The Literary Interventions of Chibueze Darlington Anuonye

Nigerian writer, editor, and scholar Chibueze Darlington Anuonye’s pioneering essay on contemporary Nigerian poetry, “Facebook Writers: The Emergence of a New Generation of Nigerian Writers,” was recently translated into Arabic, French, German and Spanish by the Munich-based literary journal Literatur Review. A rare accomplishment in African literary scholarship, these translations are expanding the readership of Nigerian literature beyond the English-speaking world.

Since the second decade of the twenty-first century, Nigerian poetry has been dominated by young writers who deploy social media as a publishing platform. Perhaps for the unconventional themes of their writing and their digital approach to publishing in a print-oriented literary establishment, these poets were for some years underrepresented in Nigeria’s literary academy. In December 2022, on the launch of the forty-ninth issue of the Muse Journal at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Anuonye strongly advocated for the recognition of these writers as the “fourth generation of Nigerian poets” in his keynote lecture. This lecture was later published as a critical essay in May 2024. The first indication of the status of the essay as a work of pathfinding scholarship of international significance is that it was published in Research in African Literatures, “the premier journal of African literary studies worldwide” and possibly the most distinguished in the field. Anuonye was twenty-nine at the time his essay was published; he is certainly one of the youngest scholars to be featured in Research in African Literatures since its establishment in 1970.

In “Facebook Writers,” Anuonye explains that the group of young poets he writes about “has made strategic interventions in Nigerian writing by establishing social media literature with Facebook as their foremost publishing platform; mainstreaming digital publishing; influencing a new tradition of queer, self-conscious, and subversive poetry; and earning significant literary prizes and commendations throughout the world.” Anuonye rejects the notion that unlike poems published in literary magazines and journals, poems published on Facebook are wont to lack quality, having not passed through any editorial scrutiny. He argues that “this new generation of poets does not only publish their works on Facebook, they also provide mentorship and support to one another, ensuring that their poetry is of great quality.” The peer review and editorial feedback happen in real time in the comment sections of these posts, and we have witnessed cases in which a poet uses the “edit” option to implement some feedback.

Anuonye goes further in this essay to read selected Facebook poems. His analysis demonstrates the literary quality of the poems and emphasizes that while it may be true that some poets bring their “bad” works to Facebook and take their “good” ones to journals and magazines, these poets produce quality poems on Facebook. Academic engagements may have led some notable names from this group, many of whom now teach in universities abroad, like Romeo Oriogun or Sadiq Dzukogi, to no longer actively write poetry on Facebook, but others like Rasaq Malik Gbolahan are gifts that never stop giving. “Facebook Writers” provides the intellectual foundation for the study of emerging Nigerian poetry, which comprises the works of more than a hundred poets.

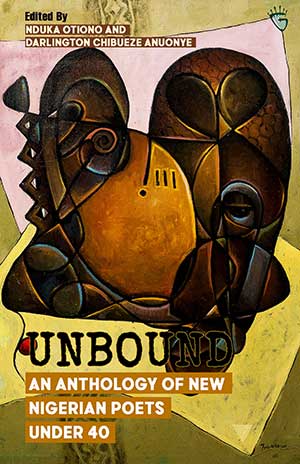

Anuonye not only theorizes the works of fourth-generation Nigerian poets, but he has also curated and edited them, alongside Nduka Otiono, in Unbound: An Anthology of New Nigerian Poets under 40, forthcoming from Griots Lounge Canada and Narrative Landscape Nigeria in June 2025. In his introduction to the anthology, Anuonye offers the following justification for his “intellectual and emotional investment” in these writers’ poetry: “These new poets emerged on the Nigerian literary scene with a boisterous passion for storytelling, a complete allegiance to the imagination, a transforming awareness of the self, and an ethical disavowal of essentialist assumptions about community and culture.” Beyond its focus on the anthology, Anuonye’s introduction is also a response to the debate on the identity and purpose of the poetry of emerging Nigerian writers, many of whom are anthologized in Unbound. Engaging individually and collectively the critics driving the conversations about the “death” of Nigerian poetry, Anuonye encourages critics not to miss the essence of the poets’ works. “The idea of purposeful reading,” he writes, “is lost when the critic neglects the social and political contexts from which writers and their texts emerge or are in conversation with.” Here, Anuonye reminds us that literature, just as his countryman and Marxist scholar Chidi Amuta says in Theory of African Literature, “is a product of people in society and a producer and reproducer of the cognitions and values of society.”

Anuonye not only theorizes the works of fourth-generation Nigerian poets, but he has also curated and edited them, alongside Nduka Otiono, in Unbound: An Anthology of New Nigerian Poets under 40, forthcoming from Griots Lounge Canada and Narrative Landscape Nigeria in June 2025. In his introduction to the anthology, Anuonye offers the following justification for his “intellectual and emotional investment” in these writers’ poetry: “These new poets emerged on the Nigerian literary scene with a boisterous passion for storytelling, a complete allegiance to the imagination, a transforming awareness of the self, and an ethical disavowal of essentialist assumptions about community and culture.” Beyond its focus on the anthology, Anuonye’s introduction is also a response to the debate on the identity and purpose of the poetry of emerging Nigerian writers, many of whom are anthologized in Unbound. Engaging individually and collectively the critics driving the conversations about the “death” of Nigerian poetry, Anuonye encourages critics not to miss the essence of the poets’ works. “The idea of purposeful reading,” he writes, “is lost when the critic neglects the social and political contexts from which writers and their texts emerge or are in conversation with.” Here, Anuonye reminds us that literature, just as his countryman and Marxist scholar Chidi Amuta says in Theory of African Literature, “is a product of people in society and a producer and reproducer of the cognitions and values of society.”

Engaging individually and collectively the critics driving the conversations about the “death” of Nigerian poetry, Anuonye encourages critics not to miss the essence of the poets’ works.

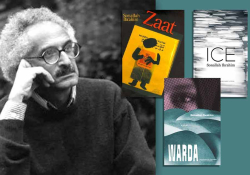

The cultural significance of Anuonye’s scholarship shines through his ability to illuminate the literary values of the works of writers at the canonical margins of African and global literatures. His essays on the novels of Tanzanian writer Abdulrazak Gurnah are exceptional in this regard. On October 7, 2021, Mats Malm, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, announced Gurnah as the winner of the year’s Nobel Prize in Literature, “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.” This was a momentous event, not only because every Nobel Prize announcement reverberates around the world, but also because Gurnah’s work had not yet been discovered by a global audience. So, whether it was in England where Gurnah lived most of his adult life or in Africa from where he came, the “obscurity” claim tended to undermine his deservedness of the award. Anuonye, then studying for a master’s in literature at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, joined the conversation around Gurnah’s Nobel with the conviction that the “obscurity” debate was a distraction, maybe even a lazy and unliterary way of evaluating Gurnah’s award. What mattered to Anuonye was the need to evaluate the literary merits of Gurnah’s novels. He may have taken his cue from Ellen Mattson, who sits on the Nobel committee of the Swedish Academy. For Mattson, “literary merit” was the only consideration for awarding Gurnah the prize. Anuonye, therefore, chose to research, for his thesis, “The Literary Merits of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Nobel Prize,” probably the first book-length critical assessment of Gurnah’s writing within the context of the Nobel canonization.

Portions of Anuonye’s thesis, focusing on the humanistic qualities of Gurnah’s novels, have been published in The Muse and ANA Review. For Anuonye, Gurnah is “an artist of immense gift and generosity.” In “The Empathetic Quality of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Paradise,” he observes that Paradise, like many of Gurnah’s novels, “expresses an unusual devotion to the lives of ordinary people, whose roles in the historical processes can be easily erased from social memory.” Anuonye’s claim is that Gurnah refuses to promote stereotypes or strip his characters of their humanity, no matter how imperfect they are. Rather, Gurnah empathizes with them, which means he tries to understand the why to whatever crimes they may have committed, the factors that accumulated unnoticed until finally triggered and malevolently released. Consolidating the decision of the Nobel committee, Anuonye concludes that “by delving into the historical tragedy and trauma behind these characters’ crimes, Gurnah illustrates that we are all responsible for one another in a chain that can create or destroy. This is a great lesson in humility and humanity.”

Anuonye expatiates his thesis that Gurnah’s life and writing are dedicated to the promotion of humanistic ideals in “Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Deep Humanism,” forthcoming from Transition magazine. “Since he arrived in England in 1968 as a refugee,” Anuonye writes in this essay, “Gurnah has devoted himself to the art of fiction as a means of reflecting on the conditions that made his departure inevitable. In novel after novel, he imagines the ways Africans confront the trauma of colonial subjecthood and the loneliness of exile by creating small, powerless, flawed but ultimately human characters negotiating their freedom in a hostile world.” Taking Pilgrims Way as an example, Anuonye notes that “both the European and African characters in the novel are depicted as victims of the inner workings of society, culture and history.” But the oppressed in Gurnah’s novels, Anuonye cautions, are not just victims devoid of agency. Memory of Departure, he explains, “demonstrates the astonishing possibility of freedom for the oppressed.” For the oppressed to be free, for them to be able to demand freedom, it is imperative that the factors keeping them in subjugation are identified and named. As Anuonye shows, Gurnah names the oppression he writes about, even if the stories are complicated.

Anuonye has a gift for unraveling complexities. Reading Gurnah’s novels, he is aware that “the disinheritance of African women continues today by the sinister collaboration of the colonial culture of female subjectivity and the traditional African system of patriarchal hegemony.” Also, he discerns that for the poor African immigrants in the novels, poverty “is hardly the only misfortune” they experience. There is also the sociopolitical and cultural issue of powerlessness. “Powerlessness is perhaps their immediate and more menacing lot,” Anuonye asserts. Yet he establishes that “Gurnah does not ignore small lives, no matter how conquered they may seem.”

Anuonye’s reading of Gurnah’s novels is consistent with his idea that African literature is invested in the ideal of human freedom.

Anuonye’s reading of Gurnah’s novels is consistent with his idea that African literature is invested in the ideal of human freedom. Reflecting on his own work in the field, Anuonye remarks: “Whether I am writing, critiquing or teaching an essay, or creating a conversation, I consider myself performing the function of cultural regeneration, the kind that refuses the erasure of marginalized peoples around the world.” In his roundtable essay “African Literature of Ideas and the Prospect of Collective Individualism,” Anuonye expounds this notion when he writes that “African literature does not just contain ideas and philosophies; it is, first and foremost, a product of cultural exigency and an expression of the individual writer’s agentic self.”

Anuonye’s reading of Gurnah’s novels is consistent with his idea that African literature is invested in the ideal of human freedom. Reflecting on his own work in the field, Anuonye remarks: “Whether I am writing, critiquing or teaching an essay, or creating a conversation, I consider myself performing the function of cultural regeneration, the kind that refuses the erasure of marginalized peoples around the world.” In his roundtable essay “African Literature of Ideas and the Prospect of Collective Individualism,” Anuonye expounds this notion when he writes that “African literature does not just contain ideas and philosophies; it is, first and foremost, a product of cultural exigency and an expression of the individual writer’s agentic self.”

This belief informs his autobiographical reading of Ukamaka Olisakwe’s Ogadinma, a novel that is steadily becoming a feminist classic. In “The Autobiographical and Feminist Background of Ukamaka Olisakwe’s Ogadinma,” Anuonye illustrates how Olisakwe’s personal experiences inform the strength and agency she bequeaths her character Ogadinma. Anuonye’s interest in the lives of writers explains his view in the essay that “African writers are thinkers, just as they are storytellers; their ideas and philosophies are so deftly embedded in their works that it is almost impossible not to see how central their role as thinkers and how varied their thoughts as individuals are to their creative endeavour.” Essentially, Anuonye considers Olisakwe’s feminist ideals “so deftly embedded” in Ogadinma that “Ogadinma’s confusion is perhaps Olisakwe’s portrayal of the female condition in a patriarchal society as a life of inevitable mental struggle.” But there is the possibility of redemption. “When Ogadinma reads” Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood “in her moment of self-love, what emerges,” Anuonye reveals, “is the image of Olisakwe bequeathing her most cherished book to her character, with the hope that Ogadinma experiences the freedom of self-expression and the courage of self-assertion that Emecheta offered her.”

Anuonye’s work is widening the cultural and philosophical orientations of African literature. He has shown us the possibility of having, for example, an Ogadinma who not only reacts to patriarchy within the scripts of documented feminism but dares to shape the idea of female emancipation by confronting the culture of patriarchy. He has also foregrounded “the revolutionary potentials of the intersections of digital technology, literature and activism” in contemporary Nigerian poetry and celebrated the philosophical properties of oral cultures across Africa, in his reading of early modern African novels. It is in this manner that Anuonye’s literary interventions advance African literature, drawing attention to literature as it concerns the merits of its form and style as well as the relevance of its content, while also making provisions for improvements, both in the writer as a producer and the reader as an active consumer. Whether he is engaging the novelist or the poet, Anuonye’s literary interventions are aimed at serving the underrepresented: his generation of African poets, writers writing from the margins, writers writing for the marginalized.

Winnipeg

Editorial note: As of July 2025, Anuonye is the newest member of the WLT editorial board.