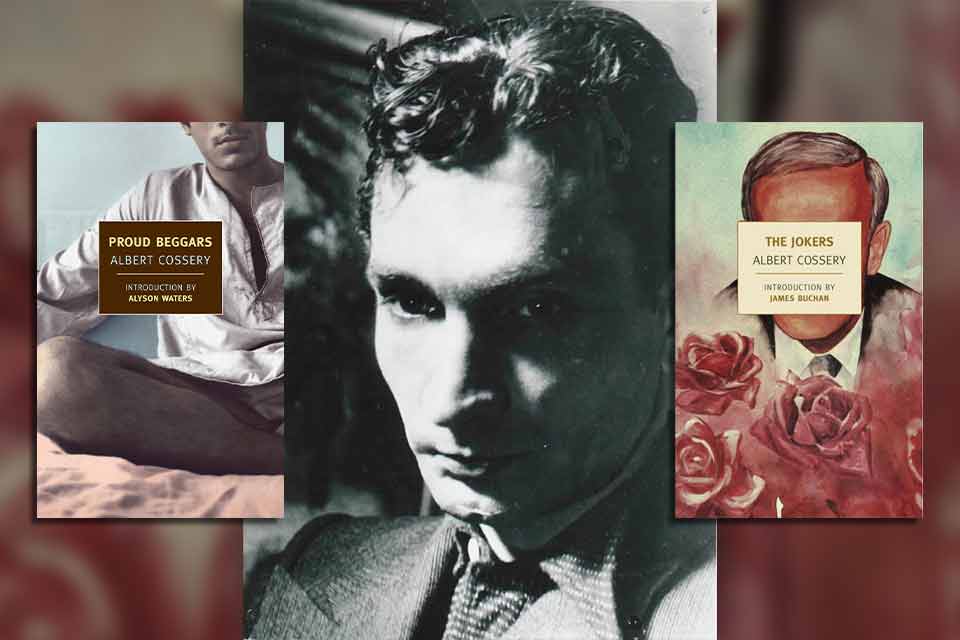

“The Egyptian Joker”: Remembering Greek-Levantine Egyptian Writer Albert Cossery

The end of June marked the anniversary of the death of Albert Cossery (1913–2008), a French-speaking Egyptian writer who is not particularly famous, but whose work will still delight readers with his sense of the absurd, satirical observations about power, poverty and corruption, and sly humor. Cossery was born in Cairo in 1913 to a wealthy Greek Orthodox family, who emigrated from Syria during the end of the Ottoman Empire. Like many Christians in Egypt at this time, Cossery was sent to a French school. With a strong command of French, he left Egypt when he was seventeen for Paris in 1945 and did not return. Instead, he became a vagabond, living in a Paris hotel for sixty years—surviving on occasional royalties.

While a few of his novels have been translated into Arabic, he has not been overly celebrated by the Egyptian literary establishment. However, lauded in France, in 1990 Cossery was awarded the Grand prix de la francophonie of the Académie Française and in 2005 the Grand Prix Poncetton de la SGDL. Cossery, who was influenced by the Egyptian surrealist movement and the French existentialists, wrote about those on the fringe of society: pickpockets, street artists, beggars, prostitutes, peanut-sellers, and revolutionaries. As he said in a rare interview in 1991, “Those who are barefoot will tell you extraordinary things about life and the world.”

Cossery wrote about those on the fringe of society: pickpockets, street artists, beggars, prostitutes, peanut-sellers, and revolutionaries.

Although he was ninety-four when he died, he only wrote eight novels. Les Fainéants dans la vallée fertile was his first novel, published in 1948. Laziness of the Fertile Valley was translated into English by the respected novelist William Goyen and published by New Directions in 1953. Born into a family who owned land in Damietta, young Serag—the main character in this novella who yearns to escape the “pernicious languor” of his family’s run-down villa—seems close to the author. The novel takes place in an unidentified Egyptian countryside and focuses on the intrigue within an Egyptian family, whose main activity is sleep! (I am reminded of Luis Buñuel’s 1962 film The Exterminating Angel, which satirizes Spanish aristocrats who hold themselves hostage in a mansion because they fear the outside world. They even start drilling a hole through the bricks to escape even though the door is wide open!) Serag’s two brothers, Galal and Rafik, are the other sleepers, as well as his father and Uncle Mostapha, who frittered away his inheritance.

The sleepers are forced to wake when their father, who has a hernia the size of a watermelon near his genitalia, is plotting a marriage to a beautiful young girl because of his “desire for renewed youth.” The threat of a wife might destroy their bachelor routine. The only women in the novel are Imtissal, Rafik’s previous lover (a prostitute); Haga Zahra, the obese matchmaker; and Hoda, the maid, a distant relative who is harassed by most of the men in the family. Serag’s desire for adventure is so great that he even feels jealous of the impoverished young urchin, Antar, who is trying to kill birds with a slingshot so that he can sell them. Serag dreams of working in the unfinished factory that has long been abandoned. When he does summon the courage to escape the villa with Hoda for Cairo, he doesn’t get far, and then they fall asleep under a tree. (Cossery would have known Tawfik Hakim’s play Ahl Al-Kahf (Sleepers of the Cave), which was produced in 1933. The play focuses on the seven sleepers of Ephesus, a story in both the Christian and Muslim faiths, who took refuge in a cave to escape religious persecution. When they wake after a couple of centuries, they find the world has changed.)

Cossery had in mind the pasha landlords who found refuge in their villas from the punishing heat, while the enslaved peasants were working their fingers to the bone on the land. Although the sleepers of the cave were originally good, faithful people, Cossery couldn’t resist the attractive comparison with the feudal idlers. The awakening came after the publication of Cossery’s novel: when the Free Officers expelled King Farouq and confiscated much of the land and wealth of the elite in 1952. The novel was later adapted into a film, Idlers in the Fertile Valley, by the Greek director Nikos Papagiotopoulos, which won first prize at the Locarno Film Festival and second prize at the Chicago Film Festival in 1978.

Cossery had in mind the pasha landlords who found refuge in their villas from the punishing heat, while the enslaved peasants were working their fingers to the bone on the land.

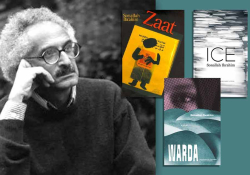

Mendiants et Orgueilleux (1955; Eng. Proud Beggars) was first translated in 1981 by Thomas Cushing and revised by Alyson Waters and published by New York Review Books in 2011. Gohar, a hashish addict, dreams he is drowning, but it is only the water leaking in from the flat of his neighbor, whose corpse is being washed. He yearns to go to Syria. His other friends are El-Kordi, a low-level bureaucrat who dreams of saving a prostitute with tuberculosis, and Yeghur, an Armenian poet and his hashish dealer. To earn a little extra money, Gohar keeps the accounts at the brothel but also writes letters for illiterate whores. Meanwhile, we are privy to the thoughts of Nour El-Dine, a frustrated police officer, who feels his job is absurd and dreams of sleeping with Samir, his handsome informant. In a momentary lapse of reason, Gohar convinces himself that the gold from the prostitute Arnab’s bracelet will pay for more hashish and his trip to Syria. Minutes after he has strangled her, he realizes the bracelet is fake. But since Gohar has surrendered to nihilism and pleasure, he is not bothered much by the death of sixteen-year-old Arnab, whose name means “rabbit” in Arabic. Since he doesn’t believe in anything, he doesn’t even have remorse for murdering the young girl. He is tormented by the quarrelling and lovemaking of his Amazonian neighbor, who is torturing her husband, an amputee beggar. The novel, full of idiosyncratic characters, seems to end abruptly, as if Cossery became weary of them.

La violence et la dérision (1964), translated into English as The Jokers by Anna Moschovakis, was published by New York Review Books in 2010. Of all Cossery’s novels that I have read, this is my favorite, which focuses on a practical joke on the governor of Alexandria, prepared by ex-revolutionaries recently released from jail, who scheme to beat the “powers that be” at their own game. Karim, the main character, is visited by a police officer who is flummoxed because he doesn’t know what he should write in his report since Karim is making kites for a living! Karim and Heykal, his disillusioned revolutionary comrade, decide to plaster the city with posters of the governor with praise so lavish, it is an obvious mockery. (Such iconography is a tool of dictators—I remember the giant posters of the Assad family on horseback that lined the hallways of Tishreen University when I taught there in the 1990s.) Nowhere does the author mention actual historical figures, like Gamal Abdel Nasser or others, but in 1964 the rose of the 1952 officers’ revolution was starting to lose its bloom. When one of the governor’s rivals sees the grand poster in the casino bathroom, he has a heart attack while urinating. Karim, who has just taped the poster on a stall, manages to escape undetected. But Taher, one of their revolutionary comrades, admonishes him for the prank and declares: “Fun is no way to fight.” Taher felt himself to be the “people’s proxy” and assassinates the governor, even though he has already been removed from his post. Both Proud Beggars (as Beggars and Noblemen, 1991) and The Jokers (2004) were adapted into films by the Egyptian filmmaker Asmaa El-Bakry.

Un complot de saltimbanques (1975) was translated by Alyson Waters and published by New Directions as A Splendid Conspiracy in 2010. When Teymour returns to Egypt from Paris, he prints out a fraudulent diploma to fool his father that he really was studying in Paris. He must evade his father’s proposal to work in a factory because he has no real training as an engineer! Instead, he joins up with his old friend, Medhat, who denigrates work and justifies his frequent visits to brothels with convoluted logic. Medhat introduces Teymour to Chawki, a lecherous aristocrat, who is keeping a very young mistress named Salma from a poor background. A naïve vet from the countryside has come to Cairo to collect his inheritance, but he gets sidetracked and falls for Salma. There is an atmosphere of paranoia in the city since “people are disappearing.” The police chief, Hillali is convinced that there must be a political conspiracy, although his informant “Rezq,” who is tailing the dissipated group, cannot find anything suspicious in their activities and believes his boss is living in a fantasy because he is lonely. On the other hand, Hillali is frustrated by his job and takes a fatherly interest in Rezq (which means “livelihood” in Arabic). Rezq wants to kill the corrupt Chawki, who humiliated his father in front of the neighborhood. But once Rezq has the chance, he realizes that Chawki is a pathetic figure, not worthy of his attention.

Les Couleurs de l’infamie (1999), also translated by Alyson Waters, was published as The Colors of Infamy by New Directions in 2011. The novel focuses on two pickpockets, Osama and Nimr, his mentor. Osama was penniless and so hungry he thought of killing himself. Suddenly, he is rescued in the street by Nimr, who teaches him the “tricks of the trade.” When Nimr (meaning “tiger” in Arabic) is released from prison, he is shocked to find that Osama is dressed like a dandy and sees himself as “too good” for his old working-class neighborhood. Osama believes he has hit the jackpot when he picks the pocket of a respectable-looking man in a fashionable area of Cairo and finds a letter containing evidence of government corruption. Suleyman, a developer, the brother of a minister, has evaded building codes, and this led to the collapse of a building and the deaths of fifty citizens. Nimr tries to convince Osama that, in fact, this will not be a scandal at all since the government ministers are just bigger thieves. When he fails to convince him, Nimr takes him to visit Karamallah, a journalist from an aristocratic background, who is on the run against the “powers that be.” Karamallah is now hiding in the City of the Dead necropolis yard, like many others who live on the margins: drug dealers, beggars, and homeless. But if the reader is expecting a dramatic end to this novel, they will be disappointed. Karamallah’s plan is to invite Suleyman to a café and humiliate him with scathing jokes.

In her afterword to A Splendid Conspiracy, translator Alyson Waters muses upon the word saltimbanques, which means “traveling circus performers,” “street entertainers,” or “acrobats.” The word is not widely used now in English, which is probably why the novel was entitled A Splendid Conspiracy, but perfectly describes the characters in Albert Cossery’s novels, and perhaps even Cossery himself, who was drawn to colorful characters from the street, largely ignored by “respectable” mainstream society. One only wishes that Cossery would have written more to amuse us—maybe he preferred quality to quantity. Or maybe was just too enchanted by the joie de vivre of the streets of Paris.

Cairo