A Rush of Indian Stories: A Review of Redolent Rush

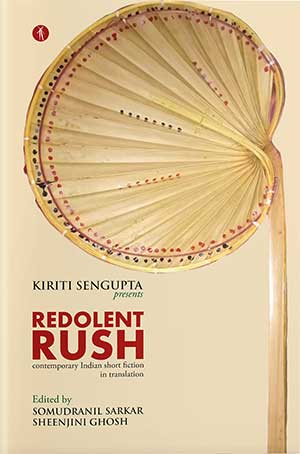

In Redolent Rush, a recent short fiction collection published by Hawakal, based in New Delhi, India, we have nineteen short stories by Indian authors collected for the purpose of documenting “things that hold our culture in bits and pieces,” as quoted from the inspiring introduction by editors Somudranil Sarkar and Sheenjini Ghosh. On translation they write, “The vulnerability of syntax of any language should be scrutinized before letting the vessel transform into a language—which the mind has not designed in the original version.” After the editors offer this thought-provoking statement on translation, they elaborate on why the volume is translated into English from several of the 780 languages spoken in India: “English should not be seen as a setter of a hegemonistic bar, but here in Redolent Rush, it serves as a vessel to gain a more comprehensive understanding and comprehensibility.” The purpose of the volume is clearly presented. Each story’s notes elaborate on specific cultural contexts, making such a vision precise. Readers also discover social and political problems of contemporary India that not only reflect long historical dynamics but the universal human drama, also introducing interpersonal complexity.

In Redolent Rush, a recent short fiction collection published by Hawakal, based in New Delhi, India, we have nineteen short stories by Indian authors collected for the purpose of documenting “things that hold our culture in bits and pieces,” as quoted from the inspiring introduction by editors Somudranil Sarkar and Sheenjini Ghosh. On translation they write, “The vulnerability of syntax of any language should be scrutinized before letting the vessel transform into a language—which the mind has not designed in the original version.” After the editors offer this thought-provoking statement on translation, they elaborate on why the volume is translated into English from several of the 780 languages spoken in India: “English should not be seen as a setter of a hegemonistic bar, but here in Redolent Rush, it serves as a vessel to gain a more comprehensive understanding and comprehensibility.” The purpose of the volume is clearly presented. Each story’s notes elaborate on specific cultural contexts, making such a vision precise. Readers also discover social and political problems of contemporary India that not only reflect long historical dynamics but the universal human drama, also introducing interpersonal complexity.

One may ask: what could an antiquated art tell us about the contemporary world, and why offer a translated volume in such a medium? A debate continues over the elite nature of English in India. Elite languages in India unite the linguistically diverse subcontinent, but many Indians perceive English from a class-based angle. Sanskrit and Persian were once such languages; however, English recalls the recent power relations of the colonial empire. The line drawn by the editors presents a pacifistic view of English amidst the ongoing debate. These stories are intended for readers and scholars to gain “considerable insight into what is being documented by contemporary short story writers in India,” in the words of noted poet and translator Kiriti Sengupta in the preamble. By presenting the stories in the world’s most spoken language while keeping cultural motifs intact, the editors showcase the evolving complexities of the Indian social world without overly politicizing the language.

By presenting the stories in the world’s most spoken language while keeping cultural motifs intact, the editors showcase the evolving complexities of the Indian social world without overly politicizing the language.

One example of the complications of rapidly evolving times is presented in Bitan Chakraborty’s “Landmark,” in which a man from Kolkata traveling to Delhi is lost and cannot locate the usual landmark that shows him to his friend’s home. When he arrives, his phone battery has died, and he is left in the cab confused about how to map his way to the destination. Since his last visit, the entire nature of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, has changed to reflect the Hindu majority. He notes that the city of Ghaziabad’s townships are cleaner and their scenery is “more refined.” While searching for the landmark meat shops, he talks with a shopkeeper and learns the government has banned meat. Consequentially, the entire city has undergone restructuring. The narrator reveals that at least forty meat shops were shut down locally and that beef must be procured from Delhi to be sold behind lamb illegally. This situation is common in the rapidly evolving modern world, but its specific symbolism underlies the cultural complexity of a changing India. In 2017 Uttar Pradesh’s government banned abattoirs and unauthorized meat shops; earlier this year, it also banned the open sale of meat along routes fixed for the Kanwar Yatra, an annual pilgrimage devoted to the Hindu god, Lord Shiva. These prohibitions reflect the surge of Hindu nationalism in India’s government and economically harm the poor.

The stories in this collection offer readers universal yet sometimes strangely unfamiliar situations. For instance, we find a bereaved son, Amiruddi, in West Bengal among characters in the story “Abbajaan’s Bones,” by Debabrata Choudhury. This character finds himself in the unique position of selling his father’s body to a skeleton market after documentation proving his citizenship is lost. In this tale, the author presents us with the mixed emotions of the worried son who views his birth as devalued. The symbolism presented by the story is socially relevant to India. Many of the anatomical models used by the world’s medical students come from Kolkata’s skeleton market, and the 200-year-long history of bone trading in Kolkata has left graveyards empty. In “Teen Choukke (Three Fours),” by Veena Vij Udit, the universal theme of grief is also illuminated through the tale of a mother’s loss. The mother, Pam, loses her daughter to a car accident in San Francisco. Pam is met with the strange coincidence of time: the exact time she learns of the death is 4:44. Later, a newborn infant is brought into the world at the same time, and Pam finds hope in the birth, as if witnessing the rebirth of her daughter. This tale, translated from Hindi, takes place in the United States among Indians affected by a kind of culture shock; the author writes that every doctor can be a multimillionaire, because in the US, “every citizen has to be medically insured.” In the story, this group often overcompensates for their foreignness (spending more on food to appear superior, for instance).

The meaning of citizenship in these two stories is brought into question from different angles, further elaborating the theme suggested in the introduction. In “Abbajaan’s Bones,” the bones of Amiruddi’s father signify his presence as a citizen indirectly, yet he is being robbed of them to enable proof of his citizenship to the authorities. In order to pay for documentation to prove his citizenship, he is forced to let go of his father’s body at the border. “The foreigner issue had been a trending topic for quite some time now,” the author writes. This story is poetically rendered from the Bengali, even among Amiruddi’s curses against his own father: “. . . why didn’t you, for once, think of the consequences before pouring heat into a woman’s body?” Even if Amiruddi is not a likable character for several reasons besides this expression of ingratitude, the reader is likely to pity him, unsure of whether he is experiencing grief or helplessness, perhaps both. This story portrays the collapse of Amiruddi’s identity as he comes face-to-face with mortality.

Popular fiction writer Khalid Hussain is represented as well, with “The Story of a Dead Man,” a piece on the problems faced by a gentle family man when meeting with violent insurgents near Kashmir. The Islamic insurgents know the man and his family, but he does not know them. This mysterious and frightening encounter reveals volumes about the nature of this type of violence. A man merely struggling to live on a border opens the door for “travelers,” revealing his gentle, and perhaps naïve, nature. As the story moves in just a few pages, he joins the violent men against his will. He becomes angry at authorities who fail to protect his well-being. This theme, which sheds light on government incompetence to protect civil life in such predicaments, also highlights the problem of terroristic violence generally. The story offers differing perspectives; for instance, one of the fighters says, “We are Mujahids, the brave hearts fighting against the Indian state. We are fighting a battle against the Indian Army and Police for your freedom.” The jihadists are able to speak for themselves, but the narrative tells of their actions more than their own words do. As the man joins the jihadists for his own complex motives, he is eventually killed by them. “I will go to those very terrorists because of whom, everything we once had has been reduced to a heap of ashes. No one can erase the bad name they have branded us with,” he confesses. The strangest enigma of the story is unveiled at the final plot point.

Short stories enable readers to engage with disagreement in a fundamental way: through dialogue and uncertain circumstances.

It is difficult to empathize with differing points of view, especially those with which we disagree. Short stories enable readers to engage with disagreement in a fundamental way: through dialogue and uncertain circumstances. “The Connubial Cyclone,” by Karra Nagalakshmri, presents several points of view balanced by Sujata, a grandmother whose son is facing the prospect of divorce. This story renders both generational and cultural differences clearly and simply. The story opens with the invitation of dialogue, but Sujata tells her husband the couple is too busy for her to approach the subject. Readers are not clear yet on what the subject may be, but as the story unfolds the difficulties her daughter-in-law and son face are brought into focus. Nagalakshmri’s narrative is true to life, presented by a singular view. We are informed about the fickleness of contemporary couples, and the presence of the elder Sujanta offers hope and reconciliation through a contrast between generations. “They attach rather excessive importance to their job but not to their family life,” Sujata reflects. Even the grandchildren are shown in their struggle through this narrative. Readers are inspired to wonder what might happen to Sujata’s youngest grandson, who is worried about his prospects during the ordeal. This story enables readers to examine the fragility of human institutions especially under the pressure of globalization. The grandson is concerned about being trapped in a welfare center pending the couple’s divorce. Sujata’s husband exclaims, “When Varun insisted on marrying that Tamil girl; you, instead of counseling him against it, tried to persuade me into agreeing to it by parroting their words on the grounds that times had changed, and marriages should take place only according to the likes and dislikes of the boy and the girl.” As someone who witnessed his peer relocated, the grandson sees parallels in his own parents’ situation. The extreme differences between his perspective and his grandfather’s are distinct: the grandfather declares the root of the couple’s conflict to be differences between his Indian son and his son’s Sri Lankan wife, while the grandson does not recognize such a distinction. His fear and concern is rooted in a sense of helplessness during the family conflict. While we are granted insight into the emerging importance of social structures such as the welfare centers, we are also led toward the paradox that institutions intended to lift us up can rob us of dignity and independence. The grandson’s fears are resolved when his grandmother is able to help realign the couple’s values, so they remain together.

Another connubial tale is “Being God’s Wife,” by Nandini Sahu. This piece of memoir fiction embodies the need for simplicity in social life, especially marriage. The father is seen as godlike in his simplicity and compassion. “He lived the life of a saint,” Sahu writes, “he was innocent like a five-year-old child even when he was seventy-five.” She writes further, “He was rather childlike in his behavior but rigid like a mature adult.” An anecdote concerning payment to the goldsmith reveals the childlike trust the father has of others. This story also reveals faults within social systems, as the author notes that the Indian health care system focuses on physical, not such much on mental, health. India’s National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences records that the majority of Indians with mental health struggles do not seek treatment. The subject of mental health tends to be taboo, and there are not enough mental health workers to meet the demand for them.

These tales are not merely stories but serve as vehicles for social criticism. Foreign readers will gain insight into India’s complex sociopolitical dynamics as they encounter everyday realities of our modern world. The stories underline and emphasize problems within the globalizing culture through the lens of Indian writers. Each tale is poetically compromising, challenging, yet universally applicable. As my aforementioned examples indicate, questions concerning what it means to be a citizen, domestic partner, child in a stagnating economy, and immigrant to another country suggest what life may become in the not too distant future due to social fragmentation. As the introduction states, “Things that hold our culture in bits and pieces, should find a way to get documented.” As Kiriti Sengupta writes in the preamble, “Short stories help understand a country’s culture, socioeconomic and political grounds, and, most importantly, the prevailing oppression.” Each story in this complex volume is exemplary of this statement.

Houston