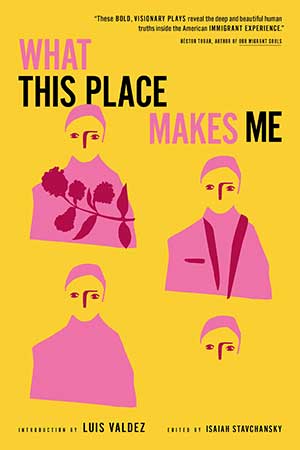

Why Plays Should Be Seen—and Read

The following is adapted from the editor’s note introducing What This Place Makes Me: Contemporary Plays on Immigration, now out from Restless Books.

Like many students in America, I didn’t grow up reading plays beyond Shakespeare and Arthur Miller. I had three actor grandparents, two of whom were active in the United States, and one in Mexico, so I saw quite a bit of theater as a child. My first memory of watching a theater performance was at about nine years old, when I went to my grandmother’s performance of The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler, a celebrated series of monologues about sex, menstruation, and reproduction, among other subjects. Even with that unforgettable early exposure, I remained unfamiliar with playwriting.

Like many students in America, I didn’t grow up reading plays beyond Shakespeare and Arthur Miller. I had three actor grandparents, two of whom were active in the United States, and one in Mexico, so I saw quite a bit of theater as a child. My first memory of watching a theater performance was at about nine years old, when I went to my grandmother’s performance of The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler, a celebrated series of monologues about sex, menstruation, and reproduction, among other subjects. Even with that unforgettable early exposure, I remained unfamiliar with playwriting.

I spent all of 2016 in the UK, seeing plays and studying the medium as literature. Amid the exhausting political landscape of that year, something clicked and I decided that I wanted to spend my life in the theater. Theater is the place where I could feel most engaged and inspired. Theater examines the way societies function and how that impacts the individual. In a world dominated by short narratives on social media that disappear as quickly as you’ve seen them, the stage allows for an unavoidably dynamic storytelling. As an audience member, I couldn’t hide from the actors in front of me or from my fellow theatergoers. I was part of a singular communal experience.

After that, I wanted to explore American plays that reflected my multicultural upbringing. I had no idea how challenging it would be to find them. Upon my return home to Amherst, Massachusetts, I visited my public library and found plays by Shakespeare, Chekhov, Albee, and Shepard, but almost nothing from the twenty-first century. At my local independent bookstore, I stumbled upon the invaluable Norton Anthology of Drama. Although it provided a broad perspective on Western drama, its most recent play was The American Play by Suzan-Lori Parks from 1994.

As a result, I had to create my own reading list of contemporary plays. I decided I would read every Pulitzer Prize–winning play to date. The prize, which had been continuously awarded for nearly a century at that point, prided itself on championing a “distinguished play by an American author . . . dealing with American life.” Immigration is fundamental to my understanding of American life. As I read through many of the most esteemed plays of the last century, I hoped to encounter the contemporary narratives I craved. I discovered that much of the conversation only lightly touched on immigration. I encountered comic plays I’d never heard of, such as the 1944 production of Mary Chase’s Harvey, plays that I only recognized as movies, like Jason Miller’s 1972 production That Championship Season, and plays whose brilliance left me astonished, such as Robert Schenkkan’s 1991 production The Kentucky Cycle. While these works are innovative and depict aspects of American life, they don’t fully encompass the multitudes of the America that I knew. I couldn’t help but feel disappointed that there were few plays by Latinx writers, few plays by or about immigrants, and few plays addressing cross-cultural identities.

Theater exploring the immigrant experience—love, despair, triumph, failure, and perseverance—has always existed. But of the nearly one hundred Pulitzer winners, there were only a few that touched on these themes directly.

Theater exploring the immigrant experience—love, despair, triumph, failure, and perseverance—has always existed.

In the honorable mentions for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, I found a treasure trove of immigrant writers, such as Stephen Karam, Rajiv Joseph, and Kristoffer Diaz. I could only assume that, like most immigrant contributions in America, their brilliance has gone largely uncelebrated, often because of the color of their skin, the cadence of their English, or the language in which they write.

And then I encountered another equally significant issue: even if I could identify the playwrights I wanted to read, I couldn’t access their plays unless I bought copies online.

The root of the problem rests in how plays are published in the US. The extent of reader-focused theatrical publishing in America is dwarfed by that of other countries. Most plays are made available largely in actors’ editions, typically recognizable as Samuel French paper booklets. These prints are designed for practical use, to be carried during rehearsals, marked up, and so on. They are tailored for theater artists. The majority of these books never find their way onto the shelves of local bookstores.

*

In my now-local bookstore in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, home to a diverse community of theater artists, most of the plays I can find premiered before the turn of the century. The store manager explained to me that they rely on an advisor who suggests books that are likely to sell, and stock their shelves accordingly. Unless plays are specifically requested by customers, they don’t appear in the bookstore.

Public libraries acquire books similarly. Book publishers submit their titles to various publications that review and recommend them. Librarians read those publications and decide which books to include in their collections. Most publishers of plays do not submit their books to these reviewers, which means that plays aren’t on the average librarian’s radar.

The most recent anthology of contemporary American theater is the second volume of The Oberon Anthology of Contemporary American Theater, published in 2018. I learned that many library systems do not carry even a single copy of it. The Los Angeles Public Library, one of the largest public libraries in America, had two copies of the first volume, published in 2012, but none of the second. How is it possible that some of our largest public libraries lack a single copy of the most recent anthology of contemporary English-language plays? As a consequence, each year, booksellers allocate less and less shelf space to plays. The American publishing industry views publishing theater as unprofitable. Without readership, plays don’t end up on library shelves either. With the concentration of professional theater in urban settings (not to mention soaring ticket prices), books can be a powerful tool to inspire interest in theater among the general readership. Books offer a more affordable and accessible medium. In collaboration with public libraries across the nation, they could even be made available for free.

A play serves as an artifact that provides insight into how a storyteller crafts a narrative.

The act of reading plays offers a distinct opportunity to peer into the minds of playwrights. While any performance is an interpretation of the written word, a play serves as an artifact that provides insight into how a storyteller crafts a narrative. To read a play is to partake in a shared experience of the text. American playwrights from decades past are already included in high school curricula. Playwrights like Arthur Miller, Sophie Treadwell, and Lorraine Hansberry reside on our library shelves alongside authors like Jhumpa Lahiri, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. We include them because we believe these plays should not only be performed, but read. If we don’t make contemporary plays accessible to readers, tomorrow’s immigrant children outside our major cities may not have the chance to discover our thriving theatrical tradition. It is high time our contemporary immigrant playwrights be read as literature.

New York City

Editorial note: Adapted from What This Place Makes Me: Contemporary Plays on Immigration (Restless Books, 2025). Editor’s note copyright © 2025 by Isaiah Stavchansky. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.