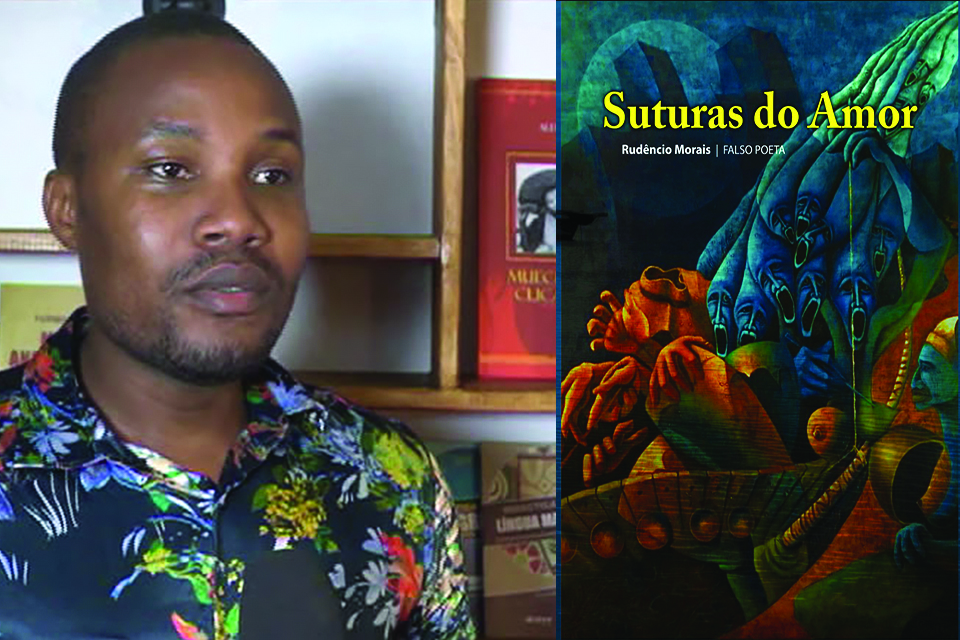

Rudêncio Morais: Suturas do Amor and the Beautiful, Persistent Threads of Pessoa

On the cover of his latest book of prose poems, Suturas do Amor (Editorial Autor, 2019), Mozambican author Rudêncio Morais announces that he is a poeta falso or “false poet.” In doing so, he alludes to the Portuguese poet/philosopher Fernando Pessoa and indicates that the work is a play of multiple masks, layers of play and dissembling, all constructed with a language that the poetics itself puts in doubt.

Pessoa built his work on the literary concept of the heteronym, an imaginary character created by a writer in order to write in different styles. It is both a literary device and a philosophical point of departure, as it problematizes the concept of author/identity and subverts the supposed intentionality of the meaning-making process. In the introduction, a stanza of Fernando Pessoa’s powerful and influential poem “Autopsychography” appears:

The poet feigns;

He feigns so completely

That the pain he feigns

Is the pain he really feels

In this stanza, Pessoa captures the essence of what it means to assume a persona or a complete identity in order to enter into a transcendental state of profound unity in order to produce art. The immersion into an identity is done in order to create an artifice that both stands on its own and is the mechanism for creating more art.

The “heteronym” or “false poet” allows one to transform words so that they can represent more states of being and can capture moments that illuminate the materiality of knowledge and human passion. Pessoa used the approach for his poems and prose poems. William Butler Yeats also used it when exploring the power of mythical and historical figures, particularly those of vexed, conflicted characters such as Cuchulain of Ireland. Yeats referred to the moment of assuming a different identity as writing from within a mask. Yeats, like Pessoa, also explored automatic writing (in The Vision) as a way to become one with the hidden, occult nature of reality.

In Suturas do Amor, the heteronyms are unnamed and unidentified, thus becoming a part of a hidden realm, a realm of secrets not only of subject but of origin and the nature of authorship.

In Suturas do Amor, the heteronyms are unnamed and unidentified, thus becoming a part of a hidden realm, a realm of secrets not only of subject but of origin and the nature of authorship. There are deep truths, and they tend to be transcendent or even mystical. After all, such mysteries of faith, knowledge, and experience rely on looking within and finding the “hidden inwardness.” Here Morais invokes not only Pessoa and Yeats but also Kierkegaard’s philosophy of subjective truths.

Knowing that we are supposed to read the poems in Suturas do Amor as automatic writing produced while channeling an assumed, invented persona manipulates the reader and further problematizes the meaning-making process, especially as it has to do with the relationships between the lover and the beloved.

In Suturas, prose poems stitch together, with very fragile threads, the moments of contact between people, the suturing together of experience, the senses of loss and longing, and, finally, rupture. The language is rhythmic and forms great structures of sound and repetition, resulting in a powerful and at times disconcertingly intimate set of poetic experiences. In “Weak,” the narrator describes how memories invade him. It’s a vertiginous concept: the invented heteronym, a persona that is then invaded by and deconstructed by another immaterial materiality.

In Suturas, prose poems stitch together, with very fragile threads, the moments of contact between people, the suturing together of experience, the senses of loss and longing, and, finally, rupture.

The words are material, and the prose poems become like Auguste Rodin’s sculptures, particularly “The Kiss,” and the frieze that depicts Dante’s Inferno and the gates to the Inferno. At the same time, the poems are intensely physical and visual, and they make one think of Egon Schiele’s structural intersections of bodies, buildings, colors, and forms.

While Morais does not clearly differentiate the masks or heteronyms that inform his prose poems, they do have different voices, which makes the collection a polyphonous stream of voices, almost a fugue with variations on the overall theme of love, which in Morais is almost an inversion of love or at least a commingling of love and loss.

In “I’ll Leave,” the moment of union and of transcendent joy is, in reality, unbearable, and a separation must take place. The moment of announcing one will leave triggers the longing for love and connection, so perhaps it is that painful cycle of self-imposed self-abandonment followed by searching for love that animates life and provides consciousness. This is the embodiment of the “myth of eternal return” that plays out in many of the poems.

In “Segredos,” the narrator describes always returning to the lake where they first swam together, but then the loss, and then the exhausting quest for another love. The secrets are the glue that holds the cycle in place; the knowledge that repetition of searching, finding, then abandoning is ultimately the embodiment of a kind of existentialist existence.

The joys of life, along with the harrowing losses, are ultimately self-directed. They live in the mind, even as the mind forms meaning around the cloth, rocks, water, and trees of the phenomenal world. For that reason, the ultimate experience is that of a resigned sort of lonely solitude.

University of Oklahoma

Editorial note: Dr. Nash also reviewed Morais’s verse collection Os dialetos do Amor for WLT.