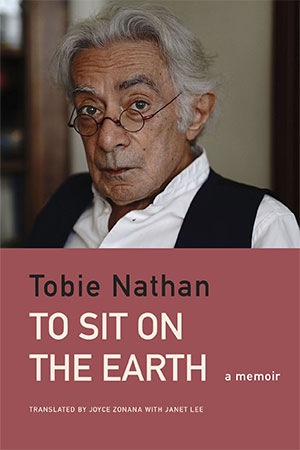

To Sit on the Earth: A Memoir by Tobie Nathan

London. Seagull Books. 2024. 303 pages.

Just as A Land Like You, Tobie Nathan’s novel, celebrates the fusion of Muslim and Jewish cultures in pre-Nasser Egypt, so his new memoir traces his path to ethno-psychiatry, which melds traditional non-Western healing modes and modern Western psychological theories into a powerful tool for easing mental pain in an increasingly heterogeneous global community.

Nathan’s first words, “In truth, I was born after my birth,” pose a riddle that the memoir answers. Born in 1948 in Cairo’s Jewish enclave, Nathan with his family fled Nasser’s anti-Semitism for France in 1958. Immersed as a child in Muslim and Jewish lore and mysticism, he wakes to the outer world in an impoverished immigrant Paris banlieue, his new home. Here he discovers Marx, Freud, and revolution and by 1968 helps lead the student uprisings, meeting with others to talk revolution, study Derrida, Lacan, Deleuze, et al., explore sex, and conduct “mutual analyses” of himself and others. These passages bristle with the energy of young minds lured by the ideal of freedom.

Finding college a daily diet of platitudes, Nathan flounders until he meets George Devereux, the “father of ethno-psychiatry.” Devereux becomes his mentor, Nathan his successor. With a thesis on London sex communities (where he finds that freedom brought only jealousy and anger), Nathan begins treating patients, lecturing, and visiting remote outposts in postcolonial cultures, until at thirty-one he accepts an invitation to open an ethno-psychiatric clinic in another Parisian immigrant neighborhood, Bobigny. His powerful results expand the field and bring his work respect.

These “facts” comprise disparate tesserae, embedded within an intricate spiral mosaic whose form mirrors its content: the wedding of binaries to embody the vastness of human consciousness and spirituality. The memoir contains twelve “chapters,” within which Nathan dashes back and forth in time, space, and psychic worlds. Each creates a distinctive design; woven together, deepening one another, they capture the essence of his unique journey.

Consider chapter 2, “To Sit on the Earth.” Nathan first recalls his Cairo childhood, wherein his family and community spoke Arabic—until Egypt, then hoping to “be European,” chose French. Says Nathan, “The Jews of Egypt, with their twice-millennial presence in that land, did not realize that their choice of the French language sealed their inevitable expulsion.”

Suddenly—a space, a break, the heading “October 1956, the Suez Crisis,” and the memory that while the Jews were terrified, Nathan loved the refined Arabic of the radio voices. Another space, a bigger break, a new heading, “L’Étang-Salé Les Hauts, 1996,” and now italics, generally used to relate Nathan’s travels outside the West. On Réunion, he seeks out Malabari, Malgache, and Creole spiritualists, who incarnate “the Egypt of my childhood.” When he treks to a distant cane field, the man he hopes to meet declares, “You’re finally here. . . . I’ve been waiting so long for you.” (In these visits, healers frequently anticipate his unannounced arrival.) Ordered inside, Nathan is warned he cannot leave until he recites a prayer. Crawling into the tiny hut, he searches hard until recalling random words from an old Jewish prayer about “joy, feasts for the times of happiness . . .”

The paragraph (still italicized) after the ellipsis recounts another meeting on Réunion with the greatly revered Visnelda, who becomes Nathan’s friend. On weekdays, she works in the mayor’s office, but weekends find her treating patients gratis in a dance hall. She “induces trances by throwing salt,” asks spirits “why they were inside her patients,” and invites Nathan to conduct an exorcism. New to his practice, he declines.

Three more stars, a break, italics gone: Nathan returns to Paris, where the “Deleuzes . . . Lyotards, Sartre, and Camus” have joined the student rebellion. In that “glorious summer of 1968,” he discovers Nietzsche and sanctioned sexual freedom. But by its end, after Russian tanks invade Czechoslovakia, he sees that the promise of revolution has brought only “the desire for merchandise and the freedom to consume.” Despairing, Nathan audits a class with Devereux and becomes an acolyte.

The penultimate chapter, “Prudence” (no italics), showcases the fruit of Nathan’s learning. In 1979, within his new ethno-psychiatric clinic, he deploys both Western and non-Western traditions to free Cameroonian Prudence from her burden. He lays his hands on hers, her breathing grows faster, her head shakes violently, her eyes startle open, and a deep male voice issues from her chest: her dead and buried stepfather. The family repaired, Prudence cured, the stepfather appeased, long gone, Nathan ponders “the distance that separates an ethnologist from the other worlds he manages to study.”

This tour de force, translated with rigor and love by Joyce Zonana and Janet Lee, ingeniously portrays a man whose odyssey allows him to contain and draw on the wisdom of many worlds, always with the goal of healing pain.

Michele Levy

North Carolina A&T State University