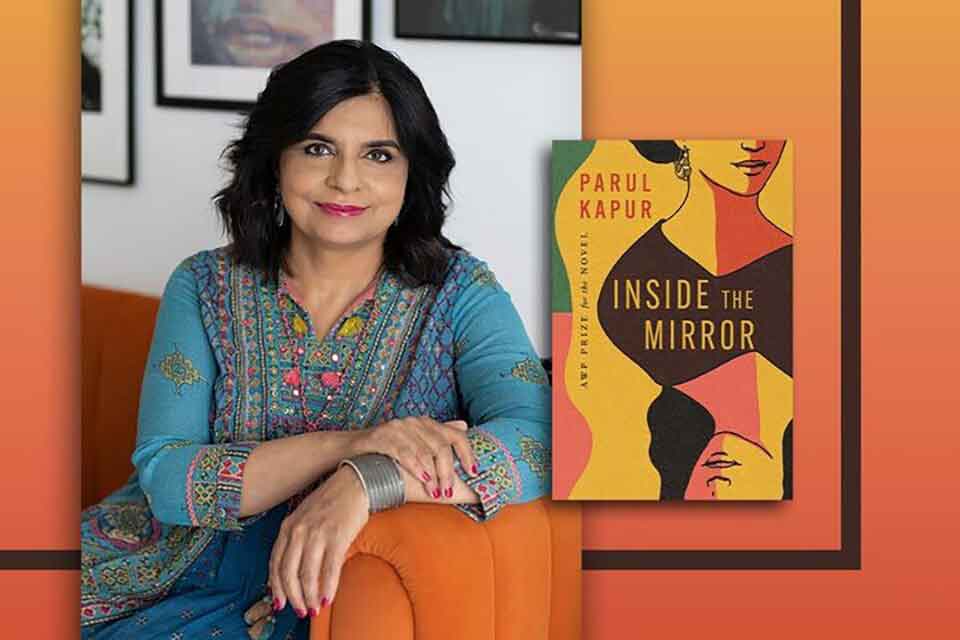

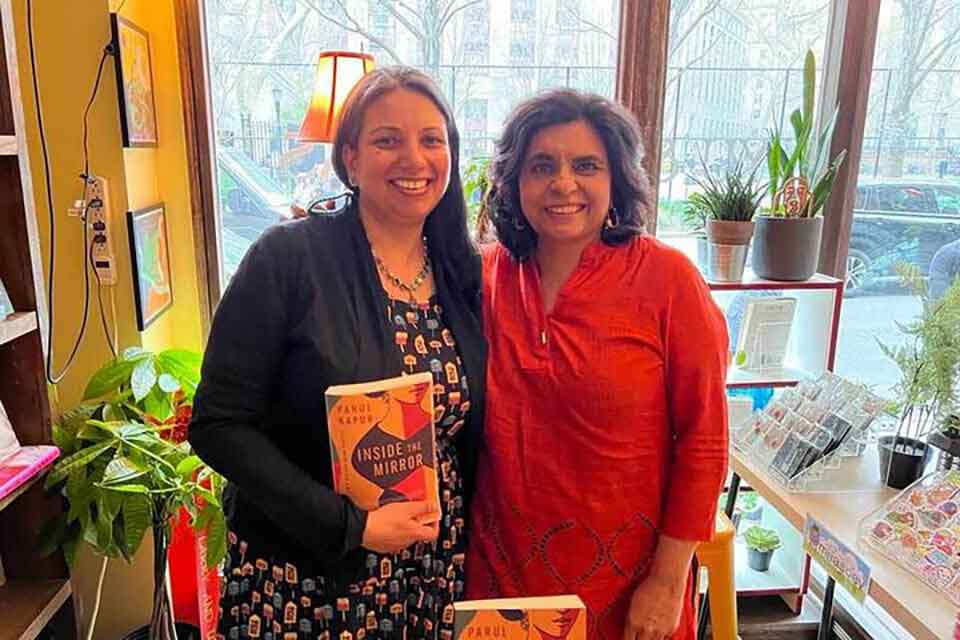

On March 26, 2024, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop co-sponsored an event at Yu and Me Books to celebrate the New York City launch of Parul Kapur’s debut novel, Inside the Mirror (University of Nebraska Press), winner of the AWP Prize for the Novel. Parul was born in Assam, India, and raised in the United States. Her fiction appears in Ploughshares, Pleiades, Prime Number, and more. She has contributed articles and reviews to the New Yorker, Wall Street Journal Europe, Esquire, Art in America, Slate, Guernica, Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Paris Review. She was a press officer at the United Nations in New York and worked as a reporter at the city magazine Bombay in India. She holds an MFA from Columbia University and lives in Atlanta.

On March 26, 2024, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop co-sponsored an event at Yu and Me Books to celebrate the New York City launch of Parul Kapur’s debut novel, Inside the Mirror (University of Nebraska Press), winner of the AWP Prize for the Novel. Parul was born in Assam, India, and raised in the United States. Her fiction appears in Ploughshares, Pleiades, Prime Number, and more. She has contributed articles and reviews to the New Yorker, Wall Street Journal Europe, Esquire, Art in America, Slate, Guernica, Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Paris Review. She was a press officer at the United Nations in New York and worked as a reporter at the city magazine Bombay in India. She holds an MFA from Columbia University and lives in Atlanta.

Parul and I met almost twelve years ago in an online writing class led by Minal Hajratwala. The two of us and our third comrade, Geeta Kothari, have kept in touch ever since, writing a weekly email to each other with an update on our writing processes. For me, this weekly connection has been a buoy for my own work. It is an honor to bear witness to another writer’s artistic practices. I was delighted to be in conversation with Parul about her extraordinary novel and the many invisible labors behind it.

Inside the Mirror is a story set in 1950s Bombay in post-independence, post-Partition India. Parul’s writing is steeped in research while her language is lush and lyrical and full of emotional insights. We follow the story of twin sisters, Jaya and Kamlesh, who each desire to pursue art while they navigate societal and family expectations of them. It is a story of multiple twinnings—not just Jaya and Kamlesh but also the simultaneous birth of the modern Indian art movement at the same time as independence and the twinning of these sisters pursuing self-rule and figuring out their own identity at the same time as their nation.

Sangamithra Iyer: Parul, I wanted to begin by asking about origins. What was the original inspiration for this project?

Parul Kapur: The inspiration for my novel was multifold. Very practically speaking, I was in the MFA program at Columbia University many years ago, and in the midst of the program, I showed a bunch of short stories I’d written to an agent. She liked them, but she said you should really have a novel because short stories don’t sell. I think a lot of people still give that advice today. So, the practical impetus was that I should write a novel.

The other inspiration was the year I’d spent in India before I started my MFA. I went to India and thought I might want to move back there because I had come here [to the US] as a child with my parents. I knew I’d be a writer, and journalism was practical, so I got a job at Bombay magazine. It had a very young staff. They were all just out of college like me, and I spent a year there. It was very impactful. I did all kinds of stories all over the city, from going to movie studios to visiting a slum colony to writing about a colony of dancing girls. I would have loved to stay there except that I really missed my family in the US. So, I came back. The novel is steeped in that year in Bombay, even though I wasn’t there in the 1950s, obviously.

The twin sisters come from these young twins I met when I lived in Connecticut. There were no other Indian families in the 1970s living in our town in Connecticut, let alone any other people of color. But then an Indian family moved into town, and they had twin daughters, who were only six. I was about sixteen when I met them, and they were so cute and so clever and asked me lots of questions about this little town. I was very lonely in that town, and I thought if you had a twin sister, you wouldn’t feel lonely. So those were some of my inspirations.

Iyer: One of your characters gives a speech where he says, “All art is history. . . . The paintings in this hall are all beautiful and varied contemplations of a single idea: Who are we now? How do we see ourselves now that those who occupied our land and enslaved us are gone?” I think your novel also has these beautiful and varied contemplations of these questions.

In one essay you write: “My understanding of Jaya, the young painter at the center of my novel, was intuitive. She wasn’t so different from me in her determination to become an artist. What took years for me to understand was the broken world she was born into.” Can you talk about your process of researching this history and recovering this world these twins were born into?

Kapur: I worked on this novel off and on for almost twenty-five years. And then I put it away for ten years. It’s been my lifetime’s work in a sense, and then it won the [AWP Prize for the Novel] contest. I had to do a ton of editing on it. The manuscript was much longer, so there was a lot of cutting involved. Writing it was a very protracted process and then editing it a very intense, short process to bring it to publication.

What took so long to understand this history? First, I will say that I didn’t even know I had an interest in history. But my father was always recounting stories from the past, especially in India. Anything that would happen in our home in Connecticut or in our lives, anything significant would spark a memory of his, and he would say, “Oh yeah, when I was in Lahore, this happened . . . and that happened.” So maybe I was almost conditioned to appreciate history, even though there was a time when I was not that interested in his stories—I was young, and I was more interested in my life in the present. But I think hearing his stories got me very interested in the past. And in India, there is a very strong oral tradition of learning, so I’m wondering if I was genetically engineered to connect to oral storytelling, because then I became a journalist. And the way that I understood things was by interviewing people. I approached my novel in the same way.

When I was younger, I was absorbing my father’s stories almost subconsciously. Then when I started the novel, I deliberately sat down with him and would ask him questions. Even simple questions, like “In India, did a BA take four years or three years?” would prompt him to go off on to some other stories about what happened, maybe, when he was at Commerce College in Delhi, which led to stories about his family. Why were they in Delhi? Because they had fled Lahore during the Partition. And then I started to ask him much more pointed questions.

Similarly, I spoke to artists who had been part of the Progressive Artists Group, which I fictionalized as Group 47, because the Progressive Artists Group in Bombay was founded in 1947. There were some associates of the Progressives who lived in New York. A lot of those artists left India in the 1950s and thought they could make their careers in the West. And they didn’t really flourish here, nor did they flourish in India. Now their paintings sell for millions of dollars at Sotheby’s auctions, but in their lifetime, they didn’t see much success. I met with an artist named Mohan Samant here. He spoke to me about what the art movement in India in the 1950s had been like. And you know, similarly, [I had conversations with ] Indian doctors here who had studied in Bombay. Jaya is a medical student, and there are scenes in the hospital. A lot of people who have come here can remember the past in India much better than the people in India, who have seen so much change. They can’t remember the past as clearly so, in that way, I was lucky to be here even though it was hard to find the people that I needed. But I did a lot of interviewing.

A lot of people who have come here can remember the past in India much better than the people in India, who have seen so much change.

Iyer: It’s very palpable, the ripples of Partition that are in the pages, and how you capture the tensions in the society. You and I were talking earlier about how I was interested in E. J. Koh’s scholarship on the Korean concept of han—the sort of deep collective sorrow that comes from legacies of colonialism and having a country divided. There’s a lot of resonance with Partition. And I don’t know if there’s a similar word that you’ve encountered, but how were you capturing the various manifestations of this?

Kapur: There was this very deep sorrow about the tragedies people had suffered. I think most of you probably know that India was partitioned at the time the British left in 1947. The western and eastern sides of the Indian subcontinent became Pakistan, West Pakistan and East Pakistan. In terms of my personal story, my father’s family lived in the part that was suddenly declared to be West Pakistan. His family lost everything. And they had to flee. I heard so many stories from my father, nothing in any kind of chronological order, but just: “So and so left with his daughters. He sold everything to get twenty thousand rupees to get his adolescent daughters on a bullock cart.” And my dad’s uncle was afraid his daughters would be raped on the way trying to get into India. And what would he do? How would he protect his daughters? He was very afraid that something terrible would happen to them and he wouldn’t be able to protect his daughters, which is the duty of a father, especially in a patriarchal society.

I heard many such stories. And it took me a while to figure out what my father would never say. The story, obviously, is tragic, but he didn’t show much emotion when he told me these stories. He would just present them as kind of neutral facts, because I think it was too much to be emotionally involved in it all over again. I think that collective sorrow is contained in all his stories and the stories of other relatives I also spoke to.

It took me a while to figure out what my father would never say.

Iyer: In addition to this outer world, you do such a marvelous job of capturing the inner world of these twins and the enormous family burden placed on them. One of the twins reflects the following:

He didn’t know that inside you were made of your obligations to other people, your allegiances and your debts to them—these were the connective tissues that held a person together. He knew nothing about India. Knew nothing of Indians. He had lived here for years, but he didn’t know what it meant to be part of a society where you were threaded together with everyone else. . . . A girl pulling herself out of the web of her family could cause the entire web to tear and collapse.

You show that this web can collapse when these women pull away from their obligations, but also when they pull away from their artistic desires. How did you think about this fragile web as you were writing this book?

In India, there’s almost no concept of the individual. You’re always part of a group.

Kapur: India is completely different in orientation to the US, which is much more individualistic, although I think people here are now recognizing the importance of community and groups. But in India, there’s almost no concept of the individual. You’re always part of a group.

When I was living in Bombay for a year, I felt very obligated to my parents’ friends, feeling like I should call them because I’m here in the city and they would expect me to come over and meet them. For Jaya and Kamlesh, growing up in the 1950s, society was even more conservative and traditional. For a girl like Jaya to leave her parents’ house and move in with a female mentor is a scandal, because you’re never supposed to leave your parents’ house until you get married. And if you do something that no one is supposed to do, it’s not just accepted as, “Oh, well, she’s just being rebellious,” as it would be here. It is like you’re breaking laws. You bring great shame on your family. They lose their position, you lose your position. You lose your reputation.

It’s a collective society where the norms are known by everyone. And everyone is supposed to follow those rules and it’s all good. But if you violate any of those rules, even if it doesn’t affect other people directly, your reputation—which is your worth in society, your worth as a person—is destroyed. And in that way, you can destroy your whole family, too.

Iyer: I think it’s also really interesting about the tensions happening in the art movement that you depict, of figuring out the identity of the modern artist and what that means. What do you draw from? Western influences? Do you go back to Indian traditions? Kamlesh is studying a dance that was banned by the British, so dance is like a reclamation.

Another character reflects, “What I’ve come to realize . . . is that we’re a country of art makers. There’s nothing so unusual about what you or I or any of the Group 47 artists are doing—it’s in our blood, making art.” Do you view art-making as our ancestral inheritance?

Kapur: I think art is very much a part of the cultural fabric in India. If you go to villages, even among very poor people, there is an emphasis on decoration, adornment. I was in South India, where the horns of the cows were painted in different colors. They might be red, they might be turquoise. Even on mud huts, people sometimes draw around the doorways. Part of it might be to bring good spirits and good vibes to the house, but there’s always this emphasis on art and decoration. India is—or at least it was—highly stratified. Artists used to belong to clans, right? You came from a tradition or a clan of artists. Temple dancers, for instance, were part of a lineage of temple dancers that was their profession, in a sense. Other people didn’t just enter that tradition, and then the British disrupted everything The idea of an individual deciding to become an artist was not known. That’s a Western concept. And that’s why what these sisters are doing is so unusual.

June 2024