Who Decides Good Grammar?

The author weighs the benefit of grammar guides’ standardization of language against their history of neglecting the language of underprivileged groups, comparing this tension to the concepts of prescriptivism and descriptivism.

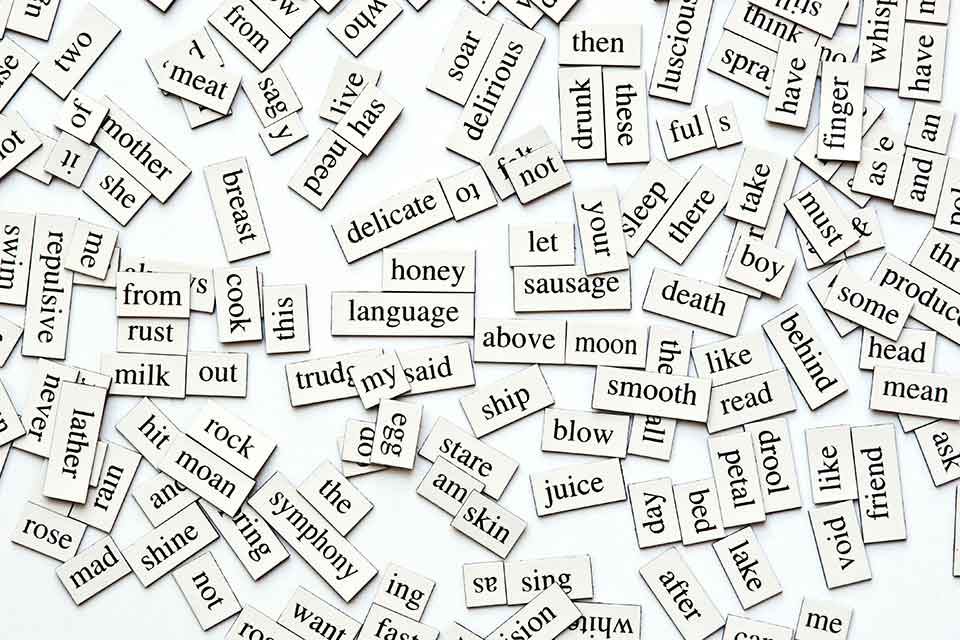

Everyone has an idea of how language should sound or read. Even the most grammar-flexible people tend to prefer language that sounds like their own. Some like to record and debate the “proper” use of language on the basis of consistency and readability. We call these people prescriptivist for their interest in defining and explaining a right and wrong way to speak or write. Other people like to explore and record everything language has to offer in all its clever inventions and tedious idiosyncrasies. We call these people descriptivist for their dedication to revealing language’s most messy, honest, and personal forms.

Prescriptivism and descriptivism are useful concepts to help articulate the discrepancy between the nature of language inviting invention and how language variation is often restricted by culturally dominant groups in a society. Linguists, the most notorious descriptivists, typically engage most with spoken language, but this disregards the fact that written language plays an important part in navigating life, whether through books, emails, paperwork, text messages, websites, etc. Just as with spoken language, people develop preferences for certain styles of writing and make assumptions about people based on the way they write. For this reason, it’s important for readers, writers, and editors to interrogate their unconscious preferences for different styles of writing and the biases that govern them.

In the US, with the rise of literacy and print culture in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, some members of society—in the Western world this means conventionally educated white men—found it important to write usage guides.[i] These guides set down rules for how words, punctuation, and style should be used and in what context. The first influential guides were written in the eighteenth century, laying the foundation for and inspiring new editions and guides into the twenty-first century. Once a rule becomes widespread, guidance changes slowly as students are taught the “correct” way to write and pass that on to the next generation.

A perfect example of this is the double negative. Historically, double negatives were accepted and used by such authors as Chaucer and Shakespeare, until Bishop Robert Lowth wrote the influential A Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762), in which he argued that, like math, two negatives cancel each other out. Never mind that language is not math and in other languages negative agreement, or negative concord as linguists describe it, is not only grammatical but required for “proper” grammar. For example, take the phrase for “I don’t know” in French, Je ne sais pas. It literally translates to “I not know not,” where ne and pas work together to negate sais. The idea of double negatives being improper in English was picked up in the grammar guide published by Lowth’s student, Lindley Murray. His book, English Grammar, was first published in 1795 and has since gone through almost fifty editions.[ii]

Speakers and writers of nonstandard varieties of English find themselves the subject of stereotypes and descriptors like lazy, uneducated, or ignorant due to their nonconformity.

Many grammar rules originating in pre-twentieth-century usage guides have been reiterated throughout the years and taught to children (note: children who were, by privilege or by force, a part of the conventional education system) who then grew up to reinforce and reiterate those rules by using them in everyday life and in media. In the West, socioeconomic class divides give privilege to wealthy, educated white people and underprivilege most others. The socioeconomic group with the most power in a society is going to have the greatest control over what variety of a language is accepted in educational institutions and what style is used in printed media. Speakers and writers of nonstandard varieties of English find themselves the subject of stereotypes and descriptors like lazy, uneducated, or ignorant due to their nonconformity. They are often forced to learn to communicate using the standard variety to find success in society, further reinforcing the perception of the standardized variety’s primacy.

Standardization of a language typically coincides with an attempt to halt language change and control language variation.[iii] Prescriptivists justify this because the stated goal of usage guides is to clear up confusion and identify the most prominent usage of words, grammar, and style that can be used to enable communication across many groups. This is reasonable because language variety can differ greatly by social group and region. Languages also change quickly among young people, an evolution exacerbated by the internet and quickly evolving platforms and trends. Grammar usage guides change slowly to avoid the use of words and phrases that will die out within the year.

Lexicographer Bryan Garner argues in the preface to the fourth edition of Garner’s Modern English Usage that linguists are overzealous in encouraging the use of new varieties. Garner writes that "linguists may take the long view, but good usage depends on the here and now.” He speaks to a feeling among prescriptivists that standardized language serves as a buffer against the anticipation of future evolution as opposed to the way language—meaning language across the majority of speakers rather than localized social groups that develop their own specialized, in-group variety—actually changes, which is slowly.[iv]

On the surface, it is agreeable that most would prefer mass communication to be done in a style everyone is familiar with, but an issue arises when considering who gets to decide what style everyone must use to navigate society successfully. Underprivileged social groups do not often see their style represented in printed writing, save for print produced by independent presses. The rise of the internet, however, represents a change in this trend, allowing anyone to write posts using whichever variety they choose. It’s unsurprising that written language varieties have begun evolving so rapidly, with the increase in contact between groups across class, age, and region facilitated by the internet.

Dictionaries, too, fall prey to prescriptivism. On the surface, they are fairly descriptivist in that their primary goal is to describe how words are being used by the majority of people both in language category and meaning. However, the editors of dictionaries make choices about which words are included and which are excluded. Some words are included but are labeled “nonstandard.” Exclusion and exclusionary labeling represent a more subtle way of prescribing language use by not providing a full account of how language is used and shaping readers’ perception of “proper” word usage.[v]

Grammar guides and dictionaries ultimately have a hand in controlling language use and play a part in reinforcing societal power structures by identifying and defending a standardized language variety.

Grammar guides and dictionaries ultimately have a hand in controlling language use and play a part in reinforcing societal power structures by identifying and defending a standardized language variety. Standardized language is defined in opposition to nonstandard varieties and, when prescribed a moral value, shapes perception of social groups that do not use the standard variety. While guides and dictionaries represent a beacon for consistency and reliability of communication, they also exclude language varieties belonging to people who have not historically been involved with their creation. It is the duty of any writer, editor, or reader who believes in widening their perspective of the world to understand that the form of written language plays an important part in its message, especially when its form does not conform to convention.

Rejection of nonstandard forms of writing limits a writer’s and reader’s imagination and narrows the possible fields of communication. Human experience is so broad and varied that it is a disservice to narrow the ways in which it can be communicated.

University of Oklahoma

[i] Scott E. Casper, “Print Culture,” in Encyclopedia of American Studies, edited by Simon J. Bronner (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018).

[ii] Anne Curzan, Says Who? A Kinder, Funner Usage Guide for Everyone Who Cares about Words (Crown, 2024), 21–29.

[iii] Rosina Lippi-Green, “The Linguistic Facts of Life,” in English with an Accent: Language, Ideology and Discrimination in the United States, 2nd ed. (Routledge, 2012), 5–26.

[iv] Bryan A. Garner, “Essay: Making Peace in the Language Wars,” in Garner’s Modern English Usage, 4th ed. (Oxford University Press, 2016), xxxiii–xlv.

[v] Rosina Lippi-Green, “The Standard Language Myth,” in English with an Accent, 55–65.