Audiobooks and Charles Dickens’s Victorian Practice of Reading Aloud

According to Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier, reading aloud was a common practice in the ancient world, the Middle Ages, and as late as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (A History of Reading in the West). Readers were “listeners attentive to a reading voice,” and “the text [was] addressed to the ear as much as to the eye.” The significance of reading aloud continued well into the nineteenth century. Today’s audiobooks can be considered a contemporary version of the practice.

However, while the twentieth- and twentieth-first-century trend for individuals to listen to audiobooks while jogging, commuting, or working out at the gym retains some characteristics of traditional reading aloud—such as “listeners attentive to a reading voice” and the ear being the focal point of attention—it is a far more solitary activity. The sense of community fostered by collectively listening to a text is less tangible and more imaginary.

The sense of community fostered by collectively listening to a text is less tangible and more imaginary.

Using Charles Dickens’s nineteenth century as a point of departure, it would be useful to look at the familial and social uses of reading aloud in a previous era, prompting us to reflect on the functional change of the practice. Dickens habitually read his work to a domestic audience or friends. In his later years he also read to a broader public crowd, first for charity purposes, then as a second profession. Episodes of reading aloud also abound in Dickens’s own literary works. More importantly, he took into consideration the Victorian practice when composing his prose, so much so that his writing is meant to be heard, not only read on the page.

Performing a literary text orally in a Victorian family is well documented. Apart from promoting a congenial family relationship, reading aloud was also a means of protecting young people, especially adolescent girls, from the danger of solitary reading. Reading aloud was a tool for parental guidance or supervision. Sometimes parents read books aloud to children and tested them on the content afterward; this served as the basis of home education. By means of reading aloud, parents could also introduce literature and the Bible to their children, and as such the practice conflated leisure and more serious purposes such as aesthetic and religious cultivation in youngsters.

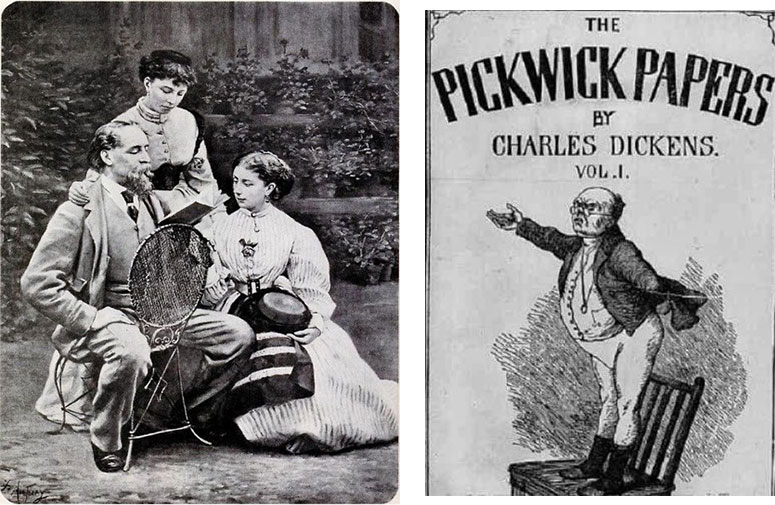

Within the family, it was commonplace for the father to read aloud. Dickens read to his children: one of his surviving and oft-reprinted photographs features him posing on a chair, reading to his two daughters, Mamie and Katey, in the garden of Gad’s Hill. Though the reading activity was framed outside, it was still in a cozy setting, which contrasts markedly with the public readings Dickens gave on stage in front of large crowds. According to Philip Collins, “In many genteel houses . . . papa would read the instalments of the successive novels to the assembled family.”[1] The “papa” figure seems to possess a lordly aura, reading to an attentive domestic audience. Although not mentioned as frequently, the Victorian mother was also keen to read to the family.

Reading aloud in the nineteenth century was as much a class phenomenon as a family affair. Richard Altick notes that “the audience for the literature which continues to be read today was concentrated . . . in the middle class” (Victorian People and Ideas). This comment points to a widespread conviction that Victorian readership, for most contributors to magazines, professional novelists, and critics of the period, primarily meant a middle-class readership. Those who fell outside this group—for example, people from lower social orders and the relatively uneducated—tended to be overlooked by Victorian publishers.

Despite this general conviction, Dickens, with his publishers Chapman and Hall, managed to distribute literary reading materials to people from different social strata by reducing the price of novels through serialization. This was also made possible with the technological and mechanical advances in printing, entrepreneurial capitalism, and the spread of railway networks at the time. Jerry Don Vann gives sole credit to Pickwick Papers for broadening the Victorian readership: it “greatly enlarged the reading audience, who . . . could not manage the price of a published volume but could afford the monthly instalments” (Victorian Novels in Serial).

Pickwick Papers, first appearing in April 1836 and ending in November 1837, overlapped two monarchies and was published in twenty parts in nineteen monthly installments. All of Dickens’s succeeding novels were serialized either in a weekly or, more often, a monthly format. Thus, the reader could purchase a novel that was longer than the three-volume duodecimo for two-thirds of the normal price. The lower pricing encouraged members of the working classes to read fiction; Wilkie Collins, Dickens’s contemporary, termed these readers “the unknown public.”[2]

It seems significant, then, that Dickens took advantage of serialized forms of publication, otherwise the “unknown” readership would remain deprived of reading experience altogether. Serialization and the lower price of reading materials admitted a larger readership. Some of the new readers would have assembled and read a shared copy of the most recent issue in open spaces. A working-class home was in many ways not convenient for reading: it was crowded, it was bedlam, there were too many distractions, the lighting was bad, and the home was also often half a workhouse. As a result, the Victorians from the non-middle classes were inclined to find relaxation outside the home such as in parks and squares, which were ideal places for the public to go while away their limited leisure time. These contexts determined the reading environment among the non-middle classes.

Since the literacy level of this section of the population was still low before school attendance was made compulsory in 1870 by the Education Act, a considerable number of people from lower classes would listen to recitals of texts. Dickens’s readers, who were from such social backgrounds, might have heard Dickens in this manner. Jeremy Hawthorn says that “there have been cases of illiterate people gathering to hear novels read—part of Dickens’s audience was of this sort” (Studying the Novel).

Several biographers of Dickens also draw attention to the fact that it was typical for his texts to be read aloud in Victorian England, and thus illiteracy was not an obstacle for reading Dickens. Philip Collins, for example, writes that “even some of the illiterate were familiar with [Dickens] through theatrical versions or by attending penny readings,” while Edgar Johnson also reports that there was an elderly charwoman who could not read but “attended every month a tea held by subscription at a snuff shop, where the landlord read [Dickens] aloud.”[3]

* * *

Dickens’s works were read aloud by different social groups. The practice as such transcended the “private” and the “public” spheres. Originally a home-bound activity, the act of reading was beginning to expand from the boundaries of the comfortable refuge of a middle-class home and into the more inclusive public realms of work and leisure. Reading was no longer a chiefly closeted form of entertainment practiced by the middle class at home. Moreover, reading aloud, in particular public reading, to some extent blurred the distinctions between classes. The Victorian middle class defined its identity through differences with other classes. Dickens’s mode of publication and his popularity among readers from the non-middle classes contributed to the creation of a new class of readers who read through listening.

Reading was no longer a chiefly closeted form of entertainment practiced by the middle class at home.

Two types of readers were involved in the reading scenarios mentioned above: the reader who read aloud and a different kind of reader, one who, though illiterate, was able to read with the ears rather than the eyes. These different readers of Dickens were not reading solitarily and “jealously,” to use Walter Benjamin’s term. Instead, they often enjoyed a more communal experience, an experience that is generally lacking in today’s world.

Hong Kong Baptist University

Footnotes

[1] Philip Collins, ed., “Contemporary Review” in Dickens: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971), 6.

[2] Richard Altick, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900, 2nd ed. (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1998), 5.

[3] Collins, “Contemporary Review,” 16; Edgar Johnson, Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph (New York: Penguin, 1986), 327.