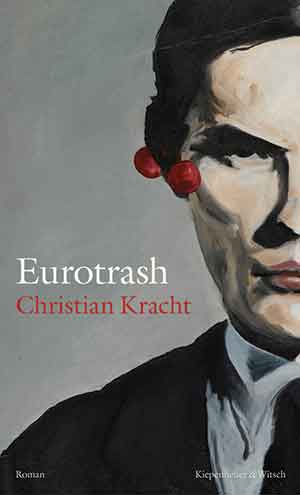

Eurotrash by Christian Kracht

Cologne. Kiepenheuer & Witsch. 2021. 224 pages.

Cologne. Kiepenheuer & Witsch. 2021. 224 pages.

CHRISTIAN KRACHT’S EUROTRASH features the same narrator from his 1995 debut novel, Faserland, and in fact begins where the previous novel ends—in Zurich. As in the earlier work, a road trip provides the story’s framework, but this time around the self-absorbed protagonist has a companion—his alcohol- and prescription-drug-addled mother, who spent her eightieth birthday at a nearby clinic in the psychiatric ward. In keeping with genre conventions, the travelers must navigate situations at times serious and at times farcical while simultaneously exploring the contours of their own dysfunctional relationship. Yet whether they arrive anywhere new isn’t terribly important. It’s the trip that counts, and Kracht ensures that readers of Eurotrash will go on a twisted trip of their own.

Although mother and son are Swiss and their travels are confined to Switzerland, the family’s origins are German; indeed, German history and family history are inextricably linked in Eurotrash. The narrator’s maternal grandfather, for example, had been an unrepentant Nazi, and, upon his death, the family discovered a secret stash of S&M devices as part of his fantasy involving young Icelandic women because they alone represented “the Nordic ideal.” In other passages, the narrator reminisces about his father’s postwar rise from rags to riches by way of close connections to controversial publisher Axel Springer.

Throughout the novel, these and other, more troubling memories surface in the narrator’s thoughts and spark brief consideration before then being tucked back into his unconscious. Without naming it explicitly, the narrator recognizes his family’s unprocessed, painful memories as rooted in transgenerational trauma and guilt: “Mir fehlte die Erklärung des größeren Zusammenhangs der Umstände meiner Familie. Es war, als lief[] ich jahrzehntelang am Rande enormer Bosheiten mit und könne sie nur nicht erkennen” (I lacked the bigger connections of my family’s circumstances. It was as though I had been running along the edge of vast malevolence for decades and just couldn’t see it).

While the road trip provides Eurotrash’s basic framework, it is in fact autofiction that drives the narrative. The first-person narrator is named Christian Kracht, and he self-identifies as the author of Faserland. His deceased father’s name is also Christian Kracht, just like the father of the author, and numerous episodes from the real Christian Kracht’s biography populate the narrator Kracht’s memories. As one reads along, the author-narrator Kracht makes it all but impossible not to question whether certain memories are “real” or imagined, thereby imbuing the fictive narrative mode with the autobiographical and inviting a second, more critical layer of reading. This second-level reading raises particularly unsettling questions about the relationship at the heart of the novel. To what extent is narrator-Kracht’s mother based on author-Kracht’s mother, including experiences of sexual abuse she suffered as a child, as well as the addiction and narcissism that define her as an older adult? Or is she purely fictitious, set in the story merely to embody his own feelings of inadequacy as a son and a writer?

While Kracht’s life no doubt shapes the story, the narrator is nonetheless unreliable—as was the case in Faserland—often admitting to memory lapses or by getting facts wrong, such as the title of David Bowie’s final album. Thus, while the text regularly suggests a certain autobiographical authenticity, it then undercuts its own veracity, leaving the reader to decide what to believe. An exchange between mother and son early in the journey exemplifies this dilemma and can stand emblematically for the entire novel. The mother says, “Erzähl mir doch etwas” (Tell me a story), to which her son asks, “Wahrheit oder Fiktion?” (Truth or fiction?). The mother answers, “Das ist mir egal. Entscheide du” (It doesn’t matter. You decide).

Jason Williamson

University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee