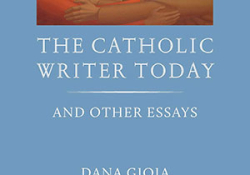

Poetry as Enchantment: And Other Essays by Dana Gioia

Philadelphia. Paul Dry Books. 2024. 272 pages.

Dana Gioia, one of America’s best living poets, also a critic and former chairman of the NEA, has gathered seventeen essays into his new book, Poetry as Enchantment. Like T. S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens, poets who also wrote essays about poetry, Gioia has the authority and clarity of someone proven successful in the art about which he is writing. His style, though erudite, is clear and without pretense, refreshingly free of theoretical and abstruse language and a great pleasure to read.

The lead essay, also titled “Poetry as Enchantment,” essentially continues to answer the question that Gioia first posed in another famous essay published in 1991, “Can Poetry Matter?” Comprised of seven sections, this latest essay develops the titular notion that poetry should enchant the reader—or the listener, rather—with its sound because poetry is first and foremost an auditory art. Gioia writes that “poetry predates history,” “is a universal human art,” and “originated as a form of vocal music.” The musical qualities of poetry are themselves inherent qualities of language, which are then cultivated or intensified by the poet. In English-language poetry, these enchanting sonic qualities traditionally include rhythm and rhyme (though not necessarily end-rhyme), specifically achieved by accentual-syllabic patterns as well as assonance and consonance.

“All poetic techniques exist to enchant,” Gioia states, “to create a mild trance state in the listener or reader in order to heighten attention, relax emotional defenses, and rouse our full psyche, so that we hear and respond to the language more deeply and intensely.” Poetry engages us more fully and, in fact, differently than the conceptual and abstract language found in textbooks and critical writing. He further writes that “poetry offers a way of understanding and expressing existence that is fundamentally different from conceptual thought.” Throughout this brilliant essay, Gioia continues to develop these and other aspects of poetry’s enchantment, also delighting the reader with pertinent facts and brilliant quotations. This piece alone is worth the price of the book, but Gioia is just getting started.

We then encounter a series of biographical portraits, sometimes of well-known authors such as Elizabeth Bishop, Philip Larkin, W. H. Auden, and Weldon Kees, but other times of lesser-known authors such as John Allan Wyeth, Samuel Menashe, and Shirley Geok-lin Lim. These essays are replete with literary insights and literary connections. Discreet details are sometimes the consequence of in-depth research that goes beyond the research of others, but often they are the consequence of Gioia’s personal interactions with the authors being discussed. Gioia was, for example, a student of both Donald Davie and Elizabeth Bishop and had multiple personal interactions with each.

The book then concludes with two opinion essays. The penultimate essay is a defense of Los Angeles as a cultural center. Gioia grew up in a working-class neighborhood of LA but later in life found himself in the cultural and economic corridors of the northeastern United States where Los Angeles was often derided or discounted as a city of cultural inconsequence. Gioia spent time at Harvard as a student but later also as a vice president of marketing for General Foods in New York. Those experiences along with his time in DC as chairman of the NEA make Gioia uniquely qualified to speak for “both coasts.” His defense of LA is high-spirited and sometimes humorous. This reader is certainly convinced by it (see WLT, July 2023, 12).

The final short essay, “The State of Poetry,” finds promise for the future of poetry in the current alternative ways that poetry thrives beyond print culture and academe. Gioia focuses on performed poetry in live readings or readings on television, radio, or the internet. He finds hope in this new auditory culture of poetry as well as in what he calls the “New Bohemia” comprised of “the legions of young writers, artists, musicians, and scholars who met with disappointment in the academic job market,” a constricted teaching market that simply cannot accommodate all the graduates of art programs. Instead, these “new bohemians” find their ways into the general culture and influence and contribute to it in ways unforeseen and good for the arts. “Together they have created a vigorous alternative culture that has broken the university’s monopoly on poetry. They have diversified, democratized, and localized American poetry.”

With this assessment, Gioia ends on a forward-looking and hopeful note for the enchanting art of poetry.

Fred Dings

University of South Carolina