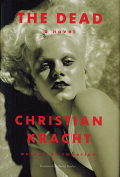

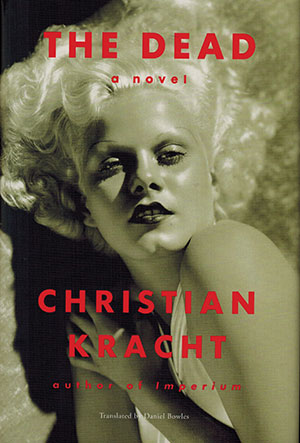

The Dead by Christian Kracht

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2018. 195 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2018. 195 pages.

Our hero, the no-longer-young Swiss director Emil Nägeli, with thus far one cutting-edge film to his credit, finds himself, his natively sober judgment loosened by liquor, entering a “Faustian pact”: he will go to Japan to inject German cinematic panache into that country’s film efforts. He makes this pact with Alfred Hugenberg, then head of the German film conglomerate UFA, who would shortly turn it over to the Nazi Party as he became its new government’s minister of economics.

Christian Kracht has situated us on the very brink of the Nazi dictatorship. In the last gasps of the Weimar Republic, Nägeli’s summons to Berlin came just in time for him to meet the prominent film critics Siegfried Kracauer and Lotte Eisner, who are shortly afterward on the midnight train to Paris. Hugenberg makes sure Nägeli understands that these two are hardly part of his Nordic set—of which we meet leading German actor Heinz Rühmann and man-about-town Putzi Hanfstaengl—though he also observes later that he was not about to sacrifice a true German on this Japanese mission when a mere Swiss would suffice.

The mission is to form a “celluloid axis” between Germany and Japan to beat back the burgeoning dominance of American film. As in the original Faustian deal, there are higher powers and purposes behind these machinations: the project has been engineered by top strategists of Japanese statecraft who mean to channel German cinematic acumen to achieve their country’s imperial pan-Asian ambitions.

History, we know, turned out otherwise, but Nägeli makes the best of his initially unsuccessful sojourn in Japan, using his new cameras to explore remote and exotic aspects of the country. The footage he brings back, titled the same as this book, gets the attention of Swiss journalists, one of whom lauds the director as “avant-garde and surrealist” (another finds “mentally deficient” more fitting). He is granted a guest professorship at his hometown university of Bern.

Knowing this bit of the plot will not spoil reading Kracht’s novel. Its pleasures lie elsewhere. They are not avant-garde, instead harkening back to the baroque with even the occasional rococo ornament in the book’s idiosyncratic style and luminous images. Unlike the films of that era, Kracht’s novel exposes the reader to a vast array of color, especially a surfeit of the bright reds of blood and of the ubiquitous Nazi flags signaling all too ominously this most tragically surreal moment in recent history.

All this has once again been masterfully translated by Daniel Bowles, who makes it easy to see that, unlike Nägeli’s perhaps sometimes-soporific one, a film of this novel would be brilliant indeed.

Ulf Zimmermann

Kennesaw State University