The Stranger and Her Escapes: A Review of Swallowing Mercury, by Wioletta Greg

It is not easy to be a poet; certainly not when you live away from the language in which you feel, see, and analyze everything around you. Emigration isn’t easy for poets, who live to seize the world in short verses. It is quite different with fiction; prose has its own rules, rights for reminiscences and description. Perhaps this is why Wioletta Greg decided to write prose even though for years she has been writing intriguing poetry, both serious and ironic, and deeply penetrating the laws of reality?

It is not easy to be a poet; certainly not when you live away from the language in which you feel, see, and analyze everything around you. Emigration isn’t easy for poets, who live to seize the world in short verses. It is quite different with fiction; prose has its own rules, rights for reminiscences and description. Perhaps this is why Wioletta Greg decided to write prose even though for years she has been writing intriguing poetry, both serious and ironic, and deeply penetrating the laws of reality?

When asked about it, Greg said, “Sometimes I think that I write less poetry because of losing the connection with the Polish language. When you pass through so many places in your life, you become split between them. A need of stories awakens within you, like Odysseus. It is almost like the desire to record everything as a means of defense against your loss.”

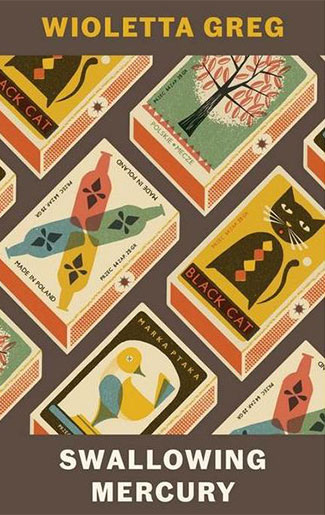

As a prose writer, Greg first published, in Polish, the autobiographical Notatnik z wyspy (2012; Notebook from an island), her notes from the Isle of Wight, where she lived after leaving Poland. Then, in 2014, she published Guguły (Unripe fruits), a powerful tale of a grown-up woman who takes readers for a trip into the psyche of a little girl in a small village in the 1980s, a girl whom Greg resembles.Newly released in translation as Swallowing Mercury (2017)—published by Portobello Books and skillfully rendered by Eliza Marciniak—Guguły stands a good chance of winning the hearts of many English-language readers.

These recollections, idyllic on the surface, exhibit, in fact, cruel rules of poverty, survival, and feudal loyalty to tradition.

Swallowing Mercury is a set of short recollections about being a child in a tiny place in southern Poland (which might be any other little European village). These recollections, idyllic on the surface, exhibit, in fact, cruel rules of poverty, survival, and feudal loyalty to tradition. You know how it is to be stunned by a child’s naïve yet accurate accounts of death, illness, or suffering, stating facts without searching for meaning or any explanation, just describing the manifestations of things and time? This is how Wioletta Greg sketches Hektary, the village from Swallowing Mercury: with a sharp interest in details, the perspective of an insider, and yet someone constantly astonished by the mechanisms vital and mortal, visible and secret aspects of every day. Time is measured by events, and people are pictured through their activity: “A few more months have passed. Ducklings hatched in the hallway. . . . My grandfather started to plane down . . . rockers for my rocking horse . . . a thin man with curly hair and a little moustache came into our house. After he saw me, he cried for a whole day, and he calmed down only when Poland started playing in the World Cup.” Even the humor or irony of this example, associating man’s sensitivity with soccer, is natural, childlike, and elusive.

The whole story may feel like the mythologizing of a childhood, but the narrator is fully aware of the roughness of a small place and how violent it can be toward any individual, let alone a vulnerable child. This is why Swallowing Mercury, by creating a pseudonostalgic narrative with melancholic threads, exhibits the reasons for escaping, emigrating, or simply running away. Somehow, under the skin of the plot, we see the desire to abandon a place. When, at the end of the book (warning: plot spoiler), the main character gives up on the planned escape and goes back to her village, we know: it is just a matter of time, but not yet.

Playing with Fiction and Reality

Mixing reality and fiction, gluing together real and fictive Wiolas, we know that the real Wioletta runs away soon: first to Częstochowa, for studies, then to the Isle of Wight, and, now, to London. And these escapes gave the author the necessary distance to see her small town and its mechanisms in clearer focus: she looks bravely into the life of a family that easily may have been her own and describes the gloomy lives of people who could be her mother, father, and grandparents in the most compassionate yet honest way: describing how their provincial lives were intertwined with wars and ideologies, poverty and the need to survive, each in their own way. We have women struggling to survive when men are arrested in the turmoil of communism seen as a normal daily routine. We have a theme of disappeared Jews who revisit their once-abandoned homes seen as a curious episode of one afternoon (a similar picture appears, for example, in Olga Tokarczuk’s House of the Day, House of the Night).

Yet Greg’s characters are far from being stiff icons of the time. The writer gives a lot of personality to each of the protagonists. For example, her father, perhaps the most significant person for little Wiola, is the least rooted in reality; an artist who fills the emptiness of his life by stuffing animals, creating afterlives (reminiscent of Bruno Schulz’s mannequins). The clear, simple sentences of a child’s perspective describing each of the characters highlight even more the absurdity of reality and how it intertwines with religion and politics.

The Foreigner

Three years ago, in 2014, Greg published Finite Formulae and the Theories of Chance (Arc Publications). This was the second English-language collection of her poems, after Smena’s Memory (Off_Press, 2011). Finite was the first publication in which Wioletta Grzegorzewska changed her surname to Greg. This is a gesture of a foreigner (cudzoziemka), who—recognizing the peculiarity of her surname—tries to reshape it according to the phonetics of the new land. But surely for many of us it is so much easier to remember Greg than Grzegorzewska. And perhaps it is easier to talk about the poetry when we have no problem pronouncing the author’s name. And there is a lot to talk about.

Wioletta Greg’s poetry is exceptional; we find here enigmatic summaries of various family stories, poetic notes on events of the twentieth century, folklore, emigration notes, aesthetics of bodily experience, and an amazing sensitivity toward light, colors, and taste. It contains a constant notion of escaping, migration, like in the poem “Missing,” in which the first escape appears to be into the fruit tree:

Look for me in the attic, beneath the tarp

and the lily leaves, at the bottom of the quarry.

I am perched on a cherry tree, swallowing unripened fruit,

the tree whispering: I will hand you over to the starlings.

Greg’s poetry, just like Greg’s fiction, describes the inside of fruit, the surface of a tree’s trunk. It recognizes the stomach pain and the pain of existence in small places, where the contingency of events is somehow painfully visible, like the inevitability of death, yet delightfully seductive.