The Bété Imaginary of Azo Vauguy

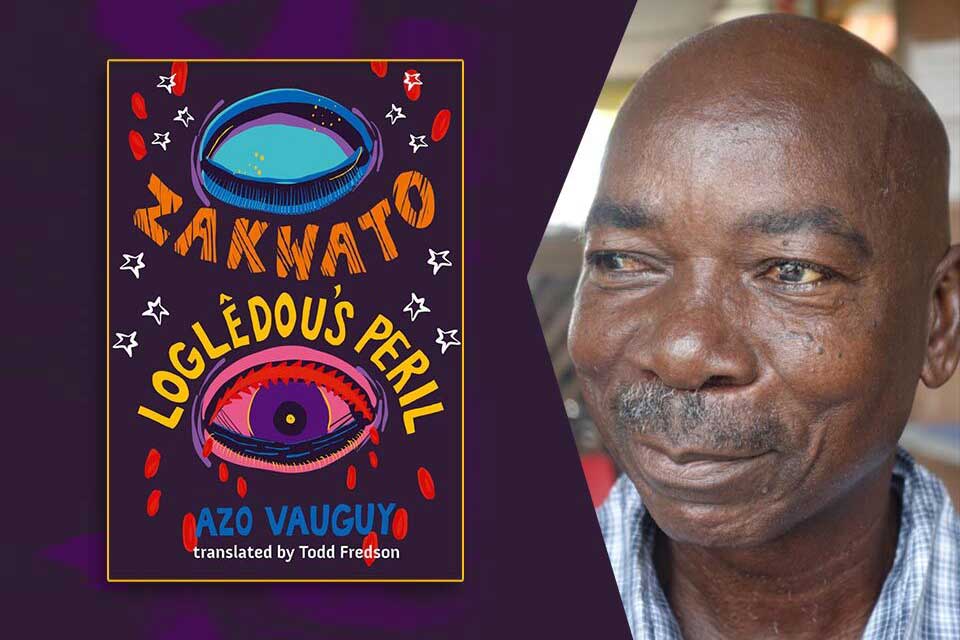

Todd Fredson’s translations of francophone African, specifically Ivorian, poetic voices over the past decade mark an important contribution to postcolonial and African studies, not to mention cultural studies and translation studies, rendering these works accessible to a broad audience of potential readers (see WLT, Jan. 2022, 19). Fredson’s recent translation of Azo Vauguy’s epic poems, Zakwato & Loglêdou’s Peril (Action Books, 2023), marks a momentous occasion for accessing the popular imagination of Ivorian poetry, and particularly the Bété imaginary that seeps through the language, infusing the original French—and Fredson’s English translations—with Bété words, rhythms, and tonalities. Zakwato, originally published in French in 2009 by Vallesse Éditions, and Péril Loglêdou, which first appeared in French in 2016 from Les Éditions Matrice, are significant poetic productions in and of themselves, particularly in how each speaks to the political and cultural turmoil of the early twenty-first century in Côte d’Ivoire, and together they reveal a trajectory toward reconciliation and a bright future that takes into account the weightiness of the past.

Todd Fredson’s translations of francophone African, specifically Ivorian, poetic voices over the past decade mark an important contribution to postcolonial and African studies, not to mention cultural studies and translation studies, rendering these works accessible to a broad audience of potential readers (see WLT, Jan. 2022, 19). Fredson’s recent translation of Azo Vauguy’s epic poems, Zakwato & Loglêdou’s Peril (Action Books, 2023), marks a momentous occasion for accessing the popular imagination of Ivorian poetry, and particularly the Bété imaginary that seeps through the language, infusing the original French—and Fredson’s English translations—with Bété words, rhythms, and tonalities. Zakwato, originally published in French in 2009 by Vallesse Éditions, and Péril Loglêdou, which first appeared in French in 2016 from Les Éditions Matrice, are significant poetic productions in and of themselves, particularly in how each speaks to the political and cultural turmoil of the early twenty-first century in Côte d’Ivoire, and together they reveal a trajectory toward reconciliation and a bright future that takes into account the weightiness of the past.

The political context mentioned above (discussed in detail by Fredson in the preface, “Translator’s Note: Idiom and Territory”) is immediately subsumed in the mythological universe that allegorizes the moment of loss and feelings of exclusion. Depicted with apocalyptic energies, the linked collections recall the initial traumas of colonialism as well as the postcolonial aftershocks that assumed the form of political-ethnic conflicts: “The city of honest souls was snuffed, sundered entirely under the violence and brutality of evil forces,” Vauguy begins in Zakwato.

Both texts are firmly rooted in the Bété imaginary’s inherent relationship to ancestral lands. The speaker invokes and appeals to the land of “Éburnie.” It is a name once proposed by a Bété revolutionary as an alternative to Côte d’Ivoire during early challenges to an autocratic regime that emerged after independence from French colonial rule. Vauguy’s distinction creates a distance between indigenous lands and the political construct of the modern nation-state that is referenced in the title of the second collection of poems: Loglêdou literally means “the land of elephants’ tusks” in Bété, referring to the French colonial designation, Côte d’Ivoire, or the Ivory Coast, which sat alongside the Gold Coast (Ghana) and the Slave Coast (Togo and Benin).

Vauguy creates a distance between indigenous lands and the political construct of the modern nation-state.

The long title of the first set of poetic expressions, Zakwato, so that my Land never sleeps again, is written more in the form of narrative poetry (or prose poetry, one might argue) with brief lyric interjections throughout. The attachment to the land is abundantly clear, but this land also assumes a metaphysical quality as the hero Zakwato almost immediately finds himself at the Ibo River, which, like the river Styx in Greek mythology, is a “Mysterious water that connects two worlds, those of the living and the dead.” The reader at once sinks into the rich Bété universe. And the reader sinks deeper into the human subconscious as Zakwato confronts the eternal temporality of life and death; their dimensions weave through one another. Zakwato’s journey emphasizes the deep spiritual significance attached to the land and its inhabitants. Physical and spiritual elements are often simultaneously represented in a name, such as “child-thing,” Zagréguéhia, which is a palm grain, or Zizimani, “man-with-the-eyes-of-a-serpent,” among countless others. Fredson’s careful attention to these cultural entities and their functions within the poetic epic brings Zakwato’s universe, which “men’s frivolities have buried … in the abyss of the forgotten,” back to life in ways that Vauguy himself intended, giving voice (and text) to cultural values wedded to territorial distinctions, a union threatened by the legacies of colonialism.

As Zakwato pursues his epic journey to remove his eyelids so as to never again fall asleep and allow the land of Éburnie—and by extension the Africa he envisions—to be perpetually endangered, caught “in the grip of the bulimia of 77-headed dragons,” he marshals all the powers of existence, calling on ancestors and the land’s spiritual dimensions. He invokes “the breath of the ancestor Gnènègbe,” which allows him to shapeshift into a giant bird so as to traverse the tall mountain range in his path in a single step. After many trials, tribulations, and transformations, our hero succeeds in reaching the distant forger to have his eyelids removed. And in so doing, much like the Greek mythic hero Orpheus, Zakwato transgresses the boundary between life and death, opening up a space for “the living and the dead together!” in which “death will expire!” This defeat of death by Zakwato marks a renaissance, not only for Éburnie but, as the poem insists, for the whole of Africa, which, like Zakwato, “tore away its eyelids and will sleep no more.” The vibrant, imagistic language of this epic poem appeals to the visceral senses as well as the transcendental experience, a tension that Fredson’s translation expertly captures.

The vibrant, imagistic language of this epic poem appeals to the visceral senses as well as the transcendental experience, a tension that Fredson’s translation expertly captures.

The second collection, Loglêdou’s Peril, Journey through the country of lost sight, which appeared six years after the first, might at first appear as an ironic juxtaposition given the resounding triumph heralded at the end of Zakwato. Yet we are led to understand that the blindness of the country referred to is the result of a much larger process: “The altars of African memory / Broken / Disarticulated,” which the poet further punctuates by repeating “Alas.” It would appear that Loglêdou, and the Africa envisioned by Vauguy—which includes Nubia, Zaire, and other regions of the continent explicitly—are suffering from amnesia. The land has lost itself to violence. Yet just as Zakwato is able to overcome the obstacles as he claims his identity in the first book, here in the second, Zakwato, who is often synonymous with the speaker, engages the spiritual dimensions, producing magic speech that shines a light in this darkness. Loglêdou is perilously balanced on a precipice of hope by the inherent power of the poetic voice and word: “My Word / Is / A matrix charged / to purify those souls stranded out there in line.” The word as weapon is the metaphor deployed here by Azo Vauguy, and Fredson’s translation of the rhythmic verse of this second collection, as well as the poetic prose of the first section, bears testament to the powerful incantatory qualities of the oral forms from which Vauguy draws. This verbal art form infuses the collective consciousness with desire and a drive to persist in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

Fredson’s translation bears testament to the powerful incantatory qualities of the oral forms from which Vauguy draws.

In spite of the pervasive darkness that infuses the poetic text, the word that animates and breathes life into the myth is rendered accessible to all readers through the poet’s invocation: “I am Zakwato / My name is multiplied.” It is precisely in the multiplication of words and their meanings that Fredson’s translations of Vauguy’s innovative wordplay, indigenous mythologies, and subtle cultural context-cues mark a watershed moment for West African poetry writ large. The combined translations of Zakwato and Loglêdou’s Peril are representative of a much larger corpus of African poetry whose words can be multiplied through translation to render their voices—and the many messages that they convey—intelligible to a broader English-speaking public. One hopes that such common ground is not so elusive, that Zakwato’s struggles and Vauguy’s tenor, now revealed to us via this translation, indeed have the power to move readers into a new light.

Arizona State University

Editorial note: Zakwato & Loglêdou’s Peril is a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle’s 2023 Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize.