Kwame Dawes: Profile of an Editor

Kwame Dawes, who was until recently the Glenna Luschei Editor-in-Chief of Prairie Schooner, served the magazine for thirteen years. He brought to that role an admirable interest in international cultures, which helped place American writing in conversation with literature from around the world, especially from Africa and the Caribbean, where he has ancestral roots.

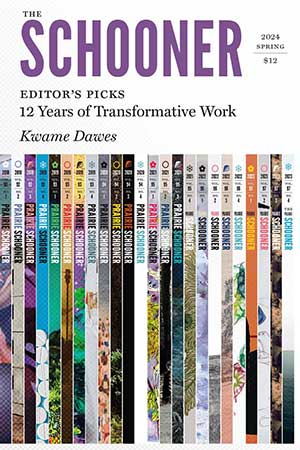

Once he assumed the editorship in 2011, Dawes established an advisory board whose members would help direct the magazine’s vision and consolidate its public image and economic capital. Dawes announced the literary ambition of his tenure in his first issue. “Prairie Schooner founders,” he wrote, “were savvy to branding and corn, farms, prairie, and of course prairie schooners were the branding icons they could not get enough of. . . . I want to reassure our ultra-modern urbanities that I am not returning to the farm lock, stock, and barrel, but . . . even if my columns will not be shot through with metaphors of the prairie, the fundamental impulse to practicality and efficiency will, I hope, guide what I offer you in these columns.”

Once he assumed the editorship in 2011, Dawes established an advisory board whose members would help direct the magazine’s vision and consolidate its public image and economic capital. Dawes announced the literary ambition of his tenure in his first issue. “Prairie Schooner founders,” he wrote, “were savvy to branding and corn, farms, prairie, and of course prairie schooners were the branding icons they could not get enough of. . . . I want to reassure our ultra-modern urbanities that I am not returning to the farm lock, stock, and barrel, but . . . even if my columns will not be shot through with metaphors of the prairie, the fundamental impulse to practicality and efficiency will, I hope, guide what I offer you in these columns.”

The fundamental concern at the time was how an American magazine, almost alienated from the intellectual culture of the outside world, would survive in the postmodern present and future. Dawes relied on his capacity for global literary networking to ensure that Prairie Schooner attained international visibility. For this feat, he received the PEN/Nora Magid Award for Magazine Editing in 2021, a prize that “honors a magazine editor whose high literary standards and taste have, throughout their career, contributed significantly to the excellence of the publication they edit.”

As a writer and creative writing professor who reads both for pleasure and out of commitment, Dawes is a liberally educated and competent editor. To mark his fifth year at Prairie Schooner, Dawes was interviewed by Frontier Poetry about his experience editing the magazine. When he was asked for book recommendations for writers eager to master the art of poetry, Dawes replied: “Books on craft are helpful, but reading poetry, work from around the world, from all ages, from all periods, that is what allows us to read with confidence those ‘authorities.’ And so when it comes to books I find myself recommending often, two come to mind: Kamau Brathwaite’s The Arrivants, and Ntosake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf.”

In addition to these texts, Dawes considers Richard Hugo’s Triggering Town an essential collection for American writers, because “it is a fine contradictory book full of splendid and not so splendid ideas, but blessed with the attitude of a practicing poet who is skeptical of his own advice.” And although he thinks “Pound’s ABC of Reading . . . is so annoying,” Dawes recommends the book because it is “so rich with stuff we must all disagree with, and so full of itself that it forces us to develop our own intelligence of what is valuable in poetry.” Brief as this list is, it reveals the global range of his reading: from America to Britain to the Caribbean, every culture and literature has a place in Dawes’s capacious mind.

From America to Britain to the Caribbean, every culture and literature has a place in Dawes’s capacious mind.

Beyond his cultivated literary taste, Dawes is also, in the words of the PEN award judges Patrick Cottrell, Carmen Giménez Smith, and John Jeremiah Sullivan, “a bold and visionary editor.” His advocacy for and representation of international writers in the pages of Prairie Schooner is enduring proof of his boldness and vision.

Dawes’s artistic inclination is complex—poet, actor, editor, critic, musician—and so is his ancestry. He was born in Ghana in 1962 to a Ghanaian mother and Jamaican father. Neville August Dawes, his father, also a distinguished poet, literary critic, and teacher, was born in Nigeria in 1926, when his own father was a railway worker for the British colonial government.

Both Dawes’s maternal and paternal families provided him with much literary and cultural inspiration. The pioneering modern African poet Kofi Awoonor was, in fact, his maternal uncle and literary mentor. In an interview with Tryphena Yeboah, Dawes offers an intimate account of his formative years, highlighting the role his background played in his creative becoming: “My mother completed training as an artist in Ghana, and continued primarily as a sculptor for years. . . . As a child, I found myself serving as her apprentice especially as she sculpted. . . . When we moved to Jamaica, my father was the director of the Institute of Jamaica, which was the cultural institution of the island. This ensured that we would find ourselves waiting around at art exhibitions and musical performances, attending major theatrical productions, and of course, watching the artistic minded entertain themselves. We were eavesdropping on all of this, but it certainly normalized the artistic pursuit in my mind.”

So, when the University of Nebraska hired Dawes to edit Prairie Schooner, they created an opportunity for him to express the grandeur of his hyphenated artistic, cultural, and geographical heritage and to elevate the magazine beyond its national boundaries. Under Dawes’s careful yet boundlessly creative stewardship, Prairie Schooner gracefully faced the world’s beauty and ugliness with courage, gently spoke to the world, fiercely represented what is best about humanity in the world, and openly denounced what is worst. Dawes performed the necessary task of civilization.

Since Dawes’s first issue in the winter of 2012, Prairie Schooner has maintained considerable diversity in its representation of writers from cultures and nationalities outside the United States. In this inaugural edition, Dawes featured Native American writings as an important body of work that requires greater attention than it had received in the past. These works were guest-edited by the Native American writer and filmmaker Sherman Alexie, whose 2007 young adult novel, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, won the US National Books Award for Young People’s Literature. dg okpik’s poem in the issue, “Days of Next Yesterday,” gives voice and agency to Native American, female, and human experiences.

All the world is the new, encompassing prairie of our widening imagination.

In his last issue at Prairie Schooner, Dawes pursues the project of canonicity by curating some of the finest works published during his tenure as editor. He concludes his tenure by placing the future of the magazine in the hands of succeeding editors when he announces his hope that the title The Schooner, rather than Prairie Schooner, would endure with the magazine. All the world is the new, encompassing prairie of our widening imagination. This is what Dawes wants Prairie Schooner’s future editors to consider. The prestige of a magazine is often linked to the credentials of its editor. In this regard, Dawes’s hyphenated ancestry, his global literary connections, and his stature as an accomplished writer and public intellectual have been of immense benefit to Prairie Schooner. We should remember this legacy with gratitude.

University of Nebraska–Lincoln