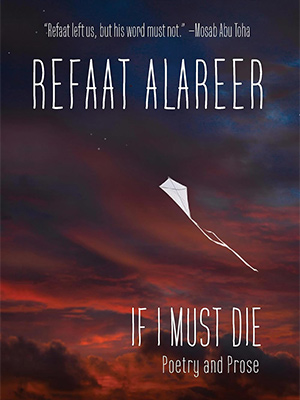

If I Must Die: Poetry and Prose by Refaat Alareer

New York. OR Books. 2024. 288 pages.

Poet, writer, teacher, academic, editor, activist, human being, Palestinian, Gazan—Refaat Alareer (September 23, 1979–December 6, 2023) was and remains a beacon of light in our darkened world. In his 2024 volume If I Must Die, the reader will find a tome of prose and verse that is as versatile as it is urgent. While the poems take up less space in the book, all plainspoken verses that are also heartrending, the prose, from 2010–2023, works in different forms and registers. We have interviews (both of and by Alareer), essays, lectures, pieces of memoir, and other kinds of creative nonfiction, articles, and, especially toward the end, covering the approaching time of his murder and beyond, more diary-like entries.

Satire opens the volume. Indeed, in the Gazan or Palestinian world, where even using the term “Palestinian” can be made a crime by the occupiers (“Israel Bombed My Home Without Warning”), and where one can speak of one’s child as being not, say, “two years old” but only as it were, “two wars old” (“Gaza Mourns Vittorio Arrigoni”), it’s no wonder that there is a place for irony in Dr. Alareer’s writings as much as there is a place for the more serious-minded reportage and illumination of the Israeli genocide, then as now, that takes up the majority of the volume.

Early on in “Israel’s Power of the Camera: Gaza’s Power of Gaza,” the satirical verve behind lines like, “That the majority of Gaza people live on a dollar a day is a viciously fabricated lie” or, below, “The Israeli hermetic seal imposed on the Strip for the past four years is not a siege. It is self-defense . . .” read like highly emotive refractions of rage. Or indeed, in “Tragedy in One Sentence”—the experimental gambit of writing about Gazan horrors in one very prolonged sentence—we have another, more formal instance of ironizing the truth at hand. These early, clearly emotive moves and moods in the book, artifacts no doubt of deep frustration and rage, soon move on to more straightlaced reporting and testimony.

As the eponymous 2011 poem “If I Must Die, Let It Be a Tale”—a poem that has gained notoriety as a symbol of the Palestinian resistance since then and to this very day—has it, the main tenor to emerge from this urgent record is about the vital role that writing and narrative can have in a time of abjectness, affliction, and horror. In his lecture “An Introduction to Poetry,” Alareer seems adamant to refute (if only implicitly) the famous W. H. Auden phrase, from his elegy to Yeats, that “poetry makes nothing happen.” Alareer makes use of fellow Palestinian poets Dareen Tatour and Fadwa Tuqan to argue that poetry can be a mode of resilience and survival and, indeed, of palpable hope.

By the following year, as reflected in his essay “Gaza Asks: When Shall This Pass?”, Alareer writes: “The wounds Israel inflicted on the hearts of Palestinians are not irreparable,” thereby indicating a salvaging role for writing. Still, in that same piece, he can say of the oft-repeated phrase on the lips of Israel’s victims, “It shall pass,” that sometimes he believes it and sometimes not. Though his fighting spirit enlivens each page of this book, his tenderness, vulnerability, and his honesty do so, too.

If this collection is to represent something more than an epitaph, it is exemplary in its display of the power of writing to forge continuity and community out of discontinuity, rupture, and death. This was in part—we learn from Alareer’s friend, colleague, and writer of the foreword to this volume, Susan Abulhawa—the reason Alareer chose to become an academic in English literature, writing in English: namely, to come to grips with the language of empire and thereby hope to deflate and disrupt the ambitions of empire.

Whether it’s the storytelling of others, putting human faces to the objective reportage of not only the thirteen years of writings collated in this volume but the seventy-seven or so years of occupation; recording his mother’s penchant for storytelling and then, later, his own habits of telling stories to his children; or, indeed, whether he is narrating personal experience—in all these facets, life is given again to life. Just so, the 2014 entry, “Narrating Palestine,” anticipates some of the notes, mentioned already above, from his 2021 introductory lecture to poetry. While adverting to his academic work with young Palestinian writers, ending in Alareer’s editing and publishing their works, in Gaza Writes Back (2014), this essay also encompasses much of the purpose of Alareer’s indefatigable practice in the wake of sheer horror.

“If Israel’s apartheid has to be fought, Israel’s narratives have to be challenged, and exposed.” Indeed, at one point in the second half of the book, we are reminded that Zionism originated via narrative vision before any particular physical or material conquest or theft. And this, too, I suppose, proves an analogue to the way Zionist Israel attacks the humanity of Palestinians, not only economically or infrastructurally, not only physically, but also at the level of spirit. Fighting back, in writing or otherwise, is thus a pivotal way to keep the spirit itself alive. At one point, speaking of a young nineteen-year-old, Ahmed Sheikh Khalil, in the 2018 piece “Haunted by the Horrors of Cast Lead,” Alareer notes how the young Khalil, once intending to be a medical doctor, decides that he could help his people “in other ways.” He went into media and journalism, we then learn.

And whether looking backward or forward, writing for Alareer was both a practice and a symbol of hope. In “The Story of My Brother, Martyr Mohammed Alareer” (2014), Alareer writes, in deep commemoration:

Israel’s barbarity to murder people in Gaza and to sever the connections between people and people, and between people and land, and between people and memories, will never succeed. I lost my brother physically, but the connection with him will remain forever and ever.

And yet, just preceding, in “Narrating Palestine,” narrative is implicitly held up as a bearer of futurity as much as a bearer of memory and connection to the past. “I want my children to plan, rather than worry about, their future,” Alareer writes, “and to draw beaches or fields of blue skies and a sun in the corner, not warships, pillars of smoke, warplanes, and guns.” In closing this piece, Refaat Alareer reinvokes his hopes for the stories by younger Palestinian writers that he curated in Gaza Writes Back.

Omar Sabbagh is a widely published poet, writer, and critic. His latest book, Gazan Days, was published by Dar Nelson in June 2025. He teaches literature and creative writing at the Lebanese American University (LAU).

Omar Sabbagh is a widely published poet, writer, and critic. His latest book, Gazan Days, was published by Dar Nelson in June 2025. He teaches literature and creative writing at the Lebanese American University (LAU).