6 Questions for Patrícia Melo

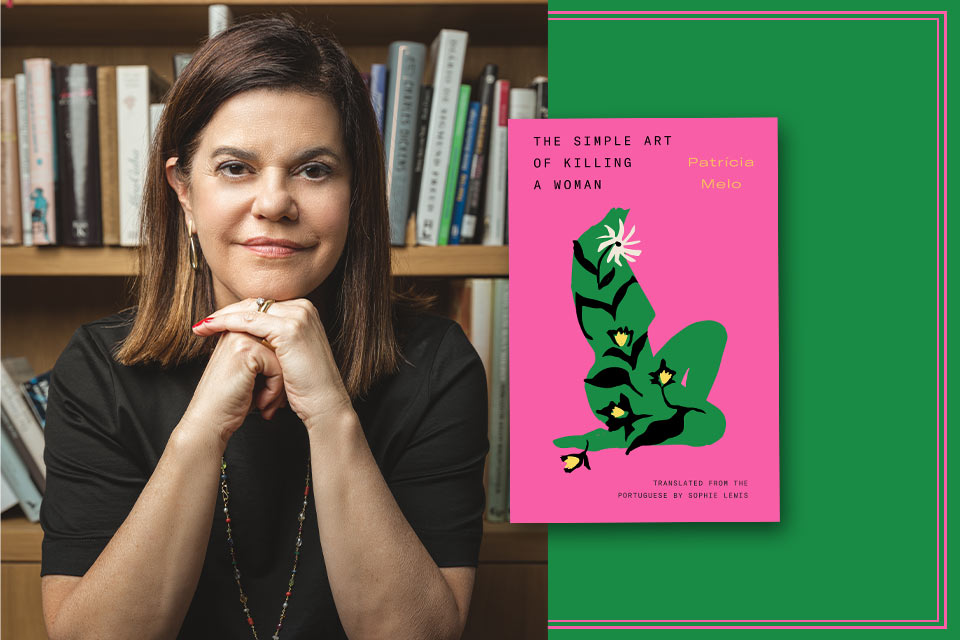

Brazilian crime-writer Patrícia Melo has a new novel available in English, translated from the Portuguese by Sophie Lewis. The Simple Art of Killing a Woman takes on femicide in Brazil, a justice system plagued by inequities, and even deforestation in the Amazon.

Brazilian crime-writer Patrícia Melo has a new novel available in English, translated from the Portuguese by Sophie Lewis. The Simple Art of Killing a Woman takes on femicide in Brazil, a justice system plagued by inequities, and even deforestation in the Amazon.

Q

The Simple Art of Killing a Woman is different than many crime novels and films, where the details of the crime can too easily dehumanize the victim. In your novel, the abundance of concrete details of the crimes against many Brazilian women creates a humanizing litany that illustrates how these crimes happen and how little justice there is for the victims. How did you arrive at this way of telling the story?

A

It’s common in literature that sometimes form is the by-product of content. That is the case in my novel. At a certain point during the creation of the book, I realized that I had fantastical and mythological material that was just as powerful and voluminous as the material gathered through research, and that I needed a more complex narrative. So I created a tripartite structure:

1. The first narrative refers to the story of a young lawyer from São Paulo who accepts an assignment in Acre, a state in the extreme west of Brazil with almost 80 percent of its area covered by the Amazon forest, to observe a task force created by the Brazilian judicial system to speed up the trials of femicide cases, the data from which will be used for an academic study about violence against women. There, while following the trials, she becomes involved in the investigation of the murder of an Indigenous teenager, Txupira, savagely raped by three young playboys, heirs of wealthy local families.

2. The second part is composed of actual crimes that I read about in newspapers during my research. They are presented like bizarre poems and also as examples of the atrocities the protagonist witnesses in the trials she attends.

3. The third part is about the world in which the protagonist seeks healing for her torn soul: the Amazon forest. Her visits to Acre are also spiritual journeys. During the rituals of an Indigenous community, guided by a shaman, she drinks ayahuasca, a mystical beverage for self-knowledge, and, in a dreamlike narrative, she becomes a member of an imaginary group of Amazon warriors who fight for justice for women.

Q

You’ve written several novels, but this is your first from a female protagonist’s perspective, a challenge from your editors that you embraced. Why is this your first, and how did that change impact your writing?

A

I guess I could say that my previous novels are attempts to understand the Brazilian reality, which is deeply shaped by violence. Violence is a structural part of our culture: State violence. Violence from drug traffickers. Militia violence. Violence caused by social inequality. Violence from the patriarcado. In this context, the protagonist is always a man. In this novel, I wanted to have women as protagonists, women not only as victims (in Brazil, four women are murdered every day, victims of femicide) but also as an incredible force of resistance in a traditionally patriarchal state.

Q

The special section in this issue focuses on Writing the Polycrisis, with a special emphasis on climate lit. What is the state of the climate crisis in Brazil, and how are activists responding?

A

Today my son called me from Rio de Janeiro, saying that the city reached almost 50℃. This is new. Shamans from the Amazon have been drawing our attention to the climate tragedy for much longer than scientists. These shamans are like the birds that sing at dawn in the forest, bringing news of what is to come. The problem is that the authorities don’t listen to the shamans or to the scientists. Until the end of 2022, under the disastrous government of the extreme right, the Amazon forest was plundered in every way possible and imaginable. Lula’s government has already managed to reduce deforestation considerably. Unfortunately, this is not enough.

Q

Do you see a connection between high rates of femicide and threats to the environment?

A

I believe that violence against the Amazon forest has the same roots as the violence against women’s bodies. Both are body-destroying violences allowed by society. I don’t think it is possible to understand the climate issue and the destruction of the Amazon forest without understanding the policy of destroying bodies that is currently in force in society.

Q

Which crime writers have influenced you the most?

A

I think I’m past the age of being influenced by other authors. At sixty-one, I already have my own voice, my own way of telling my stories. But I learn from other authors. Every reading is a learning opportunity. I’m currently reading The Iliad for the first time, in Emily Wilson’s magnificent translation. It’s very inspiring.

Q

What cultural trends currently have your attention?

A

I feel like a bird out of the nest with this question. I live a solitary life here in Switzerland. Here I have my husband, my books, my lake, and my craft. That’s what moves me and feeds me.

Patrícia Melo (b. 1962) is a highly regarded novelist, playwright, and scriptwriter. She has been awarded a number of internationally renowned prizes, including the Jabuti Prize (2001), the German LiBeraturpreis (2013), and the German Crime Award (1998 and 2014). She was shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, and Time magazine included her among the Fifty Latin American Leaders of the New Millennium.